BELLINZONA, Switzerland—Allegations of rape, killing, and cannibalism made the man an outlaw who victims say roared like a lion before striking his prey, and yet the chances were that he would outrun justice.

A quarter-century after his alleged crimes, Alieu Kosiah is now in a European detention facility awaiting a decision on his fate, facing up to 20 years in prison.

Kosiah fled recriminations at home and was living a new life in picturesque Switzerland, one of the world’s wealthiest nations, when officials finally apprehended him.

He is accused of multiple murders and serial rapes back in Liberia, West Africa. The trial came to life thanks to seven plaintiffs, six of whom traveled to Europe to face the man they say once terrorized them. The seventh victim, whom The Daily Beast is calling Teta, alleges she was kidnapped and raped by Kosiah, who she says removed a rifle slung across his shoulder and pulled a knife from his belt before he repeatedly violated her.

Teta, who gave birth to a premature baby during the trial, provided evidence via videolink from Monrovia, as the child was too fragile to travel. The court asked Teta how she felt towards Kosiah all these years later. She feared him, she said, and buried her head in her hands. “He’s a killer and rapist,” she said. The judge asked if she was waiting for an apology. “I can’t accept his apologies,” she replied. On a subsequent call, when asked how she found the courage to testify despite her trepidation, she told The Daily Beast, “I want justice. He should be judged; he should be tried.”

Even once he was arrested—after some two decades of living peacefully in Europe—the prospect of this trial seemed remote. Evidence in such a case is hard to pull together when crime scenes have been destroyed, and witnesses are long since dead. But Swiss prosecutors eventually indicted Kosiah after five years of criminal investigations.

According to lawyers for the plaintiffs, the case is monumental because it represents many firsts in the fight toward accountability for crimes committed in Liberia’s back-to-back civil wars from 1989-2003. “It’s the first war crimes trial for sexual violence [in Liberia], for child soldiers, the first time a Liberian will be convicted or acquitted for war crimes, and the first time there will be a judgment for war crimes in front of the Swiss Federal Criminal Court,” Alain Werner, a Swiss lawyer representing several victims in the case, told The Daily Beast. The court is expected to issue a verdict next month.

One of the witnesses, a tall man in his fifties wearing a striped polo shirt and jeans, said he watched as a close friend’s chest was sliced open before his heart was removed and served to rebels, including Kosiah, on a metal plate.

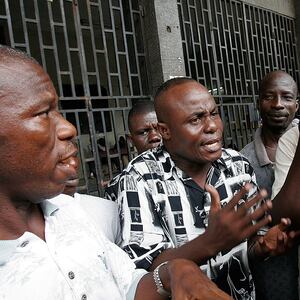

This man, whose name is withheld to protect him from reprisal when he returns home to Lofa County in northern Liberia, told the Daily Beast that it was breathtaking to face Kosiah again in the flesh. “When you see him, it’s all you can do not to…” he said, as his voice trailed off. “You can’t imagine the brutality.”

It was 1994, early in the rainy season, and the then 15-year-old Teta was tending to her family’s rice crops when the fighters arrived in her remote village in Lofa County. The war was raging, and members of the ULIMO faction had come to overtake the area from Charles Taylor’s group. The fighters took some of the men, including Teta’s father and brother, to the town center, where they tied their arms behind their back until their elbows touched. They ordered the women to cook for them and gathered all the rice and oil in the village; Teta fetched water and cleaned the dishes. The rebels, Teta observed, responded to a superior named “General Kosiah.” The General, who was 19, commanded the civilians to form a convoy to transport goods and ammunition, likely toward the Guinean border.

Teta thought only of her survival, and when she saw an opportunity, she fled into the bush. She later made her way to the town center, where she’d last seen her father and brother, only to find them slaughtered. For several days, she hid in the bush without food. When the hunger had sucked the life out of her, she ventured to a nearby village to replenish herself. She noticed a group of rebels smoking and chatting in front of a house. A small boy, whose gun dragged behind his body, approached. “Come,” she recalled him saying. “If you don’t come, I will kill you. It’s the General that’s calling you.”

