Usually, I enjoy the release of my films—savor the reviews if they are good, and wince if they are not so good. Either way I am emotionally engaged and grateful if people talk about my work, whether to praise or criticize. The Last Mountain is entirely different. Whatever the critics say, and however it is received by the viewing public, it will always pain me to watch it. In fact, since completing the film I have never replayed it in its entirety—and may never do so again. Don’t get me wrong, I’m extremely proud of The Last Mountain, a film that took me over 25 years to complete. But it was not the story I set out to tell nor was it the story I wanted to tell. Sadly, it was the story I had to tell.

The film focuses on the death of 30-year-old British mountaineering genius Tom Ballard, a close friend I’d known for most of his young life. That’s why I had to alloy my instincts as a filmmaker—not only with my own personal sadness for his loss but my deep concern for Tom’s beloved sister Kate and devoted father Jim, also close friends.

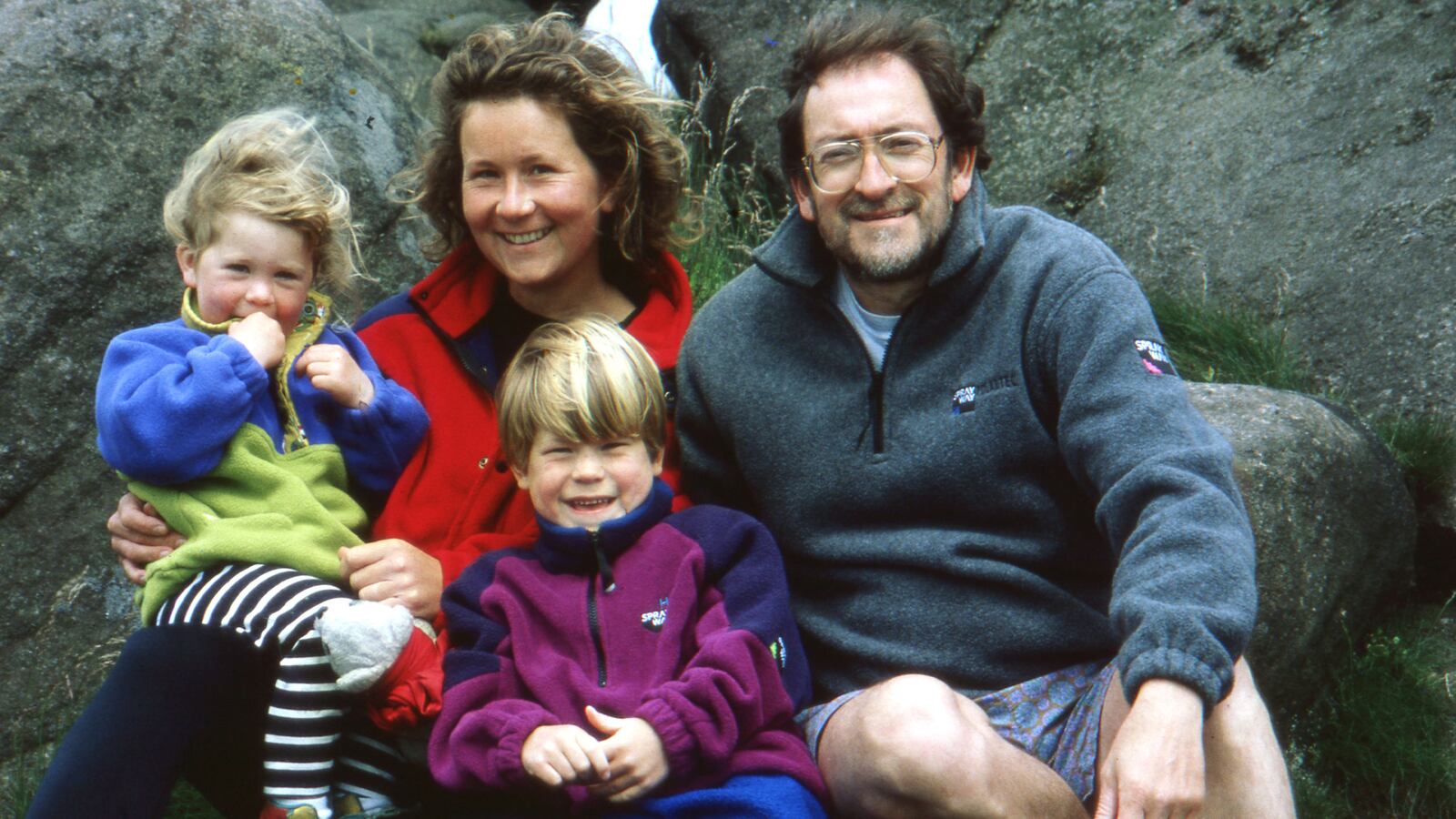

It was 1995 when I first met the extraordinary Ballard family. Tom was six and Kate only four. Jim was leading an expedition to take them to K2 in Pakistan, the world’s second highest mountain, and I went to film it for the BBC. It was not a climbing expedition but a pilgrimage to allow the children to say their final goodbyes to their mother, Alison Hargreaves, Britain’s greatest female mountaineer. A month after climbing Everest, the first woman to climb it solo and without supplementary oxygen, she summited K2, an unprecedented feat in one season. But on her descent, she was lost to a violent storm and her body never found, so there could be no conventional funeral to help the family heal.

