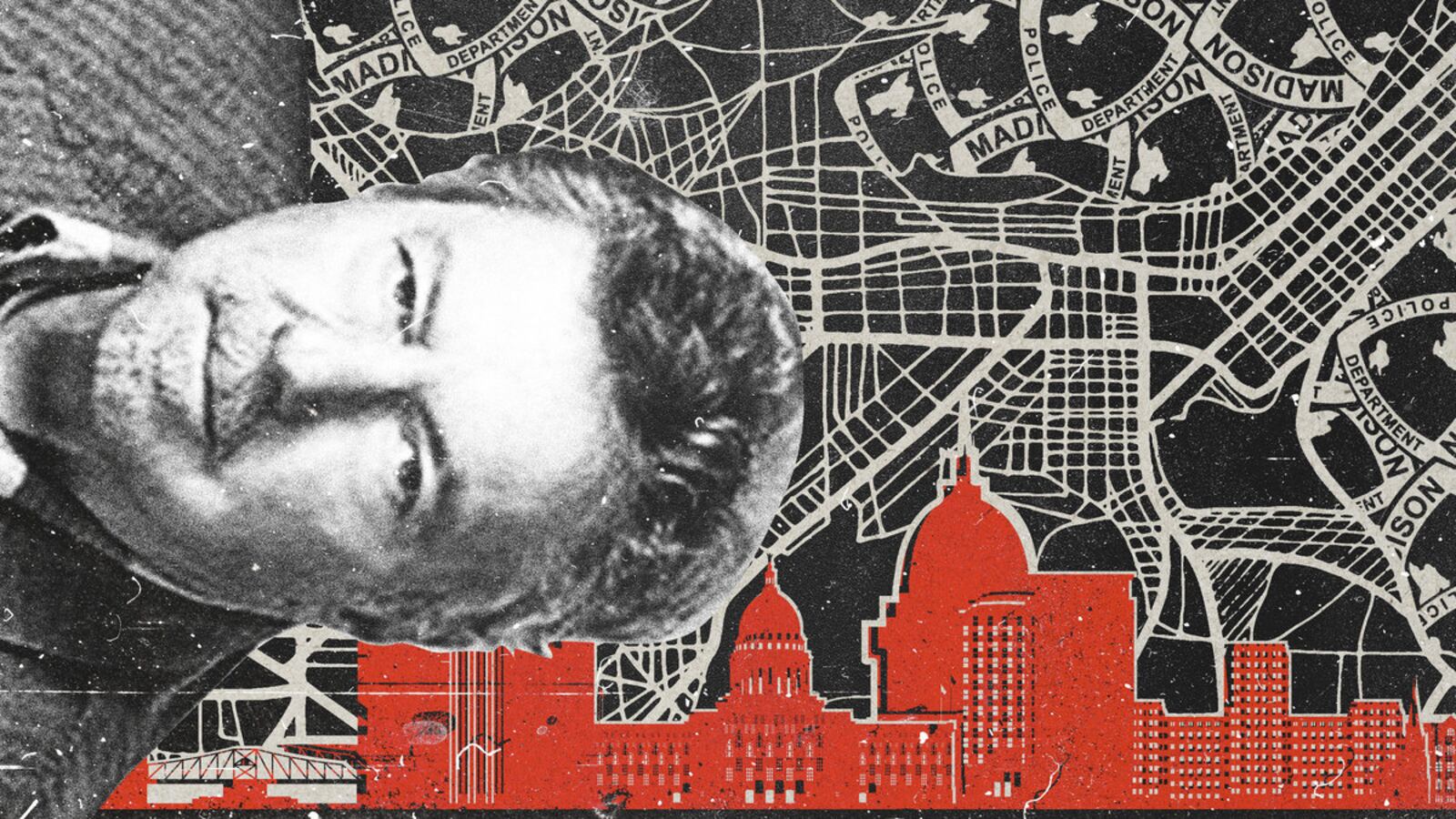

David Blaska is no stranger to political controversy. But the 71-year-old provocateur’s latest campaign might be his most bizarre yet.

The conservative blogger, who says he’s been “annoying liberals” in Madison, Wisconsin, since birth, took his game to another level this week when he filed a federal lawsuit against the city, claiming that he had been the victim of racial discrimination.

His beef? He says he was not chosen for a seat on the city’s new police oversight board because he’s white—and he’s pushing everyone from officials to police-reform activists in the progressive state capital and college town toward despair.

“I’m sort of like John the Baptist,” Blaska told The Daily Beast. “Eventually, I will get my head served to me on a platter.”

The oversight board was created in September, following a four-year study into the practices of the Madison Police Department. It turned up evidence of a frayed relationship between the department and communities of color, and as a result, the city’s common council spelled out in a resolution that 50 percent of the new 13-member board had to be Black, and that there would be at least one Asian, Latinx, and Native American member, as well.

That left four seats up for grabs for white people like Blaska. But he came up empty after applying last fall.

