On the morning of Tuesday, June 14, 1994, my husband, the father of our four children under the age of 5, kissed me goodbye. I sensed heightened anxiety as we stood at the top of the stairs in our Vermont home. He leaned toward me, our lips meeting one last time above the 2-month-old nestled in the folds of my white cotton nightgown, buttons between milky breasts left undone.

“I have an early morning meeting,” Peter said.

I watched from our picture window, swaying to calm both myself and the baby in my arms, as his black Subaru disappeared down the steep Bolton Valley Access Road.

It had been a rainy spring in our Green Mountains. Through June, the rivers still rushed madly with melt run-off. Peter knew this when he pulled alongside the guardrail of Richmond’s infamous Huntington Gorge.

Instead of driving to Burlington for that meeting, Peter met his death by suicide in the foaming, churning waters funneling through steep rock formations. The current so strong and water running so high, the search team of police investigators took three days to find his lifeless body resting in one of the lower potholes. That image and phrase in the Burlington Free Press of “grim-faced state police divers” standing waist-deep encircling my husband’s drowned body remains carved into memory.

On Sunday, June 19, 1994—Father’s Day—the Richmond Congregational Church filled beyond capacity for Peter’s funeral. Will was the only one of our four children old enough to attend. I can still feel the grip of that 4-year-old’s hand as we walked between packed pews, can still see him climbing on the pile of dirt next to the hole dug at Waitsfield’s Common Cemetery for Daddy’s grave.

Two policemen had shown up on my doorstep the day Peter had gone missing, holding a brown paper bag containing two pieces of paper found on the passenger seat of his car. Jenny, Will, Lillian, Sam + Charlie, he wrote at 7:15 a.m. on his Burlington Free Press notepaper, I really do love you. You will be O.K. without me. One line on the second page of his note confused me: This thing has been in me for years, it was time to come out.

Decades later, this message would become horrifyingly clear.

Grief has no expiration date.

Neither did my possessed and persistent quest to piece together evidence surrounding my husband’s sudden, tragic death. How could this young man with so much to live for—a solid advertising career, adoring wife, adorable children, adored among friends for his fun-loving spirit—depart like that? What had I missed? What did I do—or not do? Was it my fault?

Twenty-three years later, on the afternoon of Tuesday, Aug. 22, 2017, at 3:36 p.m., an email arrived from one Edward Mechmann with the heading, “Complaint against Fr. Malone.”

“I am the Safe Environment Coordinator for the Archdiocese of New York. As such, I oversee the child protection programs of the Archdiocese…

“First of all, on behalf of the Archdiocese, please permit me to express my deep regret and sorrow that your husband was abused by one of our priests.”

Your husband was abused by one of our priests. My well-practiced self-control—honed by years of survival and needing to care for our children following Peter’s suicide—dissipated on the spot. I’d suspected this, yes. I’d sought out this very truth. I’d been certain in my heart that this happened to my late husband. But, in that moment, I doubled over, my body crippled by uncontrollable crying. For Peter. For me. For our children. For help.

The letter went on: “The sexual abuse of children and the ways in which these crimes and sins were addressed in the past have caused enormous pain, anger, and confusion. It has also led to awful tragedies like the death of your husband. No mere apology can rectify the harm that was done, but I hope that you will accept it in the spirit of profound sorrow in which it is offered.”

I wanted in this second to go back in time to save Peter. I wanted to hold that little boy. I wanted to hold that man I married. The song played at Peter’s funeral, Garth Brooks’ “The Dance,” was wrong about leaving it all to chance. I stood before my computer screen, tightened fist held high. This conspiracy of pedophiles must end. I must do something, anything to find and help others suffering in silence, to somehow catalyze the telling of stories, to ease this debilitating shame brought upon countless victims of this diabolical, predatory abuse.

The Safe Environment Coordinator—was I reading that right? The word “Safe”?—continued: “Last year, in establishing the Independent Reconciliation and Compensation Program of the Archdiocese, Cardinal Dolan said, ‘The program we are establishing today will, please God, help bring a measure of peace and healing to those who have suffered abuse by a member of the clergy of this archdiocese…’”

The email stressed Dolan’s praise for Pope Francis before encouraging me to file a claim, offering me Catholic counseling services, concluding:

“Whatever you do, do all to the glory of God.” (1 Cor. 10:31)

This journey—from Peter’s suicide to the Church’s acknowledgment of its responsibility—was long and circuitous, marked by fits and starts.

My first hint of the shadow cast over Peter’s life by the Church came on April 20, 2002, eight years after Peter’s death and the same year the Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” team was uncovering the sexual abuse epidemic in the Boston Archdiocese.

Mary—one of the four sisters who grew up next door to Peter’s home in Yonkers, New York, and who were like family during his childhood and adolescent years—sent me two articles from Westchester County’s Journal News.