Teta says she followed the boy to the General, the same one she’d seen days earlier in her village, named Kosiah. He wore military clothing, his eyes were bulbous, and his skin was darker than hers, Teta noticed. “You will be my wife,” she recalled him saying. Teta says she was ordered into a nearby house and locked in the bedroom. That night, she says, he returned and took off his boots, clothes, and weapons. Teta claims he then took her body for himself, raping her every few hours. His body splayed on top of hers, and when she cried, she says he threatened to kill her. The following day, when the door was left unlocked, Teta escaped. She was naked, had no shoes, and while she’d never menstruated before, she was bleeding. Kosiah denies the charges.

Sexual violence during Liberia’s back-to-back civil wars was endemic. The true scale is still unknown. The International Committee of the Red Cross estimated that over 70 percent of sexual-based violations were perpetrated against women and girls, who were used as “bush wives” and domestic servants, among other abuses. Still, more than 15 years since the conflicts concluded and took the lives of an estimated 250,000 people, civil war-era sexual violations carry a deep stigma, shrouded in a culture of shame.

“The impunity for war crimes, in general, had an impact on ongoing impunity for crimes of sexual violence in Liberia,” said Emmanuelle Marchand, the head of the legal unit at Civitas Maxima, a Swiss-based organization that investigates war crimes in Liberia. “Liberia is still a country where violence against women is integrated,” Marchand told The Daily Beast.

In 2009, Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission released a report recommending establishing a special war crimes tribunal. Still, Liberia has yet to hold a single perpetrator responsible for atrocities committed during its two civil wars. Some well-known warlords have taken up high-level government positions, and others have resettled in third countries, building families and businesses. The few cases involving war crimes have occurred in third country courts, in the U.S. and Europe, where perpetrators were found living.

Kosiah, a former ULIMO commander who Teta said raped her, is now at the center of the first war crimes trial for atrocities committed during Liberia’s first civil war.

In February, six Liberian men traveled thousands of miles by plane from Monrovia to Geneva and then by train to a tranquil Italian-speaking town in the Swiss alps called Bellinzona, near the Italian border. They stayed in a modest hotel in the historic town center, where rice was hard to come by, but pizza was in abundance. Some had never seen the snow and found the cold biting. Each was there as a complainant to testify before a panel of three Swiss judges at the Federal Criminal Court about their allegations against Kosiah. The seventh complainant and only woman, Teta, whose name has been changed for her safety, appeared by video stream from the U.S. embassy in Monrovia. She had given birth just days before. The fact the complainants had made it this far was a feat in itself.

In 2013, Alain Werner, the Swiss lawyer who runs Civitas Maxima, an organization investigating crimes on behalf of Liberian victims to prosecute perpetrators in national courts, received a tip: a former ULIMO commander was living near Lake Geneva. Werner had never heard of Kosiah, but given the ULIMO’s extensively documented crimes committed in Lofa County between 1993 and 1995, he was confident there would be a case. Werner called their sister organization in Monrovia, the Global Justice and Research Project, whose investigators started digging.

“It could have been that we got the name [Kosiah], we did the investigation on the ground, and nobody heard about it. In this case, that didn’t happen,” Werner said. “We got the name. We did an investigation. Crimes came back,” he told The Daily Beast. In the summer of 2014, Werner and partner lawyers filed a criminal complaint against Kosiah on behalf of seven Liberian victims. Swiss authorities arrested Kosiah in November that year, and he has been in pre-trial detention since.

Much of the material evidence was damaged or destroyed following the first civil war, and key witnesses were killed or since died. Some witnesses feared retribution and refused to participate in the trial. Then, a global pandemic prevented willing victims and witnesses from traveling. When, finally, the logistics were in place, the Swiss courtroom held the hearing at reduced capacity. The complainants, their four lawyers, and two Swiss prosecutors sat at a distance with masks. Kosiah, who is now 46, sat slumped at the front of the room, wearing a white-collared shirt and casual jacket. His lawyer, Dimitri Gianoli, accompanied him.

On the first day of hearings, a man, Mr. S, who grew up in Zorzor, in Lofa county, took the stand. He had a soft, round face and wore a collared shirt under a padded jacket. “Kosiah ordered a girl to be carried to his house,” he said. “If he called, you had no option but to follow. You could not refuse him,” the man, who would have been 15 at the time, told the court. For Werner, the strength of the case lies in victims corroborating patterns of crimes across Lofa County. “Kosiah randomly took a woman to rape her, and the woman managed to escape, in a completely different town [from Teta], miles away,” Werner said.

