On first blush, the movie’s premise sounds patently absurd: Abraham Lincoln, author of the Emancipation Proclamation, preserver of the Union, deliverer of the Gettysburg Address, ax-wielding killer of undead blood suckers.

And yet, the relentlessly gory 3-D thriller Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, which reaches theaters in wide release Friday, has won the vocal support of some noted Lincoln scholars who praise the film (as well as the book on which it is based) for depicting well-established but all-too-frequently ignored historical facts concerning the 16th president; namely, his Gothic worldview and explosive physicality.

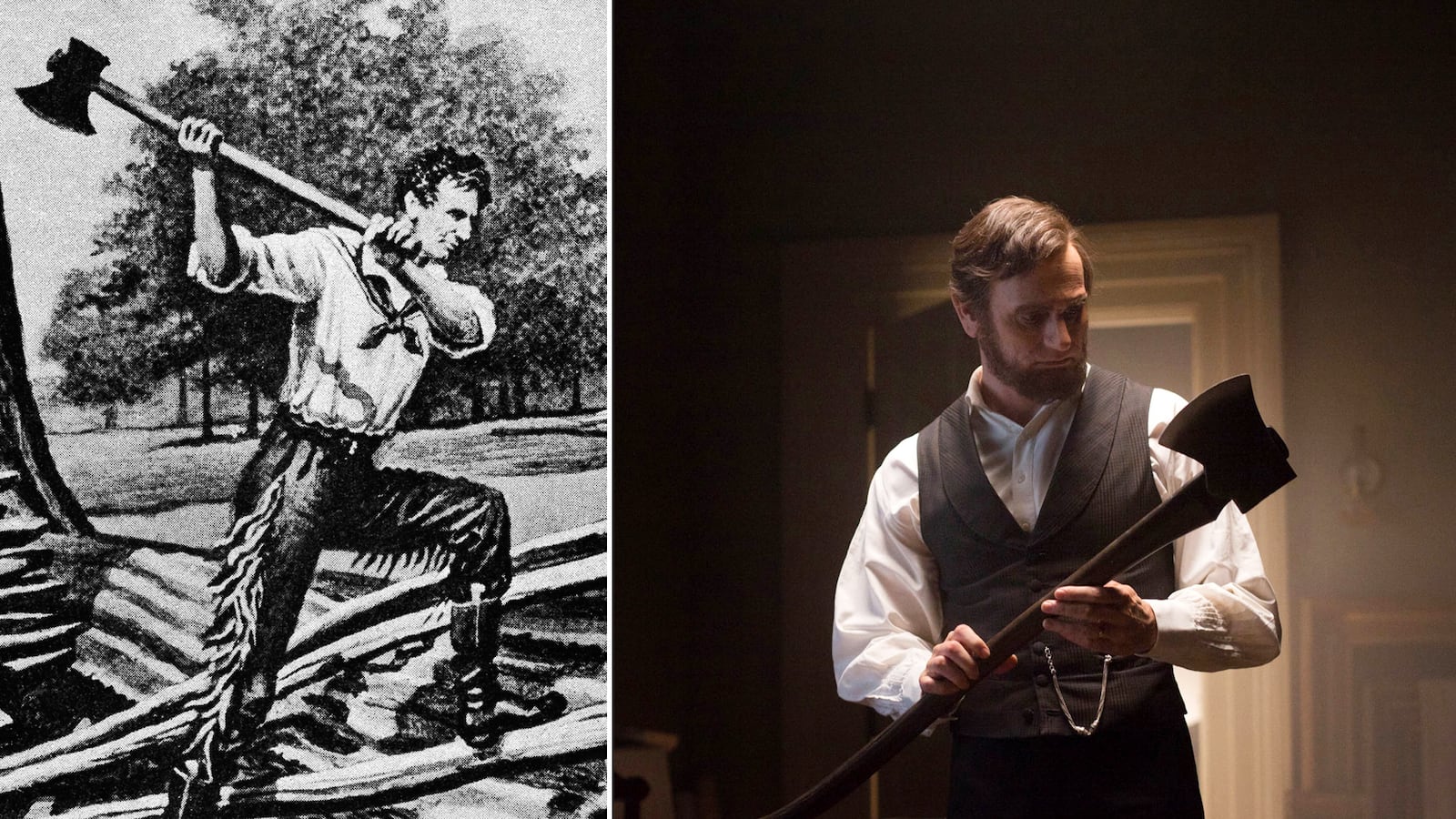

It seems that the gaunt-faced stick figure shown seated and in repose at his Washington, D.C., memorial was much more than just a man of powerful convictions, high ideals, and an even higher stovepipe hat. By many accounts, before he became commander in chief, Lincoln was a rough and ready outdoorsman, whose rail-splitter’s musculature would have been ideally suited to feats of physical daring-do. Like, say, wholesale vampire slaughter.

