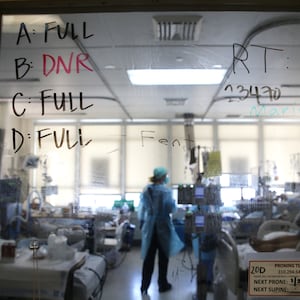

The fight against COVID seems to have fallen into a ping-ponging rhythm at this point, where every step forward seems undercut by one backward. Vaccines are available, and hospitalization rates have fallen dramatically from previous peaks. But just a sliver of eligible Americans have received the most recent bivalent shot, and the specter of a new, somehow worse variant looms large in our collective psyche. Elsewhere, such as in China, we seem to be losing ground to the virus: a less effective vaccine, paired with low vaccination rates, limited natural immunity, and discontent over a national Zero-COVID policy, may spell disaster in the coming weeks. But amid this impasse, scientists may have found a drug that will decisively shift the battle back toward humanity’s side. And the best part is, people have already been prescribed this drug for over 30 years.

Though they can be highly effective, our current methods of preventing and treating COVID-19 infections all suffer from a fatal flaw, said Teresa Brevini, a U.K. biologist who recently completed her Ph.D. at Cambridge University.

“Vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, and antivirals all act on the virus, and unfortunately, as we've seen, this virus is quite smart and it can mutate,” Brevini told The Daily Beast. She is the first author of a new study into ursodeoxycholic acid, or UDCA, to prevent COVID. Crucially, instead of acting on the virus, UDCA modifies human cells to block the virus from infecting them. “If we just shut the door on the virus, it really cannot do anything,” Brevini said.

Brevini and her colleagues’ research was published in the journal Nature on Monday.

UDCA “shuts the door” on COVID by decreasing the amount of a receptor called ACE2 on the surface of cells. ACE2 normally controls blood pressure and limits organ damage, but by a twist of fate, it also makes for the perfect docking station for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. When the virus infects the cells in a person’s respiratory tract, it uses ACE2 receptors like doorways.

In the early months of the pandemic, Brevini and her lab were working remotely during lockdown when they noticed a quirk in some of their liver cells.

“We were all at home, checking some of our data on the computer, and we said, ‘Hang on—ACE2, the door that the virus uses, is expressed in our cells,’” Brevini said. Not only that, the researchers had unintentionally increased the number of ACE2 receptors in some of their liver cells. Brevini said that the next scientific hypothesis came logically to her and her team: “If we have a way to increase how much receptor is present on the cell—so how susceptible the cells can be to the virus—maybe we can use the same mechanism to reduce the amount of the receptor.”

She and her co-authors started pulling on this thread, testing UDCA on cultured clusters of gallbladder, lung, and intestinal cells and determining that it lowered ACE2 levels in all three cell types. Subsequently infecting these masses of cells with SARS-CoV-2 significantly decreased the amount of viral genetic material compared to clumps that had not been given the drug. They repeated this experiment in mice and hamsters before moving to a pair of human lungs on a mechanical ventilator. This part, Brevini said, was “like Frankenstein.”

“You see the lungs outside the body, and there is a ventilator, and you see them inflating and deflating. My mind was blown seeing this experiment,” she said.

The researchers split the lungs in two and gave one lung UDCA while using the other as a control. After six hours, three areas in the treated lung had cells with fewer ACE2 receptors than in the untreated lung, and these regions were then less susceptible to viral infection.

Most experimental therapies take years of clinical study before they ever make it into a living human, but UDCA is already widely prescribed to treat cholestatic liver disease. By comparing COVID-19 infection data of chronic liver disease patients who either took UDCA or did not, Brevini and her colleagues were able to analyze the results of a natural experiment. They found UDCA patients had reduced odds of 46 percent of contracting COVID-19; when they did catch the virus, they were less likely to exhibit moderate, severe, or critical forms of the disease compared to liver disease patients not taking the drug.

Finally, eight healthy volunteers agreed to take UDCA in pill form for five days. Researchers measured ACE2 levels in their noses with daily nasopharyngeal swabs, finding reduced levels of the receptors even in a matter of days. Brevini said that this finding makes her hopeful that one day, the pill could be used as a way to lower one’s risk of picking up an infection, with or without an exposure.

“Say you have lunch with your coworker one day, and then the day after he texts being like, ‘I'm so sorry, I developed COVID,’” Brevini said. “If you have gotten your vaccine, you're protected from that point of view, but is there something more that you can do? We think you could preventively take this to reduce the chances of this particular virus to infect your cells.”

“It is remarkable that a safe and available drug” might be able to prevent COVID-19 infections, Stuart Lipton, a molecular medicine researcher at The Scripps Research Institute who was not involved in the study, told The Daily Beast in an email. “The drug certainly warrants further testing” in a randomized and forward-looking human clinical trial, he added.

Even so, Lipton cautioned that UDCA may come with unwanted side effects on humans’ blood pressure and kidney function, which can happen when the number of ACE2 receptors on a cell are decreased.

“I am concerned that widespread use of the drug might reveal severe and unwanted side effects, especially in vulnerable, elderly populations that would need drug treatment the most,” he said.

Other groups of researchers are working on ways to cut down on ACE2 receptors in just the cells that are vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection, in the respiratory tract and lungs. Lipton led a study that was published in Nature Chemical Biology in September and found that a targeted method of blocking off ACE2 decreased the virus’ ability to infect human cells and hamsters.

What these methods have in common is a promising tactic to fight this virus that we’ve had in our arsenal all along: slamming the doors to our cells and preventing infection in the first place.