The levee breaks destroyed much of New Orleans: lost in the floodwaters were 200,000 houses, 81,000 businesses, 175 schools, and 6 major hospitals. But the high ground of the French Quarter—the original center of the city—was left mostly unscathed: destruction was manifest in visible, and survivable, elements like caved-in chimneys, uprooted oak trees in the courtyard of the St. Louis Cathedral, and blown-off roof tiles scattered through the neighborhood’s streets.

Hurricane Katrina seemed to have washed away their pasts—his tour in Iraq, her sexual abuse—and created a world of their own in which they could fall in love.

Because the French Quarter was in relatively good shape and Zack and Addie believed that they had endured the worst by remaining in the city during the storm itself, they refused to even consider evacuating New Orleans. Their decision to stay put pre-and post-Katrina put the couple in a tiny minority of the city’s residents. Those who had the means to evacuate before the storm did so and most of those who remained when the levees broke evacuated shortly afterward due to a lack of food and drinking water, an absence of electrical power, and homes that had taken on several feet of water.

Instead of evacuating a nearly emptied-out New Orleans, Zack and Addie happily embraced survivalism back at the Governor Nicholls apartment, fashioning paper plates into flyswatters and using tree limbs for campfires. During the day, Zack and Addie would clear Governor Nicholls Street of trash and felled tree limbs. When they completed their cleanup tasks in the late afternoon they’d down cocktails served on ice that Zack had stashed away from Hog’s Bar. At night, the couple would put a rickety white-painted wooden table and a few folding chairs on the street in front of their apartment and serve dinners of canned beans or canned soup to their fellow holdouts over an open bonfire—often started by lighting old mattresses.

When their dinner guests went home, Zack and Addie lit candles and listened to Trouble, the 2004 debut from singer-songwriter Ray LaMontagne, on a battery-powered boom box. Its title track quickly filled the soundtrack to their relationship. “I’ve been saved,” LaMontagne sings on the song’s chorus, “by a woman.” Yet Trouble also hinted at problems to come—the CD’s cover art features an illustration of a devil courting a young woman wearing a blindfold. In the early morning hours, when the French Quarter was completely quiet and still, Zack and Addie would make love right in the middle of the street.

The immediate aftermath of the levee breaks—mass power outages, eerily abandoned streets, and a silence that descended over the entire city even during the daytime hours—had a cleansing effect on Zack and Addie. The disaster seemed to have washed away their pasts—his tour in Iraq, her sexual abuse—and created a world of their own in which they could fall in love. On the rare occasions when Zack and Addie left the perimeter of the Governor Nicholls apartment, they biked down the French Quarter’s streets holding hands as they pedaled.

Zack and Addie were not alone in enjoying the survivalist life in the post-Katrina French Quarter. The near total lack of local, state, and federal government assistance to hurricane-battered New Orleanians was nearly as debilitating as the levee breaks. So those who remained in the city, particularly in the small, close-knit French Quarter—a neighborhood, ordinarily, of about four thousand permanent residents and many other visitors, where only a few dozen remained—banded together in order to survive.

“We didn’t see cops for about six days,” Jack Jones, one of the most prominent and well-prepared survivalists, remembers, “and when the cops would come by, they’d ask if we had weapons because they were being overrun.” A profound sense of unity and pride was forged from these ugly and desperate circumstances.

On September 4, 2005, the few who remained in the French Quarter were appropriately described as “tribes” by an Associated Press reporter. Indeed, the AP piece—“French Quarter Holdouts Create Survivor ‘Tribes’”—went on to describe how the neighborhood holdouts boasted of their ability to overcome the lack of essentials such as electricity and hot water, and of their pride in their fellow residents for tapping into the best of themselves when so many in the city appeared to be doing just the opposite. “Some people became animals,” one French Quarter resident told the AP while sipping a warm beer. “We became more civilized.”

