The first person the U.S. government ever detained indefinitely under the 2001 Patriot Act has gone free.