The first, dated Wednesday, April 3, 2002—Charlie’s 8th birthday—chronicled the story of Kevin Mahoney, a former student at Peter’s high-school alma mater, whose priest-abuse claim was settled in 1998. According to reporters Gary Stern and Noreen O’Donnell, Kevin “seemed to have a classic Catholic upbringing, right out of a Bing Crosby movie.” He was an altar boy who “set out to become a man at Archbishop Stepinac High School in White Plains.”

Beneath the headline, “Ex-Stepinac priest named in sex case,” Mary’s sister, Rita, had attached a sticky note, “This one about Stepinac hit a nerve. There are more around here every day.”

Journal News articles that tipped off the author to her late husband’s abuse by a priest.

Courtesy Jenny GrosvenorWhy, I should have asked then, were Mary and Rita sending this news—to me?

Because—the buried truth I’d yet to uncover—this was about Peter.

The photograph I’ve kept of a young Peter in altar boy garb with the arm of a priest wrapped tightly and hand squeezing his shoulders will become symbolic—but not until 15 years later.

The photo of Peter in his altar boy vestments pinned to the author’s research bulletin board.

Courtesy Jenny GrosvenorCurious yet appalled by the phrase, to become a man, I read on about this Mahoney, a Stepinac class of ’76 graduate, captain of the football team, an A student who even supported the arm of Mother Teresa when she visited the all-boys Catholic school. I couldn’t help but wonder how all this figured into Kevin’s being targeted.

Further along in the Journal News article, the parallels—damages—I would later draw to Peter were uncanny: how Mahoney at 43 said his life was nearly ruined by this predator priest who abused him sexually for three years; how he’d kept it a secret, fearing no one would believe him; how depression over what happened led to his inability to hold a job, caused him to develop a drinking problem, and interfered with his ability to be a good husband and father to his own two sons; how it nearly destroyed him.

This same repressed traumatic experience, I’ll discover, did destroy Peter. But why didn’t he just tell? Further along in the article, I find a plausible answer: “If it was a Cub Scout leader, a teacher, I might have decked him,” Mahoney said. “But it’s different with a priest. He infiltrated my family, coming to Sunday dinner, for holidays. I just couldn’t deal with it at all. I couldn’t tell anyone.”

In my search for answers, in conversation with a lawyer friend who was in Kevin’s graduating class—a senior at Stepinac when Peter was a freshman—I became further enlightened.

“Yeah, funny,” Bert said. “There was this Father Malone. It’s kinda creepy now that I think about it, how he’d wear a cape and carry a crop around. Pretty masochistic, but in retrospect, of course. We knew not to mess with the Dean of Discipline. He was a real hard-ass.”

As he talked, those Journal News headlines kept strobing in my brain.

“Kevin was in our close friend group senior year, and then he just stopped hanging out with us, blamed it on having an older girlfriend. Turns out,” Bert leaned toward me and lowered his voice, “he was getting you-know-what by White.”

“Here’s another one on Stepinac. It makes one’s heart hurt,” Rita had written in her sticky note on the second article:

STEPINAC PRINCIPAL DONALD MALONE’S EXIT WAS SHROUDED IN SILENCE

According to Journal-News reporters Gary Stern and Richard Liebson, “A priest who served as principal at Archbishop Stepinac High School in White Plains was quietly removed in 1988 after police picked him up for soliciting sex from a teen-age male on a city street.”

I continued reading: “At a hastily arranged meeting between police and top officials of the Archdiocese of New York, it was decided that the matter would be dropped if the Rev. Donald T. Malone were removed from Stepinac and no longer allowed to work with youth. Malone had been arrested in 1979 under similar circumstances.”

‘It’ was decided? I stopped here to catch my breath, make connections, do the math. 1988. That’s the year Peter and I were married. 1979. That’s the year Peter graduated from this Catholic high school and Malone was promoted from Dean of Discipline to principal, the position he’d maintain for nearly a decade. And for how many years was he preying on victims before that—and after?

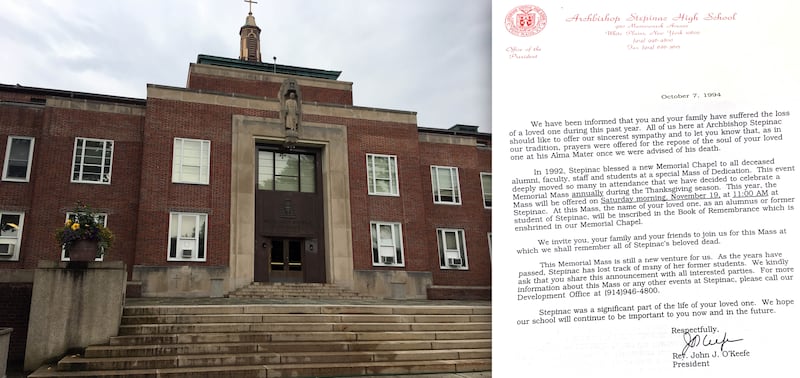

In future years of digging, I’d unearth another distressing fact reeking of complicity: Four years after Malone’s reign of terror, for 11 years starting in 1992, convicted sexual predator Monsignor John J. O’Keefe served as Stepinac’s president. In October 1994, this same pedophile signed and sent the school’s “sincerest sympathy” and “prayers offered for the repose of the soul of your loved one at his Alma Mater” condolence letter to Peter’s unsuspecting widow and four tiny offspring. They all knew.