Zack and Addie, unsurprisingly, were thrilled to participate in this refined brand of post-Katrina tribalism. Even before the storm, Addie had been searching for some kind of tribe of her own, and Zack had longed to rediscover the strong sense of brotherhood he had experienced with his fellow 527th MP Co. soldiers.

“It’s actually been kind of nice,” Zack told a reporter from the Mobile Register one morning as he stood on the sidewalk in front of the Governor Nicholls apartment, picking up felled tree limbs. “And I’m getting healthier, eating right and toning up.” Zack was equally enthusiastic when talking with his brother, Jed, who called one night to check on him from Iraq, where he was serving his first tour in Saddam Hussein’s hometown of Tikrit.

“Everything’s fine,” Zack told Jed. “We’re living the good life down here. I’ve got a camp stove and lots of cans of beans. And I broke into a bunch of bars and stole all the booze.” Zack sounded a similar note when talking with the Register. “We’re bartenders,” Zack said, “so we’re well stocked.”

When the couple ran out of booze, they would frequent the two French Quarter bars that remained open around-the-clock in the wake of the storm: Molly’s at the Market on Decatur Street and Johnny White’s Bar on Bourbon Street.

One night at Johnny White’s, Zack and Addie began chatting with bartender Greg Rogers, known by everyone as Squirrel. Squirrel had seen both Zack and Addie working at Hog’s Bar but had never been formally introduced to them. “I know you,” Squirrel told Addie that night. “I think your name starts with an A.” Addie shook Squirrel’s hand. “I’m Addie,” she said, and then introduced Zack. After a few rounds of drinks, the couple invited Squirrel back to the Governor Nicholls apartment for more cocktails, but he passed on the offer because he was working long shifts. Squirrel then told the couple that if they needed drugs—coke, pot, anything—he’d be happy to take care of them.

The next night, Squirrel ran into Zack and Addie on Royal Street and they said they’d like to take him up on his offer. But before Squirrel could hand them a twenty-dollar bag of coke, he got a call from a manager at Johnny White’s that he was needed back at the bar. So he suggested Zack and Addie follow him there. As they turned the corner onto Orleans Avenue, they were approached by a group of NOPD officers. And as the cops strode across the street toward the three of them, Squirrel inconspicuously dropped the bag of coke by the tire of a parked car. Zack flashed his military ID, Addie her driver’s license, and Squirrel said simply, “I’m a bartender,” which in the Katrina-wracked city put one on par with EMTs, firefighters, and even the Coast Guard, who had rescued or evacuated more than 33,500 people in Katrina’s aftermath. The cops let the whole group go. Before Squirrel split off from Zack and Addie, he gestured toward the bag of drugs on the ground, which the cops had failed to notice. When the NOPD left the scene, Zack discreetly picked up the bag of coke and he and Addie headed toward Governor Nicholls. The incident made Squirrel curious about his new friends. He was shocked that Zack—who since returning to New Orleans had let his hair grow out in a wild, blondish brown mane—had a military ID. And, as a veteran of the war in Afghanistan, in which he had served as a navy corpsman, Squirrel wondered whether Zack had ever been to war.

The kid-gloves treatment that Squirrel, Zack, and Addie received from the NOPD that night was a good example of the French Quarter holdouts’ semi-VIP status. Many of the holdouts, including Squirrel and Zack and Addie, even became momentary media celebrities, profiled by reporters in publications ranging from Time magazine to the Mobile Register to The New York Times. But it was a front-page New York Times piece—appropriately headlined “Holdouts on Dry Ground Say ‘Why Leave Now?’”—that brought the couple the most attention. The article described Addie’s dedication to keeping the spirit of the city alive even in the wake of the greatest disaster in its history:

In the French Quarter, Addie Hall and Zackery Bowen found an unusual way to make sure that police officers regularly patrolled their house. Ms. Hall, 28, a bartender, flashed her breasts at the police vehicles that passed by, ensuring a regular flow of traffic.

