It’s been rough for Earth. The only known planet to support life has gotten climatologically volatile as population grows in marginal land and climate change boosts the intensity of storms, floods, fires, and droughts. Understanding how the world is changing is the task of a fleet of tiny satellites constantly monitoring our lonely outpost in space.

But Planet Labs, Inc., a startup based in San Francisco, thinks there’s hope. Its satellites—“shoebox satellites” that carry compact cameras tracking every passing cloud—orbit just above the Earth’s atmosphere, snapping shots of the land below and goings ons, whether they be environmental or human caused.

Mike Safyan should know. He’s the launch director at Planet Labs, an urban microsatellite company nestled between social media companies and artisan coffee shops in San Francisco. On Halloween, the company launched several “shoebox satellites.”

Safyan doubles as one of the company's founding team, insisting the company headquarter in the heart of San Francisco. The company started in a garage in 2010, using off-the-shelf commercial hardware to build small satellites called Doves that could be cheaply deployed in large numbers. “We named them Dove satellites because we wanted the message to be just as important as the product,” Safyan explained. “These are assets to use space to help life on Earth.”

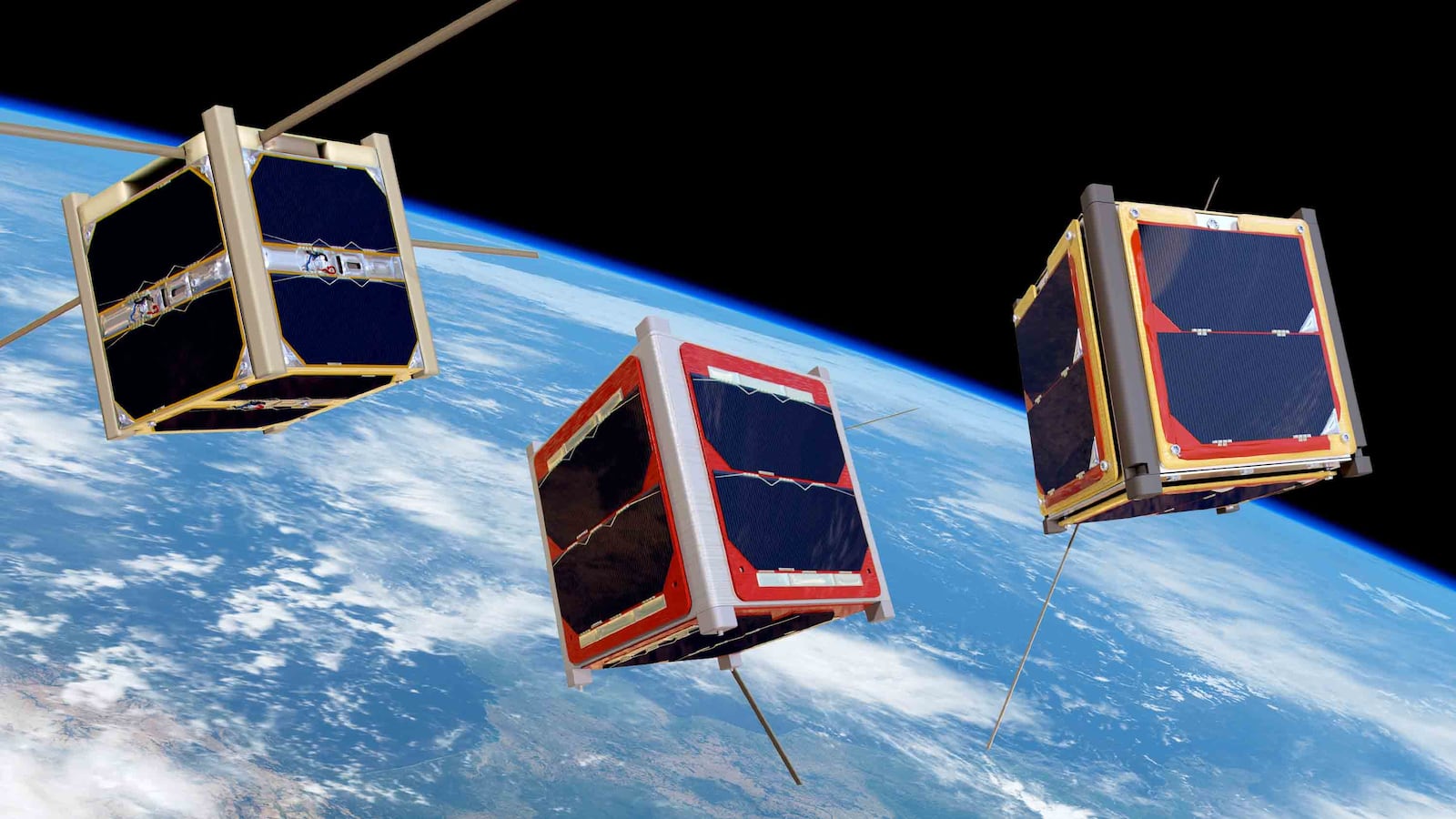

Doves carry only a camera and telescope, all packed into a standardized small satellite form called a cubesat. Without a propellent system, their orbits decay quickly, burning up as artificial shooting stars. To compensate, new Doves are launched a few times a year, hitchhiking on rockets dedicated to larger payloads of fancier satellites. Eighty-eight Doves were deployed in February; another 48 launched in July. On Halloween, the company launched another 10 satellites out of southern California. The expanded coverage will enhance everything from disaster response to industrial strategy.