Left: The Stepinac front steps. Right: The condolence letter sent to the author by Stepinac President, John J. O’Keefe, who would later be convicted of child abuse and defrocked.

Courtesy Jenny GrosvenorThe article confirms Bert’s recall: “The Count” walking the Stepinac hallways “in a black cape, holding a whip.” The school condoned this kind of behavior?

“The reason for Malone’s removal from Stepinac was a well-kept secret from the day it happened,” the Journal News reported, and after Malone’s arrest, “the teenager’s family did not want to press charges.”

It’s “Spotlight” all over again, I thought. The good Catholics won’t confront the priests who are like God to them. They don’t tell. And the abuse perpetuates itself.

“After he left Stepinac,” the article continued, “Malone was assigned to three parishes between 1989 and 1992.” Wait, what? Did these parishes know of Malone’s sordid history? Were the families warned? How many other boys did he groom, lure, molest—rape? “In 1993, the archdiocese put Malone on a permanent leave of absence.” Peter would be dead the next year. Had Malone heard? I’ll later wonder. Had he felt any remorse?

Journal News reporters tracked down this known pedophile priest living out his “permanent leave” at a waterfront cottage in the Hamptons, “where he has been saying mass.” He said little when confronted: “‘I’m retired,’ said Malone, looking fit and rested in a red crew neck sweater. ‘I left when my terms at Stepinac were up. Nothing more. That’s it.’”

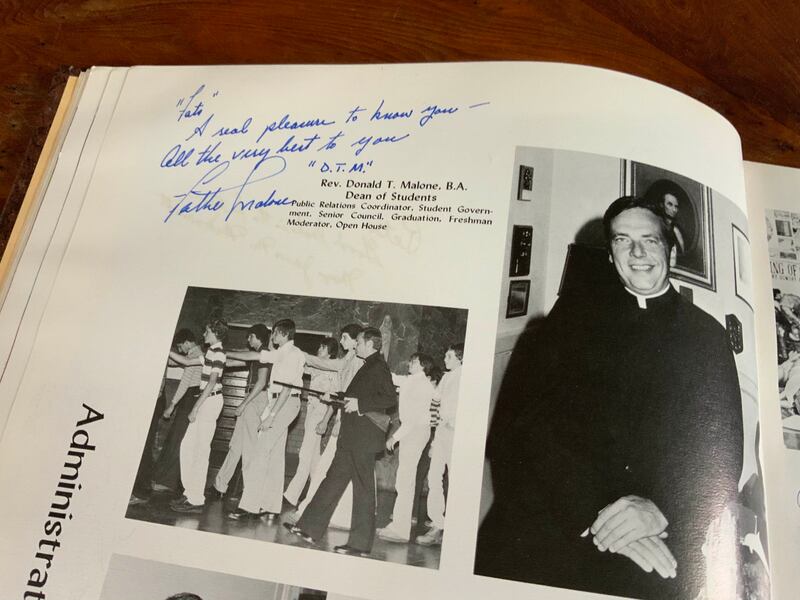

Father Donald Malone in the Stepinac yearbook.

Courtesy Jenny GrosvenorNo, that’s not it, I thought, tucking the articles back into my “Priest Abuse” folder, then peeling back the pages of Peter’s musty Shepherd ’79 yearbook. On page 18, I find him, this Rev. Donald T. Malone, B.A., Dean of Students, big smile, in priest garb, white collar and all, and the words he’d scrolled scrawled in blue ballpoint ink:

“Fats”

A real pleasure to know you—

All the best to you

“D.T.M”

Father Malone

Perplexed by the quotation marks, sickened by the familiarity of this “Father” using Peter’s nickname (simply a shortened version of his last) and insinuation in the word know, I shifted my focus to the photograph next to Malone’s smiling portrait—only to feel disturbed by the image: a group of students with heads bowed, each bearing grim faces with one arm extended forward onto the shoulder of the one in front as if a prisoners’ march. Father Malone walks alongside these boys, carrying a rifle.

“Ya really gotta see this school,” Bert said, “ya gotta, is what I’m thinking, and probably gotta try to find this Malone.”

The morning of Aug. 2, 2017, I drove solo five hours from my home in Stowe to 950 Mamaroneck Avenue, White Plains, N.Y.