The Times piece was even approvingly linked by Manhattan media gossip website Gawker. “JOE FRANCIS,” proclaimed Gawker’s editors, referring to the Girls Gone Wild impresario, “WOULD BE SO PROUD.”

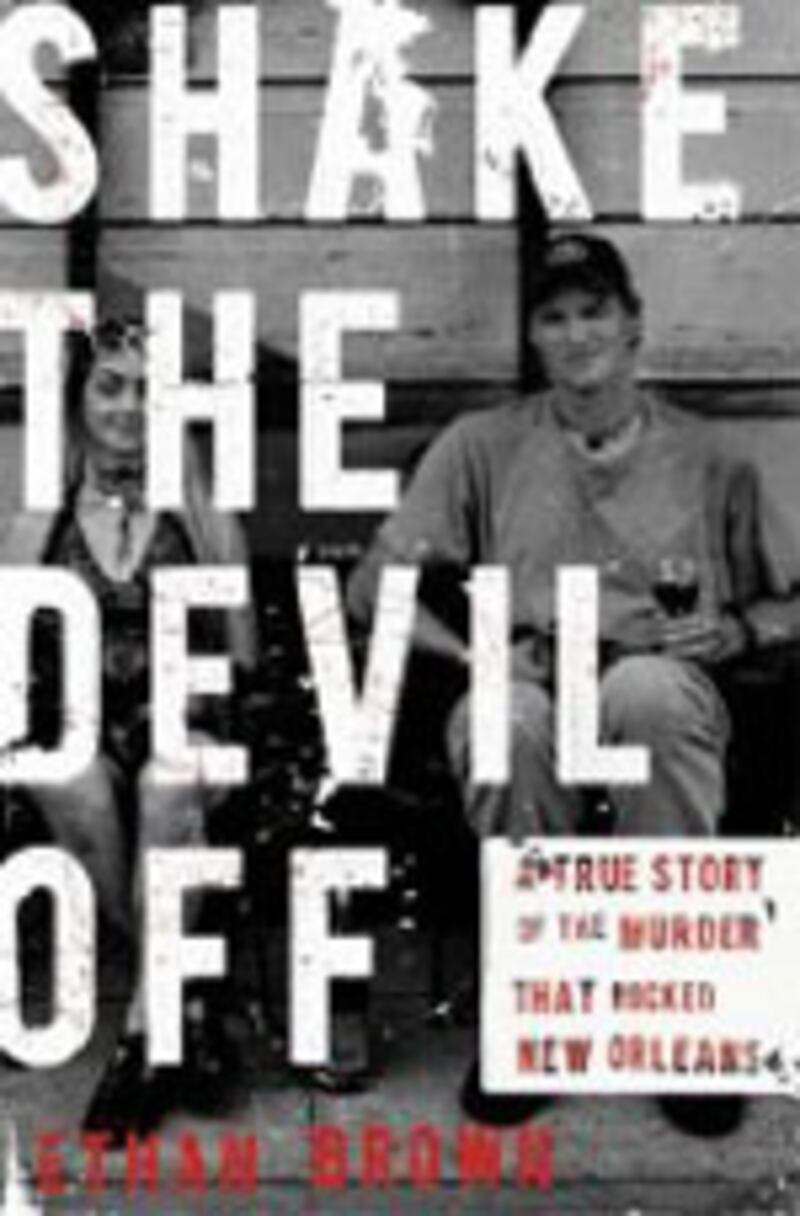

Adapted from Shake the Devil Off: A True Story of the Murder that Rocked New Orleans by Ethan Brown. © 2009. With permission from the publisher, Henry Holt and Co.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Ethan Brown has written for New York magazine, The New York Observer, Wired, Vibe, The Independent, GQ, Rolling Stone, Details, The Guardian, and The Village Voice, among other publications. He is the author of two previous books, Queens Reigns Supreme and Snitch. He lives with his wife in New Orleans.