The Whole Woman’s Health clinic in Fort Worth, Texas, is usually open until 5pm. Last night, like the chain’s three other locations across Texas, it was open until midnight, caring for the waiting room full of pregnant people seeking abortions before they no longer could. Outside, anti-abortion protesters camped out, shining lights in the windows as night fell and calling the police to report nonexistent violations. Inside, a doctor who had worked for the health center for decades began to cry.

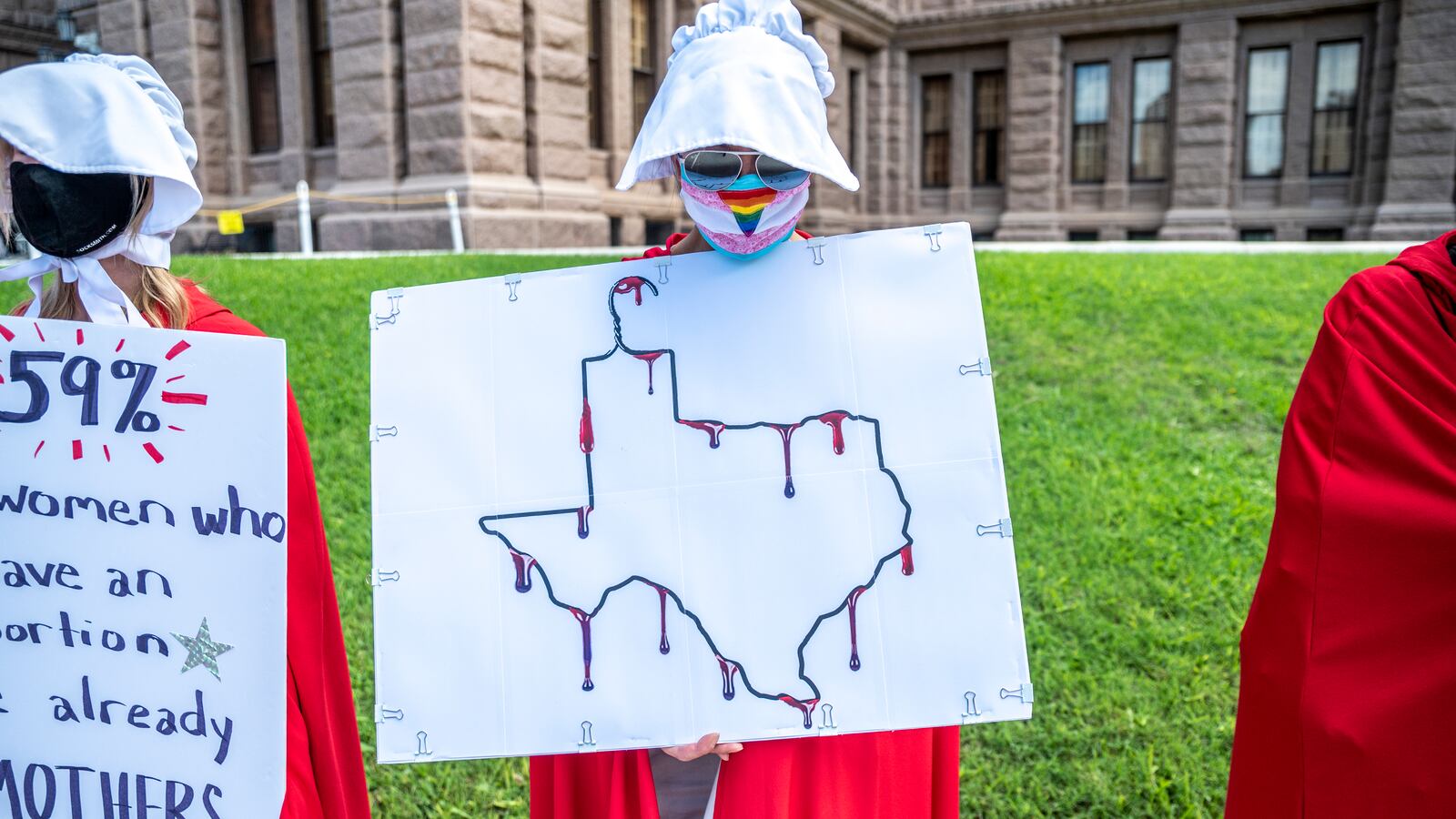

This was the scene the night before S.B. 8, a law banning abortion after six weeks of pregnancy took effect in Texas.