In the months prior, debating whether I was daring enough to make the trip, I’d ascertained from Stepinac’s website that the current president—the ranking above principal—a Father Thomas Collins, graduated class of ’79, same as my late husband. My mind ran wild with possibilities. He would know the truth of what happened to Peter. I needed to contact him, tell him I’m coming—but what to say? Maybe the abuse by Malone happened to young Tom, too. Maybe, having been a seminarian and now in his role of power, he’s somehow complicit in this school’s history of serial priest abuse. Maybe I’d better make up another excuse for visiting—which I did: I’m writing a piece on Catholic boys schools in the Northeast… Collins did not return my email, but I managed to schedule a tour with a Patsy Manganelli. I figured, once there, foot in the door so to speak, I’d get my meeting with Father Collins.

I approached the imposing brick building holding tight to the canvas bag strapped across my pink sundress, its chrome monkey and Icelandic “Courage” medallion dangling from the zipper. I looked hard but couldn’t make out the third-floor priest residencies Bert had told me about. At the concrete steps, some colossal sculpture of a robed figure gazed down at me.

Back home in Vermont, inside the yellowed pages of that Shepherd ’79 yearbook, I’d locate its close-up on page 3 opposite the dedication and photo of Pope John Paul I, who “reigned for a mere 34 days.” The copy alongside the sculpture reads, “One Solitary Life,” stating about Jesus, “He was only 33 when the tide of public opinion turned against him.” I’d stiffened in that moment, slain by the thought, When Peter died, he was only 32.

I muscled my way through the leaded-glass doors. The ceilings inside the foyer loomed high and arched, the dark-green marble walls were spotlessly polished.

Unsure of where to find someone to direct me toward where I was supposed to be—not that I was supposed to be here—I wandered to a landing between staircases, one up, one down, stopped by a holy billboard reaching from knee-height to ceiling. My eyes followed the crosses, like a dot-to-dot, downward, reading the red-and-blue letters about Jesus Christ being the reason, the teacher “unseen but ever present,” the model, the inspiration, and the hope “for all our tomorrows.”

I snapped the first of many photographs, trying to imagine Peter as a high schooler viewing this sign during his formative years, day-in, day-out, this brainwashing.

Was Jesus Christ really their model? Whose model? Those priests’? Did this missive and “reason” give them permission to prey on young boys? What else went “unseen” in this school? And what about those victims’ “tomorrows”? What about Peter’s?

The dark hallways of the Stepinac priests’ quarters.

Courtesy Jenny GrosvenorNostalgia mitigated rage as I envisioned my late husband as a young boy amidst a bunch of classmates. There he was, mingling among peers calling him “Fats,” scurrying up and down these stairways, bumping shoulders, changing classes, fooling around, fumbling with textbooks and papers, beaming in that mischievous way of his. Peter could always make people laugh. Not a joking matter, this stealing of innocence.

“He was just here,” I was told multiple times as I stood in front of Collins’ office. My brief tour with Patsy had ended. But I wasn’t done.

Feeling caught in a game of hide and seek, curiosity unquenched, I paced in front of the elevator, then stopped. This must be the way to the priests’ quarters. I shot glances in all directions before hitting the up button, rocking back and forth before the door opened and I stepped in.

In the dark, crowded space, I couldn’t help but feel the trepidation of a young Peter on his way up to a place he doesn’t want to go. As the door slid open at the third floor, my eyes fixed on an embossed frame encasing a gold-plated portrait of Mary holding baby Jesus.

I turned right, toward a set of double doors with the warning, “Diocesan Faculty Only, Students Keep Out.”

Left: The doorway to the third-floor Stepinac priest quarters—“Diocesan Faculty Only. Students Keep Out.” Right: Inside Peter’s Stepinac yearbook, the author finds the photo of the Jesus sculpture and chapel.

Courtesy Jenny GrosvenorKeep out. Just the provocation I needed. With a twist of the doorknob, expecting it to be locked, I slipped inside.

Jesus was everywhere. Doesn’t he instill any kind of guilt or shame in these perpetrators’ souls? Or does he somehow in his own suffering way, in their sick minds, grant them permission?

My quest drove me past closed bedroom door after closed door to the end of the dark hallway, to a lit painting of the risen Lord holding one arm upward—as if to say, “Excuse me, where do you think you’re going?” From the other hand placed on his heart, beams of blue and red light streamed toward me, the words, “Jesus I Trust in You!” scrolled at his two bare feet, each dotted with blood spots from where they’d been nailed to the cross.

Despite this possible warning, I turned the corner and followed the sound of human voices, tiptoeing farther down this last, dead-end hallway. I stopped at another closed door, Room 302, shocked by the brass plate: Fr. Tom Collins.

Poet Mary Oliver whispered, “pay attention, be astonished, tell about it.”

