In 1843 shortly after his return from the battlefields of the First Anglo-Afghan War, the army chaplain in Jalalabad, Rev. G.H. Gleig, wrote a memoir about the disastrous expedition of which he was one of the few survivors. It was, he wrote, “a war begun for no wise purpose, carried on with a strange mixture of rashness and timidity, brought to a close after suffering and disaster, without much glory attached either to the government which directed, or the great body of troops which waged it. Not one benefit, political or military, has been acquired with this war. Our eventual evacuation of the country resembled the retreat of an army defeated.”

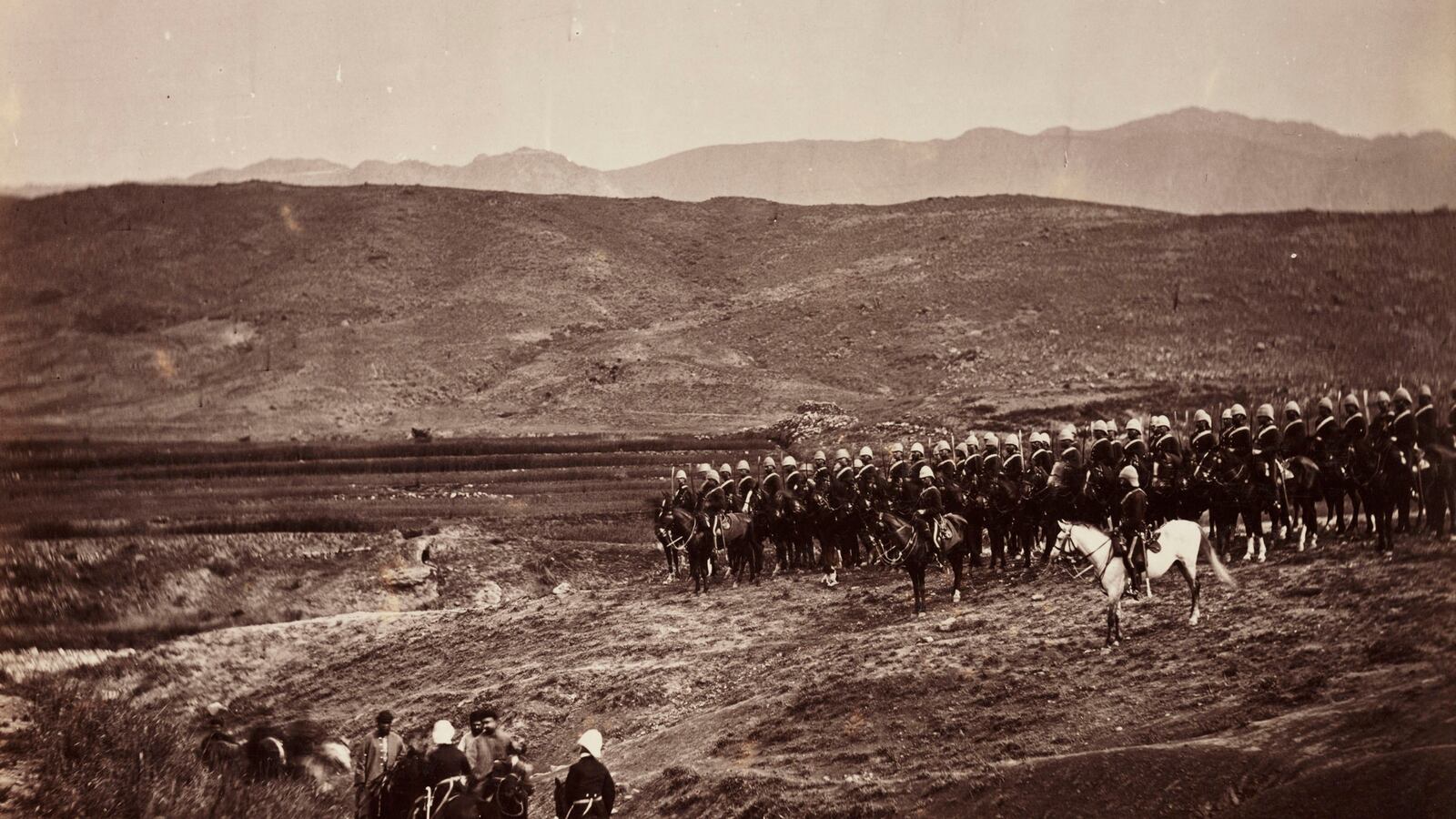

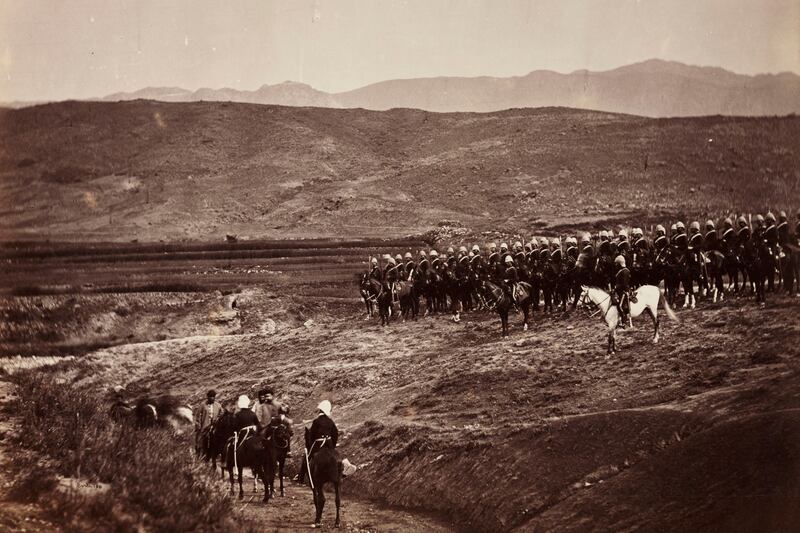

Gleig had a point. In the spring of 1839, the West invaded Afghanistan for the first time since Alexander the Great. Nearly 20,000 British and East India Company troops poured through the passes, ousted the popular ruler Dost Mohammad Khan, who the British believed to be pro-Russian, and reestablished on the throne Shah Shuja ul-Mulk, the exiled king who had spent the last 20 years as a British pensioner in India. On the way in, the British faced little resistance. But after little more than two years, the Afghans rose in answer to the call for jihad and Afghanistan exploded into rebellion.

In the winter of 1841–2, the two most-senior British envoys were assassinated in Kabul, followed, a few months later, by Shah Shuja himself. After a two-month siege, 18,500 cold, hungry, and leaderless East India Company troops and their followers retreated through the icy passes in the middle of winter. One by one, they were shot down by Afghan marksmen firing from behind boulders with their long-barreled jezails—the sniper rifles of the 19th century—as the troops trudged snow-blind and frostbitten through the icy mountain drifts.

After eight days on the death march, the last 50 survivors made their final stand at the village of Gandamak, near Jalalabad. As late as the 1970s, fragments of Victorian weaponry and military equipment could be found lying in the screes above the village. Even today, the hill is still covered with bleached British bones. Out of the 18,500-strong party that left Kabul, only one man, Dr. Brydon, made it back to the British garrison in Jalalabad. A handful of British officers and their wives were taken hostage; the rest were shot. Meanwhile, the Indian sepoys who made up the bulk of the army were either sold en masse into slavery in Central Asia, or disarmed, stripped naked, and left to perish in the snow.

