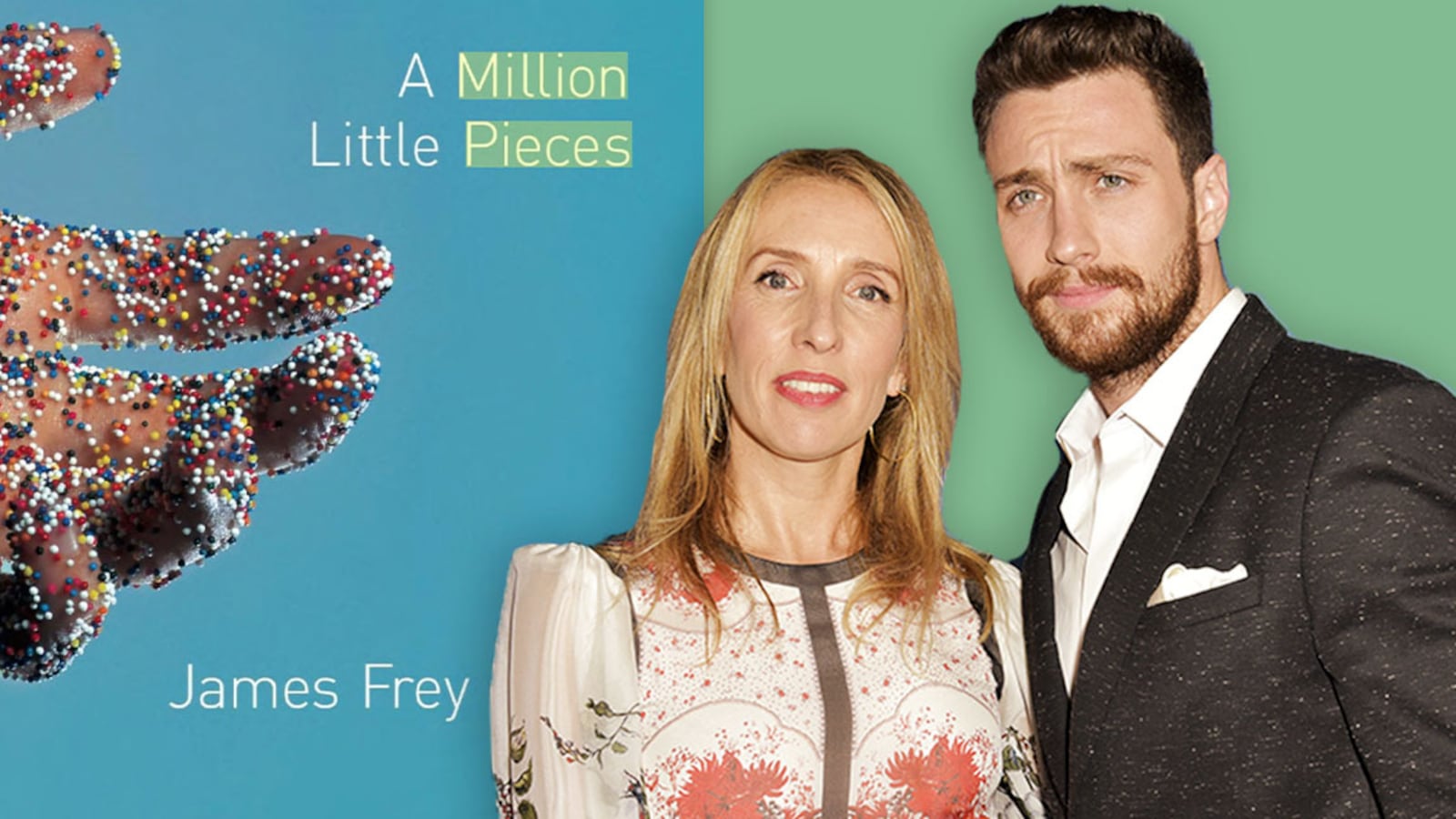

It’s hard to know where to begin when talking to Aaron and Sam Taylor-Johnson about their new film, A Million Little Pieces.

Do you start with the fact that the film, which they both wrote and produced, Sam directed, and Aaron stars in, is an adaptation of James Frey’s controversial memoir? As in the controversial memoir: the 2003 bestseller about Frey’s time as a 23-year-old addict in rehab for which, it was later found, he fabricated significant, crucial portions.

