To understand how a cult operates, one need look no further than the nightly news, where a charismatic strongman messiah preaches to his acolytes that he’s the only bulwark against a conspiratorial evil enemy, and then convinces them to behave in ways that are antithetical to their best interests. Still, for a more in-depth (and less politicized) view of such charlatans and the mesmerizing grip they hold over their flock, Oxygen’s Deadly Cults returns this Sunday, April 26, with eight new tales of sinister saviors and easily duped disciples. Insightful and sensationalistic in equal measure, the series’ second season illustrates that, whether in traditional or modern forms, these groups continue to flourish thanks to the megalomaniacal egos and greed of certain men, and the catastrophic gullibility and need of so many everyday individuals.

It’s a contemporary cult that gets initial attention from Deadly Cults, as its premiere episode trains its critical gaze on James Arthur Ray, a self-help huckster who rose to prominence in the 2006 film The Secret, which promoted the notion that one could achieve anything one wanted by simply believing in it. His participation in that film, as well as subsequent appearances on Oprah and Larry King’s talk shows, helped propel his seminar business, and as former followers such as Connie Joy and Melissa Phillips confess, they quickly found themselves hooked on his teachings. For them, Ray’s lessons were a gateway to personal growth, and thus worth the exorbitant costs required to move up his pyramid-structured “Journey of Power” curriculum—including the $10,000 demanded of participants who wanted to experience the apex of the course, “Spiritual Warriors.”

As depicted by Deadly Cults, Ray is a New Age version of an old-school televangelist crook, enticing clients with promises of enlightenment and satisfaction while not-so-subtly milking them dry. Unfortunately for him, though, his operation fell apart on Oct. 8, 2009, when, during an insanely intense sweat-lodge challenge at a “Spiritual Warriors” retreat, Ray wouldn’t allow followers to physically escape to fresh air, causing three attendees to die. The tragedy netted Ray two years behind bars for negligent homicide—and the loss of many devotees. And yet as the series indicates, he now continues to hawk his counterfeit wares, replete with new claims that his own misfortune is an example of the type of obstacle one can learn to overcome with his coaching.