A television blared from inside, then came a raspy cough.

Who’s in there? What might he do if he finds me here? What might he do to me if I enter his quarters?

My heart leaped, clogging my windpipe as I began reliving vicariously an inkling of the violation, the traumatization Peter—and all those other victims—must have felt. He’s in there, this so-called “Father.” But I’m paralyzed. Too afraid to step one inch closer to that door. Too petrified to knock. Spooked by Phil Saviano’s question in Spotlight: “How do you say no to God?” A suffocating sensation incapacitated me. Next second, a gut-wrenching panic propelled me to turn away, take a left at Jesus, walking briskly, cursing these strappy sandals… past the bedrooms, past the chapel, past the priests’ living and dining rooms, back to that elevator.

Why such terror?

Why am I running away from the man I came here to see?

As the elevator descended, my mind kept sprinting. How do pedophiles not think about the impact of their actions that unequivocally damage lives? Do they have consciences? How do they choose whom they’ll abuse, whose life they’ll destroy?

Here is the exhaustion in not letting go. All these years later, I keep trying, keep tunneling for answers, but there’s no bottom to it.

Back at the first-floor lobby and Collins’ office, my nerve resurfacing, I grab my phone, open email, and started typing, telling this Stepinac president I’m still here, waiting for him in the lobby. I hit send. Two seconds later comes my response: a stoplight icon and the words, Message blocked!

My hands juddered on the wheel as I drove that same afternoon in 2017 to my next planned stop before heading out to the Hamptons to find Malone: a small town in Westchester County called Crestwood, for dinner with the sisters who grew up next door to Peter—the ones who had sent me the 2002 priest-abuse articles.

“Our yards used to join each other,” Rita said as we sat down to dinner. “We’d go back and forth to each other’s houses all the time. We were like family. That’s why this split, Peter’s mother refusing to talk to any of us after her son died, was so painful.”

I’d been baffled at the time by this fissure but blamed it on the way Peter had died. The wake of suicide can wreck the closest of families.

“Our best guess, it happened because of our knowing what she knew: about the priest abuse. When we figured this piece out,” Rita said with saddened eyes, “we sort of got it, why she had cast us and so many friends out of Big Peter’s and her lives.”

My body went numb. Wait, they all knew… for how long— “And still, they couldn’t tell.” My words burst with wrath. “Look at the shame, the secrets, the denial. Look what this pedophile did to their family. To my family. To Peter’s children. All because of this awful, broken system of faith, where scum like Malone get away with it.”

“Yeah,” Rita said, “and it seems new ones who’ve abused kids get found out every day.”

More determined than ever for a showdown with Peter’s abuser, the next morning, accompanied for moral support by my good friend Lib, the ferry hopping began. Destination: Southampton. My inner trembling escalated as we left Sag Harbor, then sat in a deli parking lot along Noyack Road, rehearsing the knock on that door I’d seen in the Journal News, practicing what I’d say before pulling into the driveway at 66 Water’s Edge Road.

Father Malone’s dilapidated cottage in the Hamptons.

Courtesy Jenny GrosvenorThe yard was a mess, the house dilapidated—and empty. We decided to query a couple from across the street.

“That’s somethin’,” husband Jerry said, “all that priest stuff I’ve just been reading about. Who woulda known? And there’s so much of it now. I sure hope you find answers somehow.”

“In traumatic events, we never find the truth,” wife Gerry said, then looked deep into my eyes. “You’re brave.”

She led us to another neighbor who confirmed that Malone was dead, buried without ceremony in a simple pine box. No one had attended his funeral except a niece.

“I really don’t remember too much,” said Peter’s closest friend at Stepinac and best man in our wedding after—feeling desperate for answers—I’d tracked him down and gotten him on the phone. “But I do remember Peter telling me once how he had to deliver handkerchiefs to Malone.” Handkerchiefs? And I’m thrown: back inside that Stepinac elevator, back at that Students Keep Out sign, back amidst forbidden quarters behind that Diocesan Faculty door.

“Oh, they had their targets,” one of Peter’s fellow alums told me. “I remember him, ‘Fats’; he was one of Father Malone’s boys,” said another.

Most remain silent, and that’s what I hope can—will—change.