The Doves orbital path sends them over the poles multiple times a day, which in turn allows Planet Labs to take even more images than it does at other locations. “We just hit record on the world's most unique and vulnerable places,” Alex Bakir, vice president of product and marketing, said.

Researchers are using that data to see how glacial flow is speeding up over time, glaciers are receding faster, and spotting cracks growing in ice sheets. Opening their data to researchers is good for the planet, but it’s also good for Planet Labs. “It turns out that big shipping companies also care about what’s happening at the poles because of shipping channels through the region,” he pointed out. This sort of unexpected crossover between research and commercial application is common, Bakir pointed out.

Planet’s first dedicated launch on Halloween was entirely dedicated to just Planet Labs satellites, instead of the usual mix of satellites from several companies. The rocket—nicknamed “Planet Express” for the launch—carried six SkySat satellites and four Dove cubesats. The larger SkySats carry higher-resolution cameras than the Doves, allowing Planet Labs to capture more detailed images over a smaller area. The Doves were manufactured in San Francisco and the SkySats were built 30 miles south in Palo Alto; they’re all launching out of Vandenberg in southern California. “It’s a cool confluence of California actors,” Safyan grinned.

Planet Labs took tradition on the road with this latest launch. “The first launch we ever had was in the morning,” Safyan recalled, explaining their launch-day tradition of eating pancakes. “Pancakes are always an important part of launch readiness.” Safyan scouted out a diner full of aerospace memorabilia to take the team for pancakes while awaiting the countdown to blastoff. “It’s a perfect spot!”

That mix of seriousness and fun permeates the building. The sign-in lobby has a collection of stickers highlighting notable women in computer science history. The lunchroom is decorated with graphic paintings by the artist-in-residence, and a collection of musical instruments leans against the wall waiting to be played. In the center of one table is what I first mistake for a real-size model of a Dove, only be be corrected and told it’s the singed, sandy survivor of a rocket explosion a few years previous.

I was led upstairs to a glass-enclosed conference room on the side of an open-plan loft full of desks. Although our path was direct, I spotted a few fictional starships as desk decor. A pulley system links the kitchen to mission control, delivering freshly-baked cookies to the huddle of desks below a large screen tracking the hundreds of tiny satellites.

“Translation from remote sensing to useful information is what it's all about for us right now,” Bakir said. The company is using machine learning to make it easier for their clients to find interesting things within the extensive and growing image archive.

Measuring fields to estimate crop yield and mapping are classic uses for remote sensing. “Roads are not as stable as you think,” Bakir laughed. In everything from disaster zones to developing economies, a rapidly changing situation on the ground can quickly render maps outdated. So Planet is partnering with CrowdAI to map roads from their satellite images in rapidly-developing regions, or identifying roads in Houston flooded by Hurricane Harvey.

The insurance industry is catching on to how useful rapid satellite imagery can be, with one unnamed firm requesting additional coastal images before hurricane season in order to speed up processing damage claims. “We've had a lot of these quite upsetting and difficult weather events happening,” Bakir said. “We are able to go back and take another look, which allows insurance claims to be processed a lot quicker.”

While agriculture and governments frequently use remote sensing, Planet Labs is reaching a new industry by drawing the insurance industry into realizing how useful it could be. The trick, explains Bakir, is by providing context and analysis tools instead of just raw images. “That industry would never have used imagery from space without some of these information translation tools,” Bakir said.

But Planet Labs’ biggest asset is that it is recording images everywhere all the time instead of waiting for a client to request images of a particular area. “A lot of times places don't become newsworthy or image worthy until there has been a disaster,” Safyan explained. “Not only do we have imagery of the disaster sometimes day-of or post-imagery, but we also have pre-imagery so you can actually see what the changes were.”

Planet Labs responds to the International Space Charter, whose charter has been activated for 30 disasters thus far in 2017, triggering Planet Labs to release rapid satellite imagery to first responders and aid organizations. Planet Labs helped identify damage, flooded areas, and coastal erosion after each hurricane this season. Although the charter wasn’t officially activated, they also assisted with the North Bay fires in California. In the future, they hope their images can be used in conjunction with NASA’s fire-spotting MODIS satellite to help pinpoint the exact location of new fires more quickly.

Doves are medium-resolution cameras at 3 meters per pixel. That’s good enough to identify a vehicle as a pixel, but not with enough detail to differentiate between them. Their slightly-larger SkySats have better resolution at 80 centimeters per pixel, enough to distinguish between cars or trucks and identify colours, but not enough to track a particular individual day after day. “You can see economic activity in a port but you couldn't say this license plate car was here at this time,” Sayfn said. This means despite constantly recording changes on Earth, Planet Labs's imagery isn’t a significant privacy concern.

Planet Labs opens their datasets to researchers, helping teams develop new methods to find ships that turn off their beacons to engage in illegal fishing, trigger deforestation alerts, or even track penguin colonies from space. That data is in turn shared.

Opening their data to researchers is good for the planet, but it’s also good for Planet Labs. “It turns out that big shipping companies also care about what’s happening at the poles because of shipping channels through the region,” he pointed out. This sort of unexpected crossover between research and commercial application is common, Bakir explained.

“Space doesn't have to be so serious,” Safyan told me about what makes the mix of culture, technology, and applications at Planet Labs so special. “It can be fun, it can be creative, but it can also be really useful.”