The First Anglo-Afghan war was arguably the greatest military humiliation ever suffered by the West in the East: an entire army of what was then the most powerful military nation in the world utterly routed and destroyed by poorly equipped tribesmen. For Afghans, the British defeat of 1842 became a symbol of freedom from foreign invasion, and of the determination of Afghans to refuse to be ruled ever again by any foreign power. The diplomatic quarter of Kabul is still named after the Afghan leader who oversaw the rout of the British in 1842: Dost Mohammad’s son, Wazir Akbar Khan.

But 1842 wasn’t the last time the Afghans would see off their would-be invaders and occupiers. In the 1980s it was the Russians’ withdrawal from their failed occupation of Afghanistan that triggered the beginning of the end of the Soviet Union. Less than 20 years later, in 2001, British and American troops arrived in Afghanistan where they proceeded to begin losing what was, in Britain’s case, its fourth war in that country. As before, in the end, despite all the billions of dollars handed out, the training of an entire army of Afghan troops, and the infinitely superior weaponry of the occupiers, the Afghan resistance succeeded again in propelling the hated Kafirs out the exit.

It was as the latest neo-colonial adventure in Afghanistan was just beginning to turn sour in 2006, and the commentators were first beginning to predict new Gandamaks, that I began thinking of writing a new history of the West’s first failed attempt at controlling Afghanistan. After an easy conquest and the successful installation of a pro-Western puppet ruler, the regime was facing increasingly widespread resistance. History was clearly beginning to repeat itself.

In the course of the initial research, I visited many of the places associated with the war. In Herat I paid my respects to the grave of Dost Mohammad Khan at the Sufi shrine of Gaza Gagh. On arrival in Kandahar, the car sent to pick me up from the airport received a sniper shot through its back window as it neared the perimeter; later I stood at the shrine of Baba Wali on the edge of town and saw an IED blow up a U.S. patrol as it crossed the Arghandab River, then as now the frontier between the occupied zone and the area controlled by the Afghan resistance. In Kabul I managed to get permission to visit the Bala Hisar, once Shah Shuja’s citadel, now the headquarters of the Afghan Army’s intelligence corps, where reports about Taliban movements are evaluated amid a litter of spiked British cannon from 1842 and upturned Soviet T-72 tanks from the 1980s.