“I find the whole throwing of the ax at vampires to have an eerie credibility,” said noted Lincoln scholar Harold Holzer. “He could lift great weight. There was a lot of farm labor [in his upbringing], and there was a proficiency in splitting rails. He made his bones when he moved to New Salem by fighting the local bully in a wrestling match. Abraham Lincoln was a very strong guy who could use an ax.”

Contrary to whatever you may expect upon learning that both the film’s screenplay and source material were written by Seth Grahame-Smith—the “Junk Food Literature” phenom responsible for the surprise bestseller Pride and Prejudice and Zombies—Vampire Hunter stays more or less faithful to depicting the future president’s hardscrabble upbringing.

“After the age of 9, there was not a two or three period in his life when Lincoln wasn’t burying somebody,” Grahame-Smith said. “The man’s life is a 19th-century superhero story. He comes from nothing, has no education, no money, lives in the middle of nowhere on the frontier. And despite the fact that he suffers one tragedy and one setback after another, through sheer force of will, he becomes something extraordinary: not only the president but the person who almost single-handedly united the country.”

As for the book’s central creation myth: While on a 2009 book tour in support of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (a literary genre mash-up of Jane Austen and George A. Romero that is also scheduled to be adapted into a film), Grahame-Smith visited bookstores from coast to coast where he would invariably encounter two display racks: one featuring stacks of Lincoln biographies, in celebration of the president’s birth bicentennial, another piled with titles from the Twilight vampire romance series.

Somewhere along the line, Grahame-Smith had a your-chocolate’s-in-my-peanut-butter moment. “It was this weird confrontation of these two delicious flavors that got me consciously or subconsciously combining Lincoln and vampires as an observational in-joke with myself,” he said.

The writer put himself on a crash course in Lincoln lore, devouring Honest Abe’s collected writings and a mini-library’s worth of biographies in an effort to bring verisimilitude to the project–one, it should be noted, that recasts the president as a ninja-like assassin hell-bent on massacring creatures of the night as payback for deep-seeded personal pain. In the book, an evil blood-sucker kills Lincoln’s mother, and the Great Emancipator’s dawning political consciousness comes as a direct result of his interactions with nefarious vampire slave owners. “Before I deconstructed it in a genre way, I wanted to interweave as much history as possible,” former freelancer and TV writer Grahame-Smith said. “That was the fun of it for me, to make it so close to his actual life, it would give you pause to question what was real.”

But on the way to what seemed like an all but inevitable backlash by Lincoln purists, reality took a left turn. Both the book and film manage to tap into Lincoln’s widely documented penchant for the macabre, the maudlin, and the Gothic. A fanatic for Shakespeare’s plays, the 16th president devoted Edgar Allan Poe’s prose to memory (the writer even makes a cameo in the movie). And Lincoln recited Scottish poet William Knox’s meditation on death, “Mortality,” so frequently, many of Lincoln’s contemporaries mistakenly credited him as its author.

The upshot? Doris Kearns Goodwin, author of the bestselling Lincoln history Team of Rivals big-upped the book on National Public Radio. Grahame-Smith was invited to the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Ill.—twice—where the writer was introduced the state historian and allowed to hold one of five known copies of the Gettysburg Address. And more than a few respected Lincoln experts expressed slightly shocked admiration.

“He’s a really good writer and created a believable plot,” Holzer said. “Parts were so credibly formulated, one fear I had was that people would believe the conceit.”

Compelled by Grahame-Smith’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies hotness quotient, in 2009 director-producer Tim Burton contacted the writer and ended up optioning the rights to adapt Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter before a completed draft of the book had been finished. The Dark Shadows auteur says it reminded him of “weird” early-’70s genre mash-up movies—such as Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde—that he grew up with and helped shape his aesthetic.

Burton elaborated on his fascination with the Lincoln-as-fearless-vampire-killer concept to The Daily Beast: “Just look at the guy. He just looked like he’d been up all night hunting vampires! It makes weird sense.”

Of course, not all Lincoln scholars cherish such a reimagining of America’s 16th president. Founding director of the Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum Richard Norton Smith called Vampire Hunter “the most inane idea imaginable” and “a true bastardization of the Lincoln story” in an email to The Daily Beast.

And there certainly exists no historical documentation to establish that—as the movie lays out—Honest Abe ever leap-frogged from horseback to horseback during a stampede, jumped from a speeding locomotive while the wooden bridge upon which it had run exploded in flame or ever carried through a single decapitation (let alone a multiple head-hack with a single ax swing).

But as Holzer sees it, Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter functions most effectively on a metaphorical level.

“Vampirism is a metaphor for slavery,” he said. “It’s a metaphor for an evil that is almost incomprehensible—that such a brutal, inhuman thing was allowed to exist and grow generationally. He had a metaphorical objective. I tip my hat to the guy.”

“It’s not the intent of the book or movie to take blame off the human slave owners, but the parallels are obvious,” agreed Grahame-Smith. “Both steal life blood to enrich themselves. Both are inherently evil. Both use fear as a means of controlling other people. In those ways, vampires are just like slave owners.”