The law is a twist on a familiar anti-abortion tactic: Ban abortions after a “fetal heartbeat” can be detected; before most women know they are pregnant, before 85 to 90 percent of abortions in Texas take place, and ultimately erase the right to an abortion in a given state.

This is blatantly unconstitutional under existing Supreme Court precedent—Planned Parenthood v Casey prohibits all pre-viability abortion bans—which is why it has failed in the 10 other states that tried to enact it. But S.B. 8 is different. S.B. 8 takes enforcement from the hands of authorities and gives it to private citizens, allowing anyone in the state to sue anyone else suspected of providing or assisting in an abortion after six weeks’ gestation.

If that seems like a roundabout way for abortion foes to achieve their aims, the point became clear when advocates attempted to block the bill. The usual channel—filing a lawsuit against the state attorney general or other officials—was no longer available. After all, you can’t sue someone who’s not in charge of enforcing a law. You also can’t sue everyone who could potentially enforce a law—in this case, the entire state of Texas—so advocates were left to file suit against an odd coalition including the Texas Medical Board and every state court trial judge and county clerk in the state.

That suit was previously stayed in the federal district court in which it was filed and transferred to the Fifth Circuit Court, which canceled a hearing scheduled for Monday, leaving the fate of the law in limbo. Advocates filed an emergency appeal to the Supreme Court to take up the case to no avail; the Court did not hear the petition before the law took effect Wednesday morning.

At abortion clinics, that meant providing abortions in accordance with the law; conducting the state-mandated ultrasound and declining to perform the procedure if fetal cardiac activity could be detected. (Anti-abortion advocates call this a fetal heartbeat; scientists note that embryos don’t even have a heart this early in development.)

Abortion funds, meanwhile, were marshaling their resources, preparing to help pregnant people get to clinics before the cutoff or travel to another state if necessary. On Twitter, the Texas Equal Access Fund announced they’d had hundreds of volunteer applications come in just that morning.

Multiple advocates also shared links for ordering the abortion pill, which effectively terminates pregnancies before 10 weeks’ gestation. The text of S.B. 8 states that only those who provide or abet in the provision an abortion can be sued, meaning that people who self-manage their abortions with the pill or other methods may be in the clear.

But as Center for Reproductive Rights attorney Marc Hearron pointed out, no one was exactly sure: Because the law could be enforced by anyone—including private citizens without a deep understanding of the law, or even a passing knowledge of it—there was no guarantee that someone wouldn’t try to sue you for a self-managed abortion anyway. “That’s just part of the whole pernicious part of this law,” Hearron said on a press call.

Anti-abortion groups heralded the law in statements and on Twitter, but were muted on their next steps. Asked whether they believed the law could be an effective means of curtailing abortion nationally, a National Right to Life spokesperson said only that they believe “any legal strategy that saves the lives of unborn children is an effective strategy.” Steven Aden of Americans United for Life told The Daily Beast his group would be watching the court cases closely, but that for a number of reasons they did not believe the legislation would be effective outside of Texas.

The response from those leading the legal challenge to the law, meanwhile, seemed to be to wait: wait for the Supreme Court to rule, wait for the Fifth Circuit to make a decision, or wait for them to hand it back to the district court. “We are obviously not giving up, we will keep fighting,” Hearron said. But from a legal perspective, the fight seemed to be temporarily paused.

Advocates on the ground, meanwhile, promised to keep up the battle, despite what Whole Woman’s Health CEO Amy Hagstrom Miller called an “unprecedented and complicated situation.” Clinics were still open, abortion funds were still operating, and supporters were sounding the familiar drumbeat that abortion in Texas—while now much, much harder to access—was still legal.

“Our values, our commitment, and what we stand for hasn’t changed,” Hagstrom-Miller said in a press call. “Whole Woman’s Health believes abortion is a moral and social good, and we know access to safe abortion makes our communities safer and more healthy. Texans deserve better than this.”