Home safe yet discouraged, my five-day fact-finding mission a failure—the one person, pure source of evil, who could confirm what I believed, dead—I lifted the flap of my manila envelope labeled “Abusive Priest Info.” After pausing on the photo of Peter in his red altar-boy vestments, I pawed through piles of clues to find my printed copy of Malone’s Reassignment Record. On a legal pad, I composed my own twist-of-fate compare and contrast. Such detective work—a “let me get this straight”—helped to pacify in these perpetual probing days:

1960: Malone ordained

1961: Peter is born

1961-1964: Malone appointed priest at Our Lady of Mercy; Bronx, NY

Peter is 3 years old

1965: Malone moved to Sacred Heart; Barrytown, NY

Peter is 4

1966-1970: Malone moved to St. Denis; Yonkers, NY

Peter attends grade school

1971-1988: Malone at Archbishop Stepinac High School; White Plains

1972-1979: Malone made Dean of Students at Archbishop Stepinac High School

Peter attends and graduates from Archbishop Stepinac High School

1980-1988: Malone promoted to Principal of Archbishop Stepinac High School

Peter goes to St. Michael’s College, works in New York City, falls in love, moves to Vermont, and gets married in Waitsfield, VT

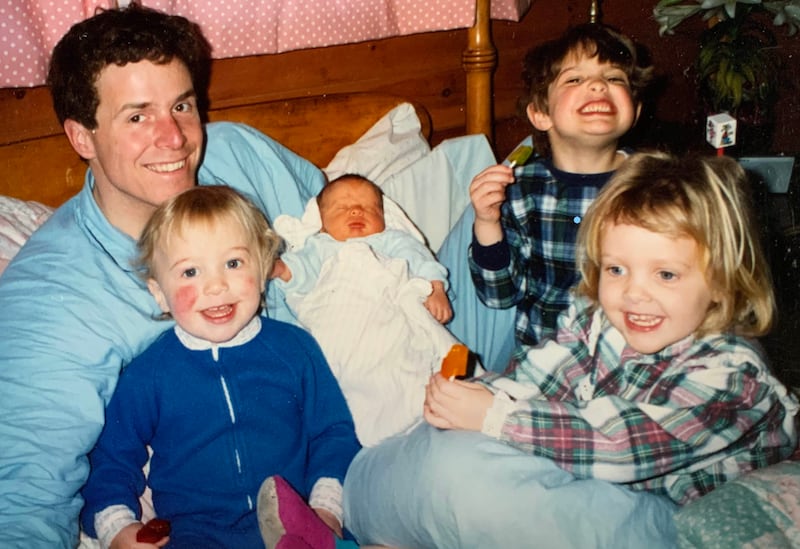

Peter on his wedding day.

Courtesy Jenny Grosvenor1989: Malone absent on sick leave

Peter’s first child, William, is born

1990: Malone moved to Blessed Sacrament; Staten Island, NY

Peter loves his job at WPTZ-TV, is happily married; his first baby boy turns 1

1991-1992: Malone absent on sick leave

Peter’s next two babies, Lillian and Sam, are born

1993: Malone made pastor at St. Patrick’s; Highland Mills, NY

Peter lives happily in Bolton Valley Ski Resort, with his wife and three babies

1994-1996: Malone not indexed in Directory

Peter’s fourth baby is born; he dies in the Huntington Gorge by suicide, is buried in Waitsfield’s Common Cemetery

The last photograph taken of Peter with all four of his children.

Courtesy Jenny Grosvenor1997-2002: Malone absent on leave

On sick leave. On sick leave. Absent on leave. How many were there, Donald?

The words of Boston Globe editor Marty Baron beat against my skull. Systemic. Manipulation. They put those same priests back into parishes time and time again. I pictured the “Spotlight” team combing through files, finding those same code words for child abuse: “on sick leave.”

On the verge of implosion, I did what I often do to release anguish, doubt, turmoil. I started to write.

Dear Father Collins,

Here is your chance to help the survivors of one of Malone’s victims.

I am desperate to vindicate Peter, somehow—for his children’s sake and for their future and the future of the Catholic Church. Peter, as you know, was such a loving, caring, fun, happy guy—right up to the three days before his tragic death. “This thing has been in me for years,” he wrote among the many words in journals left behind, “it was time to come out.” And what a horrible coming out! What a loss!

“Father” Malone has nothing to lose at this point: He’s already in hell.

Let this not be the legacy, that their dad was sexually abused by the Dean and Principal of his high school. Let the legacy be that their dad’s high school stepped forward to right an evil wrong…

I gathered every thought from scraps of paper scattered throughout the house since my return. The five-page missive composed, I copied all the faculty and trustees I could find on the Stepinac website: more than a dozen men and but one woman.

Be good, look good, don’t misbehave, chimed that inner voice instilled from childhood. You’re going to get yourself in trouble with these men—the righteous and powerful and holy. This thinking echoed a smidgen of the guilt—the shame—Peter must have borne all those years.

Finger on the touchpad, I moved the cursor to the blue Send box and let it hover until the little hand with pointer finger appeared. I paused, took a deep breath, tapped, and it was gone.

That same evening, Aug. 18, 2017, at 8:48 p.m., home alone, I received a mysterious call, 914 area code, and let it go to voicemail. “Hi Jenny, This is, uh, Father Thomas Collins,” he said, slurring his words. “I just received the email about Peter Fatovic’s wife. And there are many lies in that email, and I would like to talk to you. 914-522-0000. I hope that this will be a friendly conversation. God bless.”