At some point, Kosiah abruptly stood up and erupted in shouting. “It’s been six years,” he said, referring to his time in detention. “He lied,” as he pointed to Mr. S., who began trembling. Mr. S. took a break in the courtroom hallway, convening with other plaintiffs. “He’s very rude,” one man said of Kosiah, who had been shuffling through stacks of paper, elbowing his lawyer and whispering into his ear as the plaintiffs testified.

Others who took the stand said they were certain Kosiah was the same person who committed the alleged crimes more than two decades earlier—they recognized his bulging eyes, his dark skin, and his anger. One was a former child soldier who, at the age of 12, said Kosiah had recruited him as his personal bodyguard; another said he saw Kosiah order his brother’s execution; and another said Kosiah and his men desecrated the corpse of a civilian and ate his heart.

Between 1993 and 1995, Kosiah was a commander with the ULIMO-K as it took control of much of Lofa county, which became the site of gruesome and debased attacks against civilians.

As the conflict ravaged Liberia in the early ’90s, the NPFL had targeted members of the Krahn and Mandingo ethnic groups, whom they saw as sympathizing with Samuel Doe’s government. According to news reports, Kosiah, then a teenager, had escaped to neighboring Sierra Leone when his family members were viciously murdered. There, Kosiah joined ULIMO-K, a Mandingo-based faction that took up arms against Taylor’s group, and rose through its ranks to become a commander.

According to Swiss prosecutors, during this period, Kosiah violated the laws of war by committing rape, recruiting and using child soldiers, ordering pillages and forced transports, murdering civilians, and committing acts of cannibalism.

When, in 1997, Taylor was elected president and the first war concluded, Kosiah fled to Switzerland, where he applied for asylum, claiming to be Guinean. His application was denied, but he later obtained permanent residence through his wife, who lived in the beautiful, mountainous canton of Vaud. The trial was made possible by a 2011 Swiss law that allows the prosecution of non-nationals who committed serious international crimes on foreign soil, also known as the principle of universal jurisdiction. The case is the first war crimes trial to occur outside of a military court in Switzerland; it is also the first, anywhere in the world, to adjudicate rape as a war crime in Liberia, setting a meaningful precedent. (The trials against Mohammed Jabbateh and Chuckie Taylor, the son of Charles, in the U.S., addressed rape during the war in the context of charges for immigration fraud and torture, respectively.)

Kosiah claims he is not guilty of any such crimes, as he was not present in Lofa County during the relevant period. He also says that witnesses and victims of these crimes are conspiring against him and lying. Kosiah’s lawyer did not respond to requests for an interview.

Teta’s lawyer, Zeina Wakim, flew to Monrovia from Geneva to accompany her on the day she took the stand from the embassy in the second week of hearings. The Swiss ambassador traveled from Abidjan, in Côte d’Ivoire, to ensure the process went smoothly; embassy officials were present, as were Swiss federal police. Teta, whose face is striking, wore a bright orange blouse and long braids. She described to the court, in thick Liberian English, that she had never been educated but that she recognized Kosiah. “It’s him who’s looking at the camera. I know him too good,” she said.

After she escaped the house where she said Kosiah raped her, Teta crawled into the bush, following a road toward Guinea. She bled for three days and slept under tree roots to shield herself from the rain. She planted seeds along the way, telling people that if her mother came looking, she could find her in Guinea. Teta made it across the border and cooked for a local family who, in exchange, allowed her to sleep on their kitchen floor. Her mother, by some miracle, got word. She, too, ventured into Guinea, traveling from village to village, searching for Teta. A year or so later, they reunited. More than a decade passed, and when they heard a woman, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, became president in Liberia, they went home.

Teta told me she still suffers physical pain and “feels bad” when she puts her mind back to the war. Today, Teta takes care of her mother, who is elderly, and her children, who taught her English. She is happiest when she’s outside farming rice, pepper, and cassava. On Sundays, she rests and attends church. The event that most occupies her time these days is caring for her baby girl, so tiny that Wakim thought they might lose her during the court procedure. Once the baby is strong enough, she’ll carry her as she farms. The baby, she said, she named Justice.