The scandal dominated headlines, culminating in Oprah Winfrey delivering him an on-air lashing, enraged to learn that after selecting the novel for her Oprah’s Book Club, she had been duped. The Taylor-Johnsons’ film is, in a talking point of its own, a direct adaptation of the memoir that does not address the forgery, outside of a Mark Twain quote that appears onscreen at the beginning: “I’ve lived through some terrible things in my life, some of which have happened.”

Alternatively, do you launch with a conversation about the couple themselves? It’s always a point of fascination when a married couple makes a film together, but the interest is undoubtedly heightened in this case because, well, the interest is always heightened in the case of Aaron and Sam Taylor-Johnson’s marriage.

He was 19 and she was 42 when they met on the set of the John Lennon biopic Nowhere Boy, which she directed in 2009. Despite their 23-year age difference, they were engaged within the year and married in 2012. They have two daughters together now, in addition to two from Sam’s previous marriage. This is the first time since meeting over a decade ago that they’ve worked together on a film.

Is it a better idea to talk about the work and the content? This intense subject matter required Aaron, who has a Golden Globe for his work in Nocturnal Animals and is known for films like Savages, Kick-Ass, and Avengers: Age of Ultron, to channel the darkness and chaos of a young man in the throes of addiction. He is completely exposed, sometimes literally: He appears fully naked several times. It’s one thing for an actor to take that on in any film production. But when the director is your own wife?

Or do you kick off the conversation with the film’s own rocky road? It premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival two festival cycles ago in fall 2018. When A Million Little Pieces hits theaters Friday, 15 months will have passed since it first showed, a year full of false starts, struggles to attain distribution, and exasperating work for the couple, who saw the shadow of the controversy surrounding Frey’s memoir routinely complicate the release of their film.

“It’s interesting when you make a movie that’s about forgiveness and how unforgiving other people can be, when on the entire journey of making this film that controversy has been a part of the fabric of making it,” Sam Taylor-Johnson says.

“We’re talking right from the very beginning about, do we want to make this despite the controversy? And then through to budgets not being too big because people are worried about it being dogged by controversy, and then through distribution deals falling through because they’re afraid of controversy, and then having to wait a year really for release because of people being nervous about the controversy. So it’s never not been there, but it’s kind of given us more grit in our belly to get it done.”

Now that the grit has taken them, finally, to actual cinemas and a theatrical release, we talk to Aaron and Sam Taylor-Johnson about all of the above. Just where to start…

In the memoir/semi-fictional novel/publishing world lightning rod—however you refer to it—A Million Little Pieces, James Frey wakes up on a flight to Chicago bruised and bloodied and with no recollection of how he ended up on the plane. When he disembarks, his family greets him and ushers him to a rehabilitation clinic. He is 23, with 10 years of alcohol addiction, three years of crack addiction, and warrants for his arrest in three states under his belt.

The cold-turkey detox is brutal. His broken nose has to be fixed and he needs a slew of painful dental work performed. But horrifyingly, he can’t take any anesthesia or pain pills for either procedure. The program is emotional torture for Frey as well. He has demons to confront that, at 23, he had only interest in retreating from.

When Oprah Winfrey gave the book her Midas endorsement, selecting it for her book club in 2005, it skyrocked to the top of the New York Times bestseller list, where it lived for 15 straight weeks.

A year later, The Smoking Gun published its investigation, “A Million Little Lies,” detailing the numerous fabrications Frey included in the book in order to sensationalize his story. Winfrey brought him back on the show along with his publisher, Nan Talese, for a lacerating interrogation, leading the Times’ David Carr to write, “Both Mr. Frey and Ms. Talese were snapped in two like dry winter twigs.”

Sam Taylor-Johnson had been wanting to turn the book into a film essentially since she first read it more than a decade ago. When she and Aaron began writing the screenplay for their adaptation, they decided very early on that, outside of the introductory Mark Twain quote, the film wouldn’t address the forgery scandal at all. The book and Frey’s journey was, in their eyes, separate from that.

“We felt that James having been through the treatment center, an addict who is 26 years sober despite everything he went through, including public humiliation and shame, stands for us and, I think, for many as a symbol of hope,” Sam says. “His crime was to embellish a memoir in the way many memoir writers have done, but he became the person, you know?”

For Aaron, the public flogging Frey endured with his sobriety intact gave him more insight into the fortitude of the 23-year-old addict version of the man. “What he went through with the book controversy and the public shaming, the fact that he is still sober to this day, there’s nothing more exposing, really.”