The gruff voice wreaked of malice, the enunciation garbled. I felt instant fright, trauma I’d continued to battle since the beginning of my suspicions, heightened by that visit to Stepinac. In knee-jerk reaction, I rose from my desk, systematically walking from room to room, light switch by light switch, locking and double-checking every possible exterior entrance to the house. I turned the lock on the door to the garage, which I’d only done once in decades of living here—when two men had escaped from the Dannemora Prison in New York, and the news reported the convicts might have traveled to Vermont.

Will the Catholic priests come after me? I felt terrorized, again, threatened by Collins’ “many lies” accusation and the way he said, “I hope that this will be a friendly conversation.”

Three days later came the Archdiocese of New York’s blatant confession that Peter was, in fact, “abused by one of our priests.” Shortly after, I did as Cardinal Dolan’s people dictated, submitting the registration form to the Independent Reconciliation and Compensation Program (IRCP). That next day, Aug. 22, 2017, at 8 p.m., the paperwork addressed to my “DECEASED” husband from the Law Offices of K.R. Feinberg PC arrived in a FedEx envelope tucked inside my front storm door.

How to measure a life? This, the question that plagued me as I dialed the number of Camille Biros, Kenneth Feinberg’s assistant—“Ken and Camille” as they call themselves. These famous 9-11 lawyers had been hired by Dolan to make cases—hundreds of those sexually abused, names like Peter’s who’ve been on lists in hidden files, and survivors like me—go away.

Ms. Biros took my call immediately. Her voice sounded calm, respectful—devoid of emotion—as she made clear that I have every right to appeal their offer, that many people do, but nine out of 10 don’t change. She clarified that compensation is based on the impact solely on the victim—the frequency, the age of abuse, the circumstances—not on the lives of the victim’s children.

As I composed my appeal, I felt that same fury at my fingertips as when I’d written to Tom Collins.

Along with supplying copies of the children’s birth certificates, I detail Peter’s resultant loss:

· Charlie’s first smile, baptism, first tooth, first word, first roll-over, first crawl, first steps, his first birthday and every one thereafter.

· Sam’s second birthday and every one thereafter.

· Lillian’s fourth and every one thereafter.

· William’s fifth birthday, his first day of school, and every birthday thereafter.

· Turning 16, getting a driver’s license, turning 18, turning 21—all times four.

· Graduations: elementary school, middle school, high school, and college—times four.

· High school proms—times four.

· Soccer, hockey, and tennis tournaments and championships—times four.

· First Communions and Confirmations—times four.

· Family holidays—Thanksgiving and Christmas, most notably, continuing into the future.

· Future weddings and grandchildren.

This is what Donald T. Malone stole from Peter A. Fatovic, Jr. These represent a mere sampling of the milestones and priceless moments Peter lost because the Catholic Church did not protect him.

On the call, I’d asked if I would be able to tell my story should I accept the final offer. I’d read all the legal documentation but wanted to hear the answer in plain terms from the source. Biros said, “You can stand out on the street corner and scream it to the world if you like.”

The problem is, as this Camille well knows, beyond the point of settlement, almost no one tells.

In his April 8, 2019 New Yorker article “What Do the Church’s Victims Deserve?” Paul Elie explains how reconciliation and compensation programs like Cardinal Dolan’s are “rooted in the power of stories—in the human desire to know what happened and to tell others about it.” Elie concludes, “Unfortunately, the process generally stops there. The act of reckoning ends where it ought to begin.”

Sadder still, as Biros told Elie, all IRCP records would be destroyed. Stories like Peter’s. Stories, as Feinberg explained to Elie, recounted by “65-year-old men sobbing in Camille’s office… people in damaged emotional states.” Biros elaborates: “Abuse at the hands of a priest was the defining experience of the Church in their lives. Their families didn’t believe them. They find themselves questioning their sexuality, their self-worth. We see P.T.S.D. We see people who have attempted suicide.”

She fails to mention those who died by suicide.

On Christmas morning 2017, Peter’s and my grown children and I circled up by the glittering tree decorated with sacred, timeworn ornaments: ceramic bears with the words Baby 1st, 2nd, 3rd Christmas. A wooden heart with doves dangling from pink ribbons, inscribed, “Our First Christmas.” Keepsakes of the happy times.

“I need to tell you guys something,” I said, leaning closer. “It’s about your dad. I’ve been doing some serious investigating over the past nine months.” Same as with each of these four. Nine months in, nine months out, the breastfeeding birth-control method, I’d tell people. No cable on the mountain, Peter’d add with a wink. This time, my labor had birthed a dire truth.

My words fell like confetti as I told our four the story. Tears welled up in each of Peter’s grown children’s eyes.

“Wow, mom, I’m proud of you,” Will said.