Blaska told The Daily Beast he doesn’t particularly care about not being on the board. In fact, he admitted, he doesn’t think the board is necessary. (“Police are not the problem in Madison,” he said, arguing that “crime” is.) His real issue, he said, is the resolution spelling out which races or ethnicities can and can’t be on the board, which he says is unconstitutional. “It’s illegal to discriminate by race,” he continued.

David Oppenheimer, a law professor and director of the Berkeley Center on Comparative Equality and Anti-Discrimination Law, reviewed Blaska’s complaint and called Madison’s resolution “unusual.” He said Blaska has an argument for discrimination given federal case law that has “made it pretty clear that in most circumstances, government cannot use race to exclude people from participation.”

But, he said, the city could prevail if it came up with a “compelling” reason for why the diversity quotas are needed.

Many residents of the Wisconsin capital believe that reason is crystal clear after a year of police protest rage: Cops treat communities of color differently than other populations, and therefore the express input of those community members is needed to change the situation. That’s part of how the city plans to beat the lawsuit, citing a dynamic experts and many insiders say is obvious to virtually everyone except Blaska.

Keith Findley is a law professor at the University of Madison-Wisconsin—the institution that powers life in town—and one of at least two white members of the oversight board. He said in an interview that the purpose of the race designations for seats was to take a “very specific, targeted approach” to address “a history of racial disparity and breakdown in trust between minority communities and the police department.”

“That can only happen if the board reflects heavy representation of the very communities where trust is lacking,” he told The Daily Beast. Filling the board with people like Blaska, who he noted is not one to criticize law enforcement, would defeat the purpose. “It was a bridge-building enterprise,” he said of the board, “and there is simply no need to build a bridge between David Blaska and the police department.”

For his part, Blaska claimed he applied because he thought the board needed “at least one person who is generally supportive of police,” suggesting its current makeup is anti-cop.

A spokesman for the Madison Police Department did not respond to questions about their policing of Black residents versus white ones, but did say the department was not opposed to the oversight board.

Blaska is not exactly a hapless gadfly. A former Dane County supervisor who held his role in public office from the late 1990s to the early 2000s, he also spent a stint as a deputy press secretary to former Wisconsin Republican Gov. Tommy Thompson in 1998.

Before that, he was a reporter for The Capital Times. But since 2017, he said, his writing has mostly appeared on his blog, where he frequently sounds off on right-wing boogeymen like critical race theory and calls to defund the police. He also sensationally blames progressive policies for the rise in violent crime in cities like New York. “Progressivism is a leading cause of death—especially fatal to minorities,” he wrote recently.

Blaska told The Daily Beast that he doesn’t believe Madison has a problem with over-policing minority communities, and that the city should spend its energy and resources focusing on crime instead of racism. “It’s looking at the wrong problem,” he said.

In fact, he said, echoing decades of conservative fantasy about race-blindness, he’d like to do away with racial categories altogether.

“What is Tiger Woods?” he asked in an interview, apparently not joking. “He’s a great golfer and a fast driver, right? That’s what he is. Otherwise, I’m hard pressed to say what he is, racially.”

Blaska has long been a conservative, albeit not necessarily an easy one to pin down. He said he didn’t vote for Donald Trump in 2016, but did in 2020 because he believes the Democratic Party has been “taken over by extremists.” Although he parrots right-wing talking points, he’s quick to claim he’s not that extreme. “I’m not an Oathkeeper,” he said, adding that he thought the Capitol riot on Jan. 6 was “an abomination.”

Though Madison has always been a liberal town, lately, he said, it has “gone off the deep end” with “woke, progressive ideas,” adding that the “racial quotas” of the police oversight board are a prime example. He said he hoped to steer the city away from a fixation on identity politics and, in fact, sees it as his calling, given that there are so few conservative voices in the city.

Brian Benford, a Black alderman on the city’s common council, sees things rather differently.

According to Benford, Blaska is the “token conservative” in the city. He said he didn’t mind Blaska questioning the resolution passed in September. But he said filing a lawsuit against it and simply rejecting the core reasons why the board was created, such as the over-policing of minority communities, displays a certain level of dismissiveness he can only chalk up to racism.

“This is a social justice issue and he’s clearly a racist,” Benford said.

Blaska denied that, but said the label is something often flung his way by his opponents. “If you disagree, they call you racist. This is how they stifle dissent,” he told The Daily Beast.

Benford said Blaska’s comments about policing are typical for people outside of communities of color in Madison who don’t understand what it is like to live in them. “I despise when white people try to illustrate the lives of BIPOC people like they would know,” he said. “Like they would have any clue.”

The alderman said the Madison Police Department is overall an “exemplary” one compared to others in the country. But he also said that in his experience, certain neighborhoods are over-policed, and Black residents in particular have a disproportionate number of interactions with the police department considering their small share of the population.

“Mr. Blaska would have to be totally delusional if he can’t read the racial disparities,” he continued. “They’re really clear.”

The numbers back the alderman up.

