BERLIN — Eighty years ago, on the night in which the Nazi regime’s marginalization of Germany’s Jewish minority turned to naked terror, Torah scrolls were burned in the Rykestrasse Synagogue in Berlin. Friday morning in the same synagogue, on a day that also marks the 100-year anniversary of the birth of the democracy that tolerated Adolf Hitler’s rise to power, German Chancellor Angela Merkel asked the question: “What have we really learned?”

To connect Germany’s present to its past is to provide a foundation for a future “in which we recognize a person in every person,” Merkel said. The Holocaust memorial at the center of Berlin tries to give meaning to the unbelievable number of six million murdered Jews by naming them individually. “It is about people,” Merkel said, “Every single one had a name, intrinsic dignity, and an identity.”

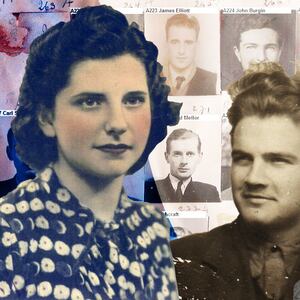

The brutality of “Kristallnacht,” or Crystal Night, as the Nazis called a night of broken windows and spirits, did not just play out in cities, but also reached far into the provinces. The violence also took place in Austria, which had been annexed by the Nazis to cheering crowds in Vienna a few months earlier. Not every region has confronted its past in the same way, and not many witnesses are still alive today. But we were able to speak to the Holocaust survivor Menachem Mayer, who was born in a small German village called Hoffenheim, and to Siegfried Kernberger, from the southern Austrian state of Carinthia, on what they remember of that night.

ADVERTISEMENT

In the very early morning on November 10, 1938, six-year-old Menachem Mayer stood shivering in pajamas on the sidewalk and watched uniformed thugs throw furniture out the window of the first floor of the synagogue, while his father, a cantor, hurried up the stairs to save some clothes and other belongings. A stormtrooper lieutenant had just come up the road and screamed at his men to burn the building down.

Menachem Mayer and his older brother Fred tried to avoid most of the kids in their neighborhood. Earlier that year, a group of boys ambushed Menachem on the side of the road, beat him up, and pushed him into a bunch of stinging nettles. Before that, some of the village kids tried to drown Fred in the river. “This was my world,“ says Menachem Mayer, who was born one year before Hitler was elected Germany’s chancellor. “I didn’t know it differently."

The day before the Mayer family were driven out of their home, 10-year-old Siegfried Kernberger stood in front of the primary school in an Austrian state called Carinthia and chanted, “One people, One leader!" It was the weekly afternoon meeting for the “rascals,” or, as they were called formally: German Youngsters of the Hitler Youth. Already, “Aryan” children like Kernberger were being sucked into the Nazi machine.

“The most talented Heil Hitler screamers already had their own uniforms,” Kernberger recalls, “but we were mainly loafing around at these rallies.” After a bit of marching, he asked his group leader and friend—a 14-year-old called Otto—if they could go home. But the boy pointed at a nearby bed of gravel instead and told the boys to go fill their pockets with rocks.

With stones in their pockets, Siegfried Kernberger and the other young boys filed past the town square—renamed “Adolf Hitler Platz.”

“Sharpen the long knives on the sidewalk,” Kernberger and his peers warbled, repeating after Otto and the other older kids at the front, “Jewish blood must flow.”

A few hours earlier, the Nazi delegation in Munich had received news that a German diplomat had been shot in Paris by a 17-year-old Jew, whose family were among the thousands of Poles in Germany who had been deported to the Polish border, where they were stuck, freezing and hungry.

For Hitler and his propaganda minister Josef Goebbels, this was an opportunity to order the stormtroopers to carry out a pogrom that foreign diplomats would later be assured was a “spontaneous outburst of anger“ by the German people, who certainly did very little to oppose it.

Footage of the night showed firefighters calmly keeping flames that engulfed one synagogue from spreading to other buildings, and spectators applauding from their balconies while the roof of another burning synagogue collapsed.

In the Carinthian town, the kids stopped in front of Julius Gruber’s convenience store. Julius Gruber was Jewish and he was popular with the town’s working-class families. He gave generously to the annual winter collection drive and was known to slip his customers an extra pair of socks or insoles when they bought a pair of shoes from him. Now the excited kids smashed his windows. Kernberger, who says he hid in the bushes nearby, heard them inside the house; breaking dishes and clanking on the piano. Then he heard Gruber’s wife and daughter screaming. “That’s when the penny dropped, that this should not be happening,“ Kernberger says.

Over the course of 24 hours, as many as 1,000 Jews were stabbed to death, shot, or committed suicide.

Menachem Mayer’s father was one of the 30,000 men between the age of 16 and 60 to be arrested and taken to a concentration camp. In Dachau, he shared barracks meant for 40 people with around 300 others. But this was before “the final solution.” A preamble. Karl Mayer returned home one month later. His head was shaven, he was desperately thin and wearing only one shoe.

Six-year-old Mayer asked his father if he’d brought back any chocolate. “My parents tried to protect us,” Mayer says. “They did not tell us about the things that were happening in our surroundings."

Menachem and Fred’s parents eventually were sent to Auschwitz, where they died, while their children survived.

Fred later found out that their parents had tried to escape from Germany. They were waiting for their turn with the American consulate when the Gestapo came to his family’s door and ordered them to pack for deportation to France. At this point the consulate had just gotten to visa application number 900,000. The Mayers’ number was 1,600,000. Karl Mayer opened his desk drawer to get out the silver cross medal that he had won fighting for Germany in World War I. He threw it at the German officers’ feet and shouted, “Is this what I fought for?”

Shortly after their shop was smashed and looted, Julius Gruber and his family fled to Venezuela. Siegfried Kernberger heard something once about Gruber’s daughter getting married. In Carinthia, where Kernberger still lives, he says, “Most of what I know is by word of mouth.” And there are those, like the former group leader, Otto, who spent the rest of their lives claiming not to remember anything. “I think he was ashamed,” Kernberger says. “It is easiest to just say: I don’t know.”

In fact, the conservative right has long established its own sort of “Gedächtniskultur" here—World War II veterans and their fans still meet on Ulrichsberg mountain once a year. Meanwhile, it took until 1999 for Carinthia to even put up a monument to citizens who were murdered by the Nazis. And once it was up, a group of young men, who spoke the familiar regional dialect and came from middle-class families who’d lived in Carinthia for generations, began to attend annual carnivals and church holidays with tools in their backpacks.

They’d come into the pub wearing button-down shirts and get wasted with everyone else—drinking games, or “kneipe,” as they call it—until it was dark outside and they felt audacious enough to stumble into the city center, where they used snow poles or rocks to break the glass plates that bore the Jewish names that Hitler and his henchmen, enabled by the apathy and resentments of the majority, had tried to eradicate. In a literal sense, Kristallnacht continued.

According to one local, before these fraternity boys were caught, “No one would have guessed that they were behind this.”

But the committee that had pushed for the monument was less surprised.

When a high-school teacher named Hans Haider first proposed to investigate and make public the names of Carinthia’s victims of National Socialism, it was if he’d kicked a hornet’s nest. Even the Social Democrats were hostile.

“They all thought it was an attack on them, that it was about settling scores or finding the guilty ones,“ says Robert Kravanja, a local businessman who helped fund the project. “We knew we would have to keep rebuilding the monument in glass until peace prevails against violence.”

He says the monument has not been damaged in the past decade, but there are still “diverging points of view.”