The preoccupation with the scandal in relation to the film they made and are now promoting is at times frustrating, but it’s certainly expected. “The journey of James is what’s important,” Sam says. “What’s important is the journey of hope and forgiveness in the world of addiction.”

You can imagine the kind of tabloid attention that ensued when the 19-year-old actor who was then Aaron Johnson and the 42-year-old director who was then Sam Taylor-Wood began dating in 2008, and then were engaged within the year, and then married a few years after that, hyphenated their last names, and started raising a family together.

It’s been over a decade since they first got together, yet we’re a culture that likes to fixate on things like an older woman with a younger man and married Hollywood power players with a 23-year age gap.

It’s something that Aaron, especially, hasn’t particularly loved talking about but has arrived at some sort of peace with, telling New York magazine in 2017, “The attention was intrusive. But having to deal with that early in my career probably got me to a place where I can more easily go, ‘Oh fuck it’ instead of wanting to rip someone’s head off.”

Sam says she knew soon after Nowhere Boy that she wanted to direct a Million Little Pieces movie and that Aaron would be great casting for it, a notion that “was sort of humming in the corner waiting for me to pick it up.” But in addition to the book’s controversy becoming a consideration before making the film, she knew working together again and embarking on a press tour would bring the fascination over their relationship back to the forefront.

“We’ve been together for over a decade now, so I feel like it is less of a conversation for people,” Sam says. “It doesn’t worry me, and it’s not something that is difficult to talk about because it’s such a positive story, that we’re a decade later together and working together and raising a strong family together. That may be a positive message for people out there.”

A husband and wife making a movie together has its own unique challenges, though, especially when the project is something as intense and dark as this one. The spouse of an actor who may tend to take on some of the weight of the role and bring it home with them is in a different position when she is the one directing that intensity and darkness. Then there’s something that any working couple can relate to: If one partner has a bad day at work, or in this case on set, going home is a respite from that. When you’re an actor and your partner is your director, and vice versa, that’s impossible.

“Luckily we don’t have that problem,” Aaron says, laughing. Shooting the entire film in 20 days on a shoestring budget, “I don’t think there was a moment to step outside of that bubble anyway.” On any given day, there were rewrites to be done, production calendars to shuffle, and money to save here in order to be spent the next day there. “It was very much that process rather than getting on each other’s nerves about something then being like, ‘Oh no, I have nowhere to go.’”

Then there’s what’s being asked of the performer in the film itself.

The first shooting day of A Million Little Pieces was to film the actual first scene: James is at rock bottom, drugged into a delirious state of consciousness at a college party, thrashing his body around violently and stripping off his clothes until he is completely naked. Bystanders watch him whirl his way to an open window, which he falls out of. Aaron lost 25 pounds for the scene and appears fully nude—as jarring an introduction as they come, both for audiences and crew members on set.

“It was a great signal to the crew for how serious we were about the movie and how raw and exposed Aaron was willing to go in order to play the role,” Sam says. Then, with a bit of a chuckle to her husband: “I think that day one was tougher on you, Aaron.”

He balks at the suggestion that he was more willing to expose himself, in every sense of the word, because of the intimacy he has with his wife, or that she was able to convince him to bare all in a way that other directors might not be able to because of their relationship.

“I’ve been completely nude and naked for Oliver Stone, for Joe Wright, for Tom Ford,” he says, dismissing the idea. “Being naked isn’t the only vulnerable feeling you can be. Acting in general, every scene you’re putting your vulnerability on the line, no matter what you’re wearing.”

He does giggle recounting that, when he and Sam initially wrote the scene, he had envisioned it taking place in a boxed room with nobody in it. It was her idea to add 10 extras to the scene, thinking witnesses to James’ madnesses would add more weight to it. As she joins in with the laughter, he adds, “It didn’t necessarily need to be in a wide shot, either.”

When all is said and done, the couple now has something that few couples can tout: a milestone in their relationship and respective lives that is both professional and personal.

They’re intrigued by that notion when it’s brought up. It’s something they hadn’t considered before. Truth be told, they haven’t had time yet to consider it. The last 15 months has been a relentless fight to get the film in theaters, with the last weeks especially a blitz of promotion.

“We haven’t had that reflective time because we had a bit of a false start after Toronto,” Sam says. “Aaron made a beautiful tree house and I got really into baking sourdough bread as a way of reflecting then. From that point, it was just going ‘OK, we’re not giving up and we will go against the odds to get this movie out there.”