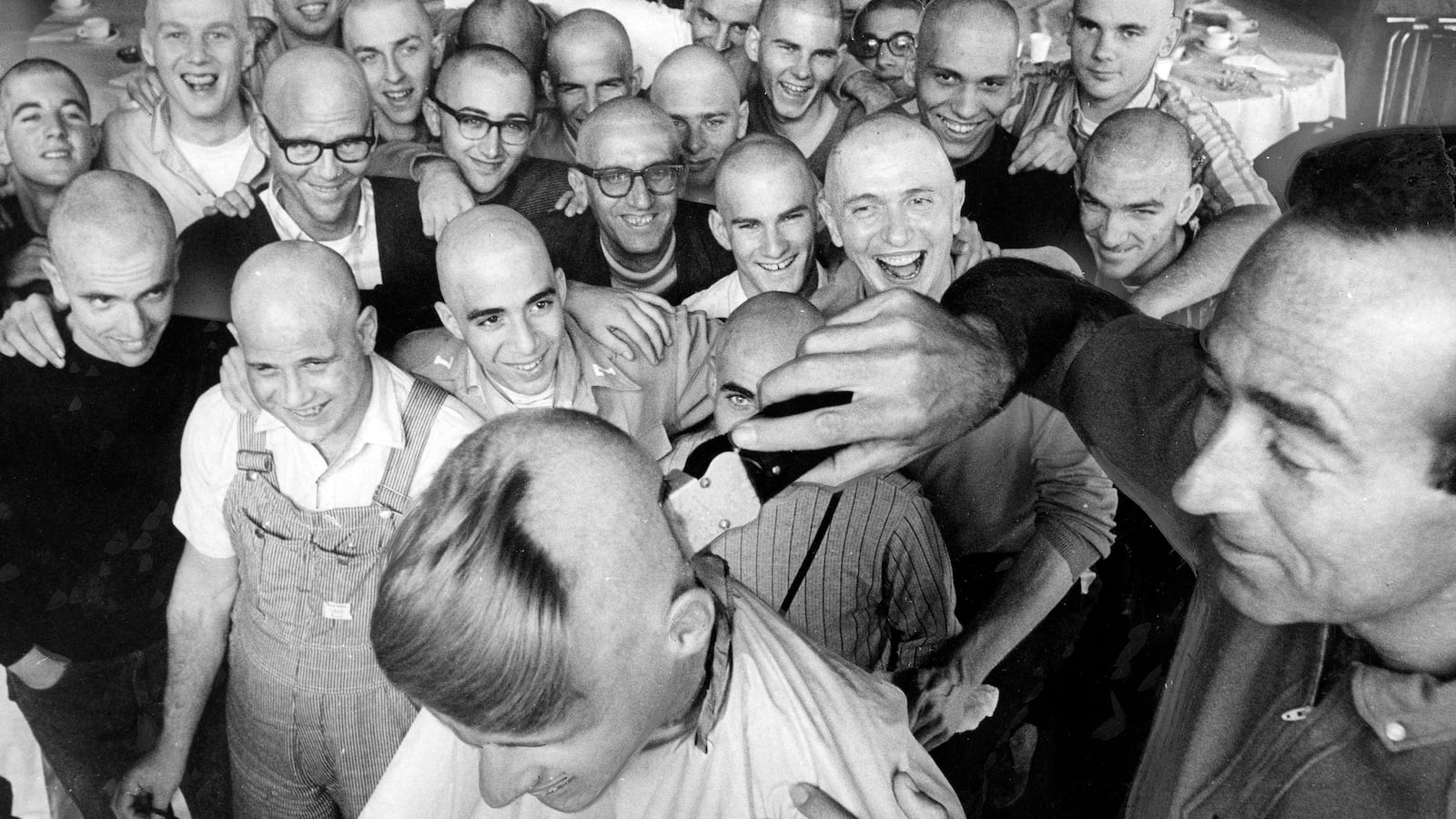

In virtually every episode of Deadly Cults, the basic story remains the same: men and women, susceptible to suggestion because of some misery or discontent, turn to exploitative self-anointed “Great Men” to fill a hole in themselves. Never is that more true than in the show’s eighth installment about Synanon, a Santa Monica, California, organization founded by Charles Dederich in 1958 as a drug and alcohol rehabilitation center. Convinced that traditional substance-abuse treatments weren’t getting the job done, Dederich—embracing the West Coast’s 1970s cultural trend toward alternative religions and communities—soon transformed Synanon into a veritable cult where angry, screaming therapy sessions were the norm; forced vasectomies and abortions were rampant; and where everyone at Synanon’s multiple locations received orders from their unimpeachable master via a wired PA system. Adherents shaved their heads, and an Imperial Marines squadron was formed to violently beat members, with “soldiers” even practicing a made-up form of martial arts known as “Syndo.”

Craziness only begat more craziness, and Dederich ran into serious trouble when he was successfully convicted by prosecutor Paul Morantz for abducting a woman off the beach and forcing her to join Synanon. In response, Dederich had two henchmen put a rattlesnake in Morantz’s mailbox—resulting in a near-fatal attack that left the lawyer in need of lifelong blood transfusions. The madman would eventually be pinned for that crime courtesy of transcriptions of his rantings, during which he articulated his hostile intentions toward the prosecutor, thus once again demonstrating how the hubris of cult leaders only leads to catastrophe, both for themselves and for their sheep.

That idea is incessantly reconfirmed by Deadly Cults. Take, for example, its portrait of Marshall Applewhite’s “Heaven’s Gate,” a gang of shaved-headed, castrated loonies who—believing they were aliens destined to reunite with their extraterrestrial brethren in a spacecraft hidden behind the Hale-Bopp comet—committed mass suicide in 1997. Just as bonkers is its snapshot of “Angel’s Landing,” a secluded Wichita, Kansas, outpost where Lou Castro fashioned himself a literal angel capable of bringing people back from the dead—a ruse that was so successful, he was able to both murder, and convince disciples to commit suicide, so he could receive their life insurance policies in order to keep his scam afloat. And for pure unbridled insanity, little tops the third episode about Steven Mineo, who compelled his girlfriend Barbara Rogers to shoot him dead, execution-style, because he was grief-stricken over his falling out with Sherry Shriner, an Internet-cult guru who—through social media posts, podcasts and YouTube videos—promoted the idea that the imminent apocalypse would be brought about by alien reptiles who lived among us and disguised themselves by wearing skin suits.

The fact that anyone could believe such a laughable story—which is taken straight from the 1980s TV series V—proves that there are many people so desperate for answers to their problems and failings that they’ll buy any fanciful fiction. Far from subtle, Deadly Cults delivers its material with melodramatic flair, full of shadowy dramatic recreations that can tip into cheesiness, wannabe-suspenseful scores full of mounting drumbeats, and whooshing transitional sound effects. Yet despite its exaggerated storytelling elements, it benefits from solid archival footage, especially in the case of “Heaven’s Gate,” whose members saw fit to record farewell videos in which they express excitement and joy over their forthcoming celestial ascension. And it’s bolstered by a raft of illuminating interviews with principal players, and survivors, who are candid even when their comments shine a less-than-flattering light on their own naivety.

In those first-person accounts, Deadly Cults transcends its formal shortcomings to provide insight into the skewed psychological reasons that cause many individuals to become seduced by brainwashing cults—and to follow them, wholeheartedly, to the grave.