A death penalty case now pending in Oklahoma raises an important question of judicial ethics and makes a federal appeals court judge look both sneaky and biased. The question is simple: What duty does an appellate judge have to disclose to the parties before him any definitive public statements he once made about the guilt of the defendant he’s subsequently been asked to judge? Put another way: What right does a capital defendant have to know that one of the jurists sitting in judgment upon him once declared to the world that he was guilty beyond all reasonable doubt?

The story starts in 2002 when Julius Jones, a black man, was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death for killing a wealthy white man in an apparent carjacking episode. Jones’s co-defendant, a man named Christopher Jordan, testified against him at trial. Jones, for his part, argued that Jordan was the shooter. After the trial, Jones’s lawyer, David McKenzie, decried the racial component of the trial, claiming there was no way his client could have received a fair trial free from bias or prejudice in the county.

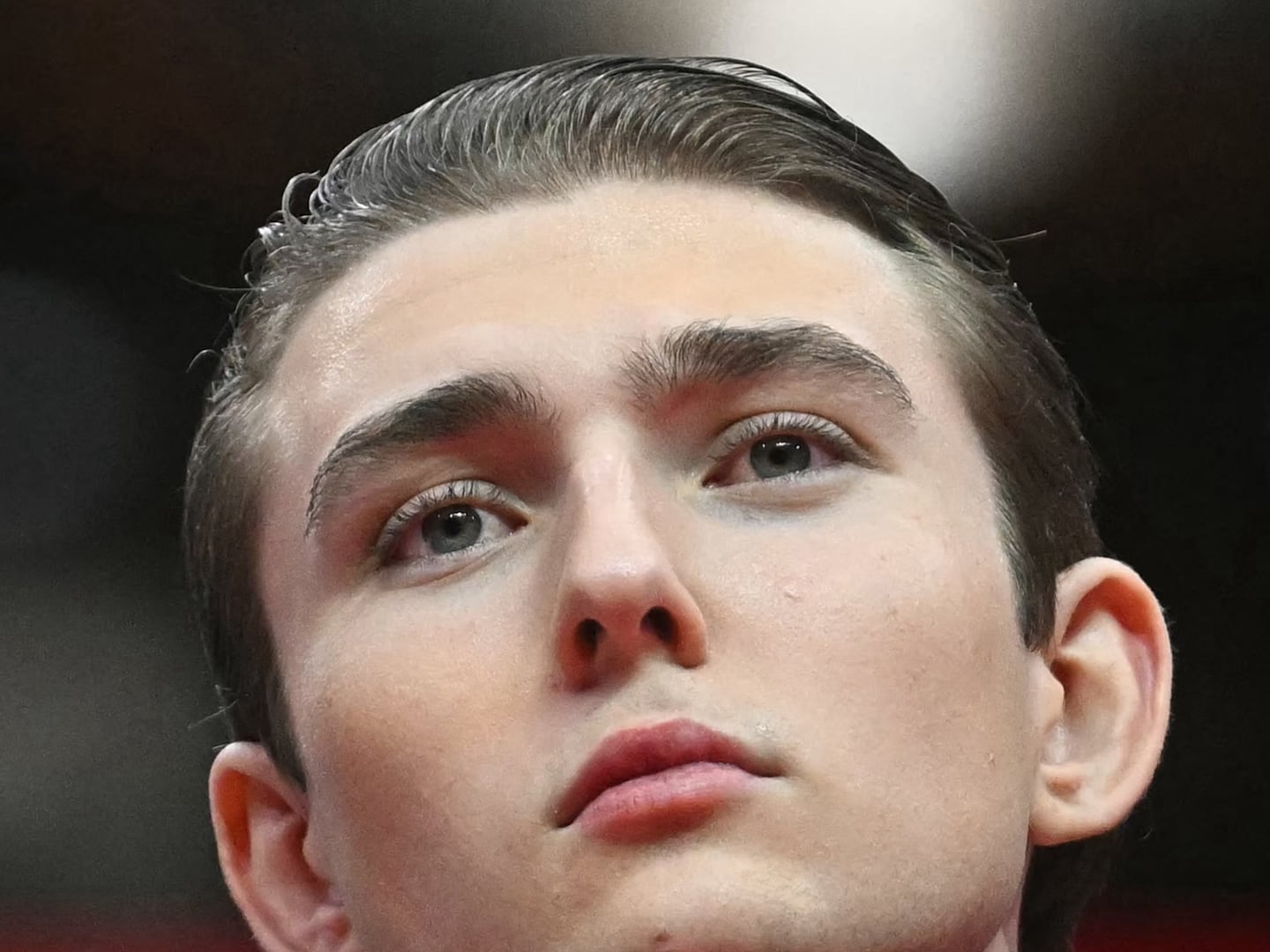

Coming to the defense of the trial judge, and of the conviction, was Jerome A. Holmes, then deputy criminal chief in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Oklahoma. Holmes, who also is black, wrote an opinion column piece in the Daily Oklahoman, the state’s largest newspaper, mocking McKenzie’s claims of racial bias in the Jones’s trial.

“[T]here was ample evidence for a rational jury to find that [Jones] gunned down an innocent stranger,” Holmes wrote, “and that Jones deserved to die for his acts.” Holmes then called out McKenzie, the lawyer, for making “factually unsupported claims of racial bias.” It is odd that Holmes, a federal prosecutor, wrote such a pointed piece—and was allowed to do so by his bosses.

Four years later, in part because of fiery missives like that one, , President George W. Bush appointed Holmes to the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, where he was confirmed after significant opposition by Democratic lawmakers, and where he has been ever since a staunch opponent of most civil rights issues. Nine years later, Jones’s case moved out of the state courts and found its way to the 10th Circuit, Judge Holmes’ court,. Jones’s attorneys claim that McKenzie, the trial lawyer, had rendered his client ineffective assistance of counsel by failing to investigate a lead that a witness had heard Jordan, the co-defendant, claim he, not Jones, had been the shooter all along and that Jordan had framed Jones.