And now you can be proud of your dad, too, I wanted to say but feared being too dramatic. See, he was a hero, fighting all those terrible dragons, all those years, after all.

On Sept. 8, 2018, I helped my daughter into the wedding gown she’d found at Saks Fifth Avenue, a place I used to pass daily, stopping to look, en route to and from my job in the Time-Life Building. Peter and I met at that intersection near the steps of St. Patrick’s Cathedral many post-work evenings during our romantic Manhattan days. How he’d love this dress and to see the beautiful woman his little girl has become. As I guided the zipper along her side, a home-movie clip surfaced. That 3-year-old girl claiming, “I’m gonna marry Daddy!”

Remember, Peter? Remember—

“Watch it, Mom,” Lily said.

“I know, I am,” careful not to pinch her soft skin, happy she’s brought me back into the moment, determined not to get weepy on this day.

My heart pulsated with the memory of my own wedding in Waitsfield, Vermont, 30 years prior, almost to the day. The same von Trapp granddaughter would perform two of the same songs—“Climb Every Mountain” and “Edelweiss.” Peter’s and my middle son, Sam, would officiate. Our youngest, Charlie, would read from Hilary T. Smith’s “Wild Awake”: “Love lets you find those hidden places in another person…”

Why hadn’t love helped me find Peter’s hidden places?

Wondering who would walk our daughter down the aisle someday used to bring such weighty sorrow. Something had lifted. I was both Peter in this instant and me—shoulders back, chin up, long hair clasped high on my head, silver wisps at my temples, a smile softening the wrinkles at my lips.

What a peculiar gift.

The smell of those garden roses in Lily’s bouquet lingers—untainted by the past sins of Catholic priests—as I hit play repeatedly on the 28-second video saved on my iPhone. I get teary-eyed at the lyrics, “take my hand, take my whole life, too,” where the recording stops on the moment mother and daughter embrace. I study how my arms wrap themselves, one around her neck, the other across her back. I see me holding on, a bit too tightly and too long, laugh at how I’m yanking her head backward, tugging on that long, pesky veil. I read the wise words in her eyes. My eyes. Her father’s eyes.

“Mom, you can let go now.”

I will believe these words in that magical moment—and wish I could let it go, let it be, as Peter’s brokenhearted mom kept telling me.

Truth is, I can’t. Stories surfacing daily in the news and on social media of ongoing priest abuse, the Pope’s inaction, and victims’ continuing harm and suffering won’t let me.

A Google search, using the key words “priest abuse and suicide” yields 6,720,000 results.

On April 8, 1994—four days after the birth of his youngest son and two months prior to his tragic death—for his daughter’s third birthday, for her first ski, Peter watched his little girl hobble in her small boots down our stone steps. He patiently helped her clip in. Then Daddy swooped her effortlessly from between his legs onto strong shoulders and skied down the driveway of our Bolton Valley home, disappearing onto the trail.

The next day, we—the young couple, proud parents of four—held a party for friends, family, and dozens of small children. On the home movies I watch again and again, Peter carries a large cake loaded with candles from the kitchen to a roomful of people singing “Happy Birthday” to place before his beaming daughter.

Peter with his fourth newborn, Charlie.

Courtesy Jenny GrosvenorPeter wears a white turtleneck and khakis. I look hard but don’t see a hint of unhappiness in his face or body language: not when he’s out on the deck at the grill, cooking hot dogs, feeding one to our big black dog; 19-month-old Sam sitting on top the picnic table, clapping his pudgy hands; not when he’s at our dining-room table distributing cake, posing with Lily for a father-daughter birthday shot; not when he’s joking with friends in the old-school, Jeezum Crow Vermont accent he loved to imitate; not when Will and friends are shooting him with plastic squirt guns; not when, later that night, Peter dozes in our winged-back chair with newborn Charlie sleeping curled on his shoulder.

In video after video, even in the last filming six days before his death, Peter is his calm, handsome, loving self.

In dream after dream, we are streaming down the mountain, Peter and I. He was by far the better skier, but I did my best to keep up. On one such day, I remember speeding too fast, trying to impress my fiancé. I remember a feeling of pure giddiness. Peter trailed close behind when I caught an edge and tumbled in snowball fashion. I lay there, skis and poles splayed, covered in white. Peter skied up alongside, looking concerned until I started laughing and couldn’t stop. He gave me his hand and pulled me up. I could feel the snow glazing my eyelashes as we kissed, and giggled, and kissed again.

Peter on the slopes with his “Rabbit.”

Courtesy Jenny Grosvenor“You silly Rabbit,” he said, and the name stuck.

Dear Rabbit… That’s how Peter began many an entry in the three journals we kept jointly over seven years of courtship, marriage, and parenting.

Love always to my Rabbit. That’s how Peter ended his final note.

If you or a loved one are struggling with suicidal thoughts, please reach out to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741