Yoni Netanyahu was my hero.

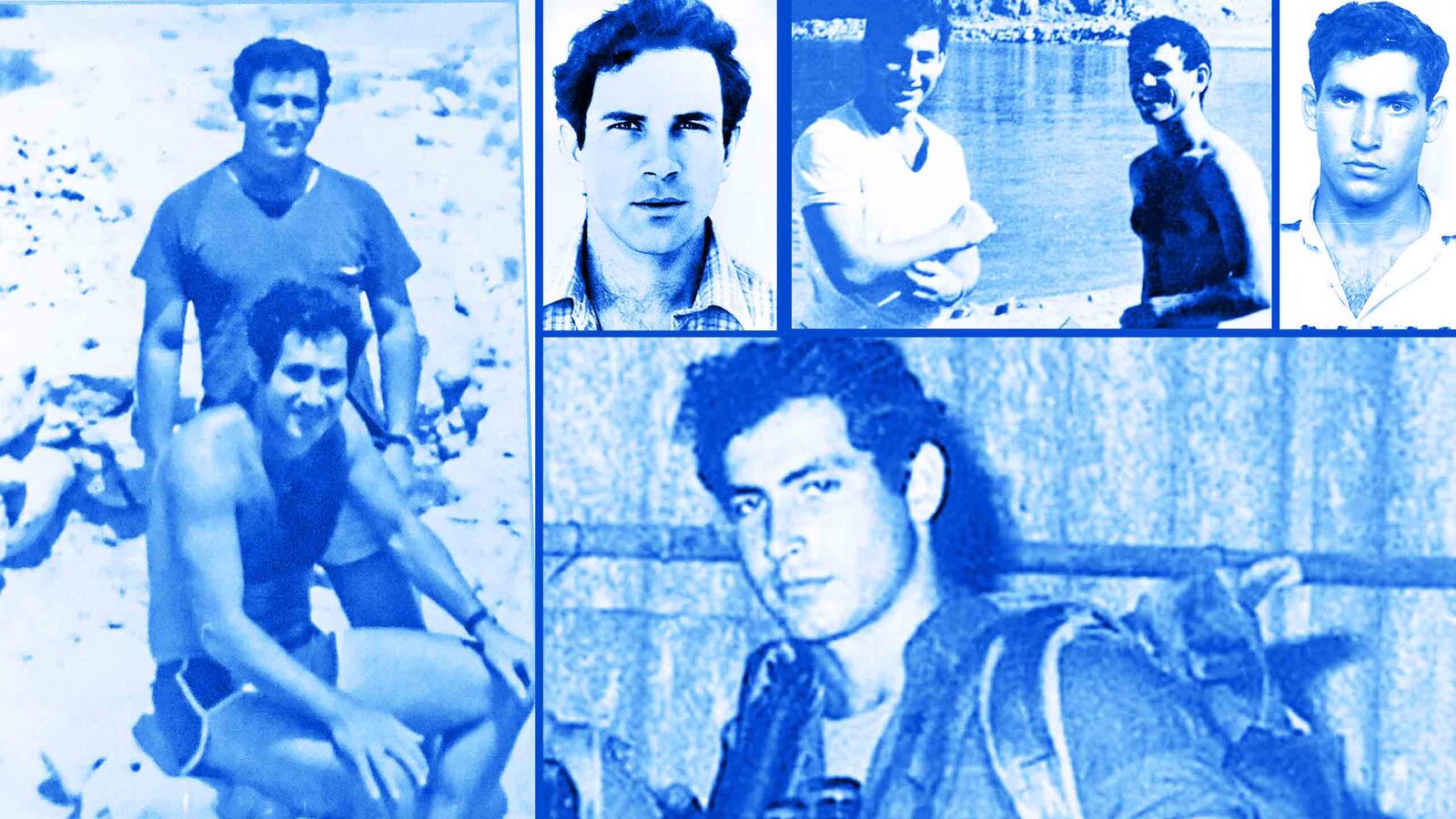

I was 12 or 13 years old, watching “Raid on Entebbe” at my Jewish summer camp. It was one of three movies about the daring Israeli mission to rescue 248 hostages being held at the Uganda airport by German and Palestinian hijackers. There was Netanyahu: young, handsome, heroic. And, tragically, the only Israeli soldier to die in the operation.

What 12-year-old boy wouldn’t idolize him?

Like James Dean, Yonatan Netanyahu died young, and is thus young forever. Even more handsome in person than in the movie, Netanyahu was already a war hero before Entebbe, having served in both the Six Day War and the Yom Kippur War. He might be prime minister one day, people said.

And then there was his brother Benjamin.

Although the brothers both served in the elite Sayeret Matkal unit, Bibi was more businessman than statesman. When the Entebbe operation took place, he was living in the United States under the name “Ben Nitay,” studying business at MIT. He worked at Boston Consulting for a few years—with Mitt Romney, as a matter of fact.