Use-of-force reports from the Madison Police Department between 2016 and 2020 first published by Blaska’s old haunt The Capital Times showed that Madison police used force in less than 1 percent of their interactions with citizens.

But the reports also showed that in a city where about 80 percent of residents are white and fewer than 10 percent are Black, more than 40 percent of the total use-of-force instances between 2016 and 2018 were inflicted upon Black residents. In 2019, the data showed, Black residents were involved in nearly 57 percent of use-of-force incidents versus 32 percent for white residents.

In 2015, the police department also came under scrutiny for the shooting death of Tony Robinson. The 19-year-old, unarmed Black man was killed after reports that he was acting erratically in his neighborhood, and an encounter in his apartment with a white police officer. The cop was not charged, and the shooting was cleared by the department, but Findley recalled that it caused long-held tensions about the treatment of minority communities in the city to erupt into protest.

In response to calls for reform, the city formed a committee to review the department’s culture, training, policies, and procedures, and in particular the relationship between police and communities of color. Findley, who was a chair of a committee for its last two years before it issued 177 recommendations to the police department in 2019, said the independent civilian oversight board was the “capstone” recommendation.

Critics of the board, like Blaska, say it is unnecessary because the city already has an independent Police and Fire Commission charged with personnel matters within the police department, as well as handling citizen complaints.

But Findley said the board is expressly different from the commission, which he previously served on, and called a “reactive” body rather than a proactive one. The commission takes recommendations from the police department and can only weigh in on individual complaints about officers, rather than more systemic issues like use-of-force policies, how the department deals with mental health crises, or stop-and-frisk tactics, he said.

The Police and Fire Commission did not respond to a request for comment.

Findley said the new oversight board does not have the power to compel the police department to take any action like the commission. But it can access department data and make recommendations about policies and practices with the direct input of members of the community that might be most affected by them. One of the more important things the board can do, he added, is provide legal counsel to civilians making complaints against the police. In the past, they may have had to navigate the process alone while officers were represented by union counsel.

“It was an unbalanced playing field,” the law professor said.

Findley was nominated to his position on the board by the Mayor of Madison, Satya Rhodes-Conway, who declined an interview request for this story.

According to Michael Haas, Madison’s city attorney, the mayor and common council nominated four positions on the board. The other nine positions were filled after nine social-justice oriented organizations representing communities of color, formerly incarcerated residents, and LGBTQ residents, among others, nominated three people each. One person from each group’s list was chosen by the city.

Haas said residents can also “self-nominate,” which is the route Blaska went.

Although Blaska paints the board members as high-powered public officials, Findley said, they are essentially volunteers. (They are paid a $100 monthly stipend, which he said is intended to help lower-income members cover any transportation costs or child-care needs in order to attend meetings.) The real power of the board, he said, rests in a still-unfilled independent monitor position, which will be a full-time and paid role that he said will drive the board and use their suggestions to make recommendations.

The position, he noted, does not have any specific race or ethnicity requirements.

Haas argued the “unique process” of filling the board was designed to “give all communities in the city an opportunity to be consulted and have input” in the process of improving relationships between the police and the community.

Blaska argued that while that all sounds well and good, it doesn’t change the fact that the specific demands for the race of board members is not legal. And he’s got some muscle behind him.

His lawsuit is represented by lawyers from the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty, a conservative non-profit firm described by its president, Rick Esenberg, as “the ACLU with a somewhat different mission statement.” Recently, they’ve brought other cases in the state pushing back against COVID-19 restrictions, absentee ballot boxes, and provisions in President Biden’s American Rescue Plan Act that offer loan forgiveness to farmers based on race.

When it comes to Blaska’s case, Esenberg said that although he was not opposed to a police oversight board, it is clear Madison crossed a line when it spelled out how many seats in the public body must be reserved for members of a specific racial group. “I’m hard pressed, aside from some place like South Africa or the Jim Crow South, to find an example of this happening in the modern era,” he said.

The lawsuit calls for the resolution establishing the board’s makeup be declared unconstitutional and that the city disband the board and start a new one without any regard to race.

Esenberg acknowledged that the court could side in the city’s favor if they prove there’s an important reason for the racial designations and that they’re “narrowly” tailored.“I just don’t think they can show that,” he said.

Haas, the city attorney, said outside counsel will be representing the city in the case and hasn’t been named yet. But he believes the city will make a compelling argument that the board’s composition was in direct response to the fact that “communities of color have had more police contacts and higher rates of incarceration than others in our society for decades.”

Benford, who was elected to the common council—making him an alderman—after the resolution was passed, said he applauded the diversity requirements and felt proud that the city and mayor seemed to be making a concerted effort to address systemic policing issues and give impacted communities a voice in the majority-white city.

The lawsuit and Blaska’s arguments about constitutionality, he argued, were little more than bad-faith attempts to reverse progress.

“It just feels like I’ve seen this play out so many times, especially during Trump’s presidency,” he said. “Some white men are emboldened to do everything without the smoke screens anymore. It’s right there in your face. They stripped away the veneer.”