'The closer I looked, the more the West’s first disastrous entanglement in Afghanistan seemed to resemble the neo-colonial adventures of our own day. For the war of 1839 was waged on the basis of dubious and doctored intelligence about a virtually nonexistent threat: information about a single Russian envoy to Kabul was exaggerated and manipulated by a group of ambitious and ideologically driven hawks to create a scare—in this case, about a phantom Russian invasion. As John MacNeill, the Russophobe British ambassador wrote from Teheran: “We should declare that he who is not with us is against us ... We must secure Afghanistan.” Thus was brought about an unnecessary, expensive, and entirely avoidable war.

More astonishing still, Shah Shuja, so I learned, was a Popalzai, from the same subtribe as President Hamid Karzai, while his principal opponents were the Ghilzai tribe, who today make up the bulk of the Taliban’s foot soldiers: the Taliban leader, Mullah Omar, is from the Ghilzai’s Hotak ruling clan, as was the leading resistance fighter, Mohammad Shah Khan, who supervised the slaughter of the Kabul army in the Khord Kabul in 1841.

The problems that precede the humiliating withdrawal from Afghanistan are unchanged: with all resources poured into defense, then as now, the occupation brings few tangible signs of improvement or development; instead, the presence of large numbers of well-paid foreign troops causes the cost of food and provisions to rise, and living standards to fall; under Western occupation, the Afghans invariably feel they are getting poorer, not richer.

There are other uncanny similarities, too: in both cases the war effort was partially privatized: in 1839, alongside the British army proper came troops belonging to a corporation, the East India Company, just as today the U.S. has subcontracted much of the security in Afghanistan to companies like Blackstone. In both cases, the commercial imperatives of the corporations soon come to clash with the political agendas of the politicians.

In both cases, one of the biggest problems was that the ruler installed by the West resisted being used as a puppet and gradually turned on his backers. Recently, President Hamid Karzai has begun describing NATO forces as an army of occupation and threatened to join the Taliban if Washington kept putting pressure on him. Shah Shuja did much the same to the British toward the end of his rule.

When I published Return of a King in India in January, Karzai read my book within a fortnight of publication and invited me to Kabul to talk about Shuja. His view was that the U.S. was doing to him what the British had done to Shah Shuja 170 years ago: “The lies Lord Auckland told Dost Mohammad Khan, that we don’t want to interfere with your country, that’s exactly what they tell us today, the Americans and all the others,” he said. “Our so-called current allies behave to us just as the British did to my ancestor. They tried to do exactly as they did in the 19th century." Karzai made it clear that he thought Shah Shuja didn't stress his independence enough and Karzai, having learned the lessons of history, was never going to allow himself to be remembered as anyone’s puppet.

We in the West may have forgotten the details of this history that did so much to inform and mold the Afghans’ hatred of foreign rule; but the Afghans have not: in village after village I found that the names of all the participants in the drama were still alive as if the event had taken place two years ago, not two centuries. In particular, Shah Shuja remains a symbol of quisling treachery in Afghanistan: in 2001, the Taliban asked their young men, “Do you want to be remembered as a son of Shah Shuja or as a son of Dost Mohammad?”

The failures of 170 years ago do still hold important lessons and warnings for us today, and it is still not too late to learn some lessons from the mistakes of the 19th century. Otherwise, the West’s fourth war in the country looks likely to end with as few political gains as the first three, and like them to terminate in an embarrassing withdrawal after a humiliating defeat, with Afghanistan yet again left in tribal chaos and quite possibly ruled by the same government that the war was originally fought to overthrow.

As George Lawrence, a veteran of that first war, who was taken hostage during the retreat, wrote to the London Times just before Britain blundered in to the Second Anglo-Afghan War 30 years later, “a new generation has arisen which, instead of profiting from the solemn lessons of the past, is willing and eager to embroil us in the affairs of that turbulent and unhappy country ... The disaster of Retreat from Kabul should stand forever a warning to the Statesmen of the future not to repeat the policies that bore such bitter fruit in 1839-42.”

William Dalrymple will be speaking about his new book, Return of the King: The Battle for Afghanistan 1839-42, at The Asia Society in New York City on April 22; Politics & Prose in Washington, D.C., on the 24th; Harvard University’s Mahindra Humanities Center on the 25th; Asia Pacific Museum in Pasadena, California, on the 28th; the Getty Museum in Los Angeles on the 30th; Mechanics Library Institute in San Francisco on May 1; Seattle Asian Art Museum on the 2nd; The Freer Sackler in Washington, D.C., on the 3rd; and the Metropolitan Museum of Art on the 5th. Full details at williamdalrymple.com.