When it comes to losing weight, nothing works better than diet and exercise. But in the future, getting rid of excess poundage may be as simple as flipping a switch and adding a little novel chemistry.

A team of Korean researchers devised a technique that gets at the root of appetite: ghrelin, the hormone that causes you to feel hungry. In a new study published Wednesday in the American Chemical Society’s journal Applied Materials & Interfaces, the researchers created a stomach implant that releases a chemical compound—activated by light from a laser—that kills cells at the top of the stomach that produce ghrelin. The treatment may pave the way for a minimally invasive alternative to current surgical weight loss options like gastric bypass or gastric banding.

First discovered in 1999, ghrelin is primarily produced at the top of the stomach by a structure called the gastric fundus. When your stomach is empty and you haven’t eaten in a while, ghrelin is produced and released into the bloodstream where it travels to the brain and gets your appetite going. Once you’re full, the hormone dips down. (Ghrelin levels tend to skyrocket when people go on a diet, which could explain why dieting can be so hard.)

When it comes to targeting the hormone for weight loss, scientists and clinicians have developed everything from drugs that block ghrelin to surgeries that remove the gastric fundus entirely. But the drugs can have side effects (ghrelin is also important for mood and gut movement). Removal of the gastric fundus is permanent, invasive, and can lead to side effects like indigestion or malnutrition.

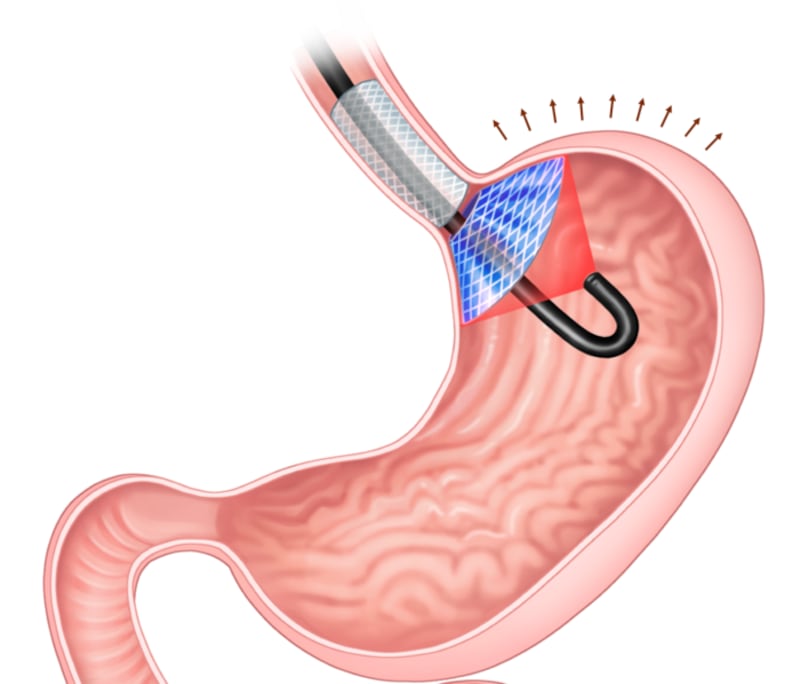

The implant (seen in blue and gray) creates a feeling of fullness by pressing on the stomach and, when activated by a laser (black), killing cells that produce the hunger hormone.

Adapted from ACS Applied Materials & InterfacesThe Korean researchers’ new implant is called an intragastric satiety-inducing device, or ISD. It’s inserted and anchored at the top of the stomach with the help of a mesh. The ISD itself is just a disk with a hole in the middle to allow food to pass through. But it’s coated in an FDA-approved drug called methylene blue that, when exposed to laser light, produces a chemically reactive form of oxygen that kills nearby ghrelin-producing cells and stops them from growing back as long as the ISD was exposed to the laser. The researchers tested out the device in trials on pigs and found that it could halve body weight gain after just one week of use.

Since the treatment is reversible and the ISD is easily removed, the researchers hope their device may be a viable option for patients in the future contemplating bariatric surgery. But as physiologically similar pigs are to us, the device still needs to undergo rigorous testing and clinical trials before it can cross over and solve human weight-loss woes.

It’s reassuring at least, that we’re not just stuck with exercise and having to diet.