Supported by 80 porters, one of whom carried Kate on his broad back, we trekked over some of the most rugged but majestic terrain on earth. Crossing glaciers and raging rivers, we made it to base camp where Tom and Kate built rock cairns in memory of their mum. It was an epic journey for two small children but if they achieved some sort of closure on one level, a deep-seated energy and passion was also ignited within them.

After making a film called Alison’s Last Mountain, I remained close to the family and watched (and continued to film) as Kate developed her own love affair with mountains as well as astonishing skiing and snowboarding skills. Tom grew into a powerful, personable young man with an innate climbing talent. It was in his DNA. It was his superpower. A Spider-Man made flesh, Tom never wavered in his desire to scale whatever was in front of him: Colossal granite boulders, sheer rock faces, vertiginous ice walls, and soaring mountain peaks. By his mid-twenties, Tom was one of the world’s most accomplished alpinists, but he never strayed from his mother’s climbing ethos—a firm set of beliefs that defined her relationship with mountains. Respecting their power, she never saw them as innately malevolent or as an enemy to be assaulted or conquered. And so it was with Tom. “You have to be as one with a mountain,” he insisted. “When I climb, I’m like a moving rock or a piece of ice and if the mountain tells me it doesn’t want to be climbed, I’ll go away and come back another day.”

Tom knew the risks. He knew that peril and jeopardy stalked him on the mountains. But for him, fear was a strength. He developed a spiritual appreciation of danger, and this defined his relationship with the peaks he attempted to summit. At the age of 16, I remember him telling me he had a “calling” to climb. I pushed him on this. “So, when you’re climbing you feel in touch with something deeper within you?”

“Very much so,” he replied. “But you don’t know what it is—it just feels right.”

Over the years I amassed more and more footage of Tom and Kate and planned to make another film about them, which I intended to call Children of the Mountains. It was a pure labor of love, and I could envision the fairy-tale ending: From an early age, Tom’s dream was to climb K2 himself and Kate always said she would accompany her brother to support him. This triumphant return to the mountain that cradled their mother would be the glorious culmination of our film, the heroic apogee of a story well-told. There was a redemptive poetry to this vision—a purifying catharsis. I could see it so clearly in my mind’s eye.

But in late February 2019, this reverie was shattered. Tom went missing on Nanga Parbat, a gigantic Himalayan peak barely 100 miles from K2. This was not in my fantasized script. Within a week, Tom and fellow climber Daniele Nardi’s bodies had been spotted on an inaccessible rock face high up on the mountain.

Suddenly, our prospective film had a tragic twist: The son had perished just as his mother did, and there was a stark symmetry to the tragedies even though 25 years separated them. Considered the finest climbers of their generation, Tom and Alison died at almost the same age, in the same mountain range, and in similar circumstances. Neither of their bodies were recovered so both lay encased in ice forever—each with a Himalayan mountain as their headstone.

When Tom was confirmed dead, Kate was left bereft. She tried to make sense of the twofold tragedy in her young life; to justify the risks taken by mother and brother. Part of her needed to celebrate their sacrifice, their courage, and their glorious achievements. But part of her wanted to blame them, too—blame them for sentencing her to a life of enduring grief and sorrow. How could she pull herself out of the terrible sense of hopelessness that engulfed her?

Wanting to be close to Tom, she elected to travel to Nanga Parbat—his own last mountain. Once again, I accompanied her as I’d done 25 years earlier on the trek to K2, her mom’s last mountain.

The journey, physically and psychologically demanding, was cathartic for Kate and filming it helped to focus her emotions too, but I never underestimated the emotional impact it was having on her and I tried not to be too intrusive. It helped that I do my own filming and sound recording so she was never surrounded by a crew.

Atop Kleines Schreckhorn, a mountain in the Bernese Alps

UniversalChildren of the Mountains, the film I started shooting 25 years ago as a labor of love, had been overtaken by events. Its successor, The Last Mountain, remained a labor of love but in a very different way. By exploring Tom’s hopes and dreams and probing the curious circumstances of his death, it asks the age-old question: What motivates people to climb mountains? What prompts them to pit their skill and strength against the invincibility of nature and the insuperability of gravity? Climbers are perplexing creatures, driven by imperatives most of us cannot begin to understand. Tom was such a creature—complex, determined and introspective, but always valiantly trying to extend the boundaries of human endurance.

He was made of the right stuff. He was made of his mother. But that did not make him invulnerable. Maybe for Tom the lure of the mountains was simply too strong to resist. Perhaps it was not so much a calling as a need to feed an addiction or even to play out a destiny beyond his control. Was there simply no escape from the elemental desire to commune with rock, ice, and snow? For him it was a life sentence willingly served but ultimately a death sentence, too.

Though as his father Jim observed, “Tom was a mountain warrior who died doing what he loved to do and who will be 30 years old—forever.”

The Last Mountain, a film I can no longer watch, might be a source of disquiet, inner turmoil and regret for me but, despite its inherent tragedy, the film does uplift and inspire thanks to the remarkable people that the Ballards are. I have to simply accept that real life does not keep to a preferred path or follow a predetermined script. Fact is often more nuanced than fiction, more dramatic than make-believe, and fairy-tale endings come in many guises.