When Jones’s current lawyers appealed this issue to the 10th Circuit they were randomly assigned a three- judge panel. They were told the identifies of the judges about a week before oral argument in the case and did not conduct an investigation into whether any of the three judges had any conflict of interest that would render their participation in the case a breach of their judicial ethics. And why would those lawyers conduct such an investigation? Judge Holmes had an affirmative duty to recuse himself from a case where his impartiality could be reasonably questioned.

Yet Judge Holmes did not recuse himself. Nor did he even alert the lawyers in the case that he had written that piece in 2002, which then would have allowed Jones’s lawyers to request the judge’s recusal. Instead, Judge Holmes sat silent until the oral argument, which lawyers say he “dominated,” and then ruled against Holmes (as did the other two judges who heard the case, the ruling was unanimous). It was only after this decision came out on December 5, 2014, that McKenzie, the original trial lawyer, noticed Judge Holmes’s involvement and alerted Jones’s current lawyers about the obvious conflict of interest.

Those lawyers last week filed a motion with the 10th Circuit requesting a rehearing of their case before a new panel of judges that does not include Judge Holmes. A federal judge has a duty to recuse himself, Jones’s lawyers told the Court, in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned or where “he has a personal bias or prejudice concerning a party, or personal knowledge of disputed evidentiary facts concerning the proceeding.” The court now has ordered the state’s attorney general to respond next week—although the problem has nothing to do with state prosecutors.

This is not a close case. At a minimum, a federal judge has an ethical duty, if not a legal one, to bring an evident conflict to the attention of the lawyers, which federal judges around the country do all the time. His failure to do this, alone, could arguably constitute the “bias” the law recognizes as a recusal reason. And, if not, the appearance of bias also merits recusal. The 10th Circuit should do the right thing and reassign the case to a new panel. Judge Holmes should be required to explain why he sat silent about that opinion of Jones while he was sitting in judgment of Jones.