Yoni was the one destined to lead—until fate intervened and Bibi was thrust into his brother’s presumed role, becoming Israeli ambassador to the United States, then deputy prime minister, then the longest-serving prime minister in Israeli history.

Yoni was Joe Kennedy Jr.; Bibi was Jack. Yoni was Sonny Corleone; Bibi was Michael.

And now, 42 years after the Entebbe operation comes yet another film, 7 Days in Entebbe, retelling a story familiar to kids of my generation but probably unknown to millennials. On the surface, it’s a throwback to a time when Israelis were the good guys and Palestinians were terrorists; when the Israeli military rescued innocent civilians instead of interrogated, detained, and occupied them.

The film might also seem to come at an inconvenient time for Prime Minister Netanyahu. In contrast to his larger-than-life brother, Netanyahu has seemed all too human lately, as he is ensnared in yet another corruption inquiry, that, like the series of scandals in 1997-99, could well end his premiership. In a sense, 7 Days in Entebbe is like the tale of two Netanyahus: one heroic, one facing the possibility of ignominy.

Actually, things are a little more complicated.

7 Days is the first Entebbe film to depict what actually happened to Yoni Netanyahu: that he was killed at the beginning of the firefight in Entebbe, not the end, as the previous films depicted. This doesn’t mean he wasn’t a hero—he helped plan the raid, and led the commando force until he was shot. But it isn’t the story I remember.

7 Days also, controversially, centers on the experiences of the two German kidnappers, played by Daniel Bruhl and Rosamund Pike, who, while not entirely sympathetic, are still the most fully realized characters in the film. Neither their Palestinian cohorts nor their Israeli victims get the same level of attention.

And on the Israeli side, the film is more interested in the agonized decision-making of Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres than in the heroics of Yoni Netanyahu. Indeed, several studies undertaken in the years since the operation have suggested that Netanyahu made crucial mistakes in the execution of the raid that almost led to catastrophe. The film follows suit.

Just as 7 Days isn’t another tribute to Yoni Netanyahu, so it would be foolish to write a eulogy for Bibi. In fact, it now looks like he will survive his current scandal unless the Israeli attorney general—a one-time Netanyahu aide—issues a formal indictment. At the very least, that could take months.

In the meantime, Bibi is being Bibi: vociferously denying any corruption, clinging to office, rallying the base. Even in 1999, Bibi never resigned; Ehud Barak (incidentally, another planner of the Entebbe raid) defeated him. The guy does not quit.

Indeed, if Yoni Netanyahu died too young, Bibi Netanyahu seems never to die at all. So many political obituaries have been written by left-leaning pundits like me, so many “fatal blows” to his leadership, yet Bibi has outlasted them all.

Will the current scandal really be any different? Personally, I doubt it.

Yes, on Feb. 13, the Israeli police recommended an indictment on charges of bribery, fraud, and breach of trust. Yes, the charges are tawdry: $300,000 in gifts, allegations of back-room dealings for better press coverage, and plenty of side-plots involving abuse of state funds by Netanyahu’s much-despised wife, Sara; double-crosses and turncoat aides; the usual.

But Israelis have seen this all before—20 years ago, in fact, when the police recommended similar charges, when the details were just as tawdry, when Sara Netanyahu was also implicated… and nothing happened.

Really, the only thing that’s different between now and then are the names of Bibi’s opponents. All the ones from 1999 are history. Bibi is still here.

Not only here, but triumphant. Netanyahu’s once-outlandishly-conservative policies, and the ideology of his even more conservative father, Benzion Netanyahu, have prevailed in both Israel and the United States. Progressives like me think this is a calamity for both Israel and Palestine, but even we have to admit that Bibi has won, decisively.

Not just his ideas, but Bibi’s attitude—gruff, nationalistic, borderline-racist—has won as well. Israel is less democratic and more mean-spirited than ever before. And as far as America, Bibi was Trump before Trump was Trump.

In fact, maybe 7 Days in Entebbe could be seen as telling a different kind of story: a tale of two Netanyahus, and two different models of heroism.

Yoni’s is familiar: brave young soldier dies in the line of duty, rescuing innocent people from evildoers. But as the scholar Daniel Boyarin has argued in a series of books contrasting Jewish and Christian hero stories, that martyr narrative is more a Christian one than a Jewish one.

Early Christian martyrs died for God, like the savior himself. But contemporaneous Jewish leaders found ways to survive: making deals with Roman occupiers, sneaking around to evade capture, modifying their own religious traditions to favor accommodation over rebellion.

There aren’t many movies made about people like that, just as there aren’t many movies about people like Benjamin Netanyahu. But arguably, Jewish heroism is more about doing whatever it takes to survive than about nobly dying for a cause. And if that’s heroism, then, I hate to say it, but it’s Bibi who has been the hero.