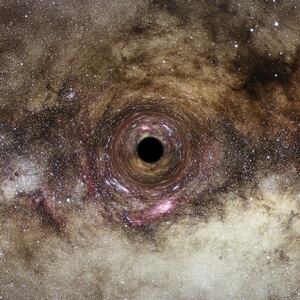

Somewhere right now in the infinite span of our universe, a star is approaching the gaping maw of a black hole. Once it gets close enough, it’ll start to get pulled apart, in a process delightfully dubbed “spaghettification”—resulting in a massive jet of energy that can potentially be detected from Earth.

This phenomenon is known as a tidal disruption event (TDE). It’s rare. But if astronomers spot one, it gives them the chance to observe a black hole eating celestial objects in action.

That’s exactly what happened when an international team of astronomers witnessed the most distant TDE in recorded history. In a paper published Nov. 30 in the journals Nature and Nature Astronomy, the researchers reported detecting a supermassive black hole swallowing a star roughly 12.4 billion light years away in an event dubbed AT2022cmc. The TDE unleashed a jet of energy that was so bright and massive that it was observable using optical telescopes.

The study’s authors now say that the event gave them insights into how supermassive black holes form—and also into what our universe looked like when it was young.

“The luminous jet of material was launched almost at the speed of light and the jet was pointing in our direction,” Igon Andreoni, an astronomer at the University of Maryland and co-leader of the Nature paper, said to The Daily Beast. “This is an extremely rare phenomenon and it is even rarer that it can be observed at all because the jet is collimated, which means that we can observe it only if we are very close to the direction in which it is pointing.”

Andreoni adds that the light from the event traveled through the cosmos for roughly 8.5 billion years before it reached us. That means it occurred when the universe was just a third of its current age.

This just highlights how bright AT2022cmc was when it occurred. While researchers aren’t completely certain, the study’s authors surmise that this was due to how the black hole was moving at the time it swallowed the star.

“[We] argue that the black hole was likely spinning fast, which might have an important role for these powerful jets to be launched,” Anderoni said. “We also concluded that the black hole, despite being ‘supermassive,’ is not more massive than most black holes at the center of galaxies—‘only’ a few hundreds of millions of times the mass of our Sun.”

The researchers now plan to build off of the research using newer telescopes including the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory being built in Chile. Once completed, it’ll be able to view the entire observable sky every few nights.

Anderoni hopes the new observatory will be able to “unveil a whole population of jetted TDEs” using optical telescopes.

“Unveiling a population of such rare transients means that we can greatly improve our understanding of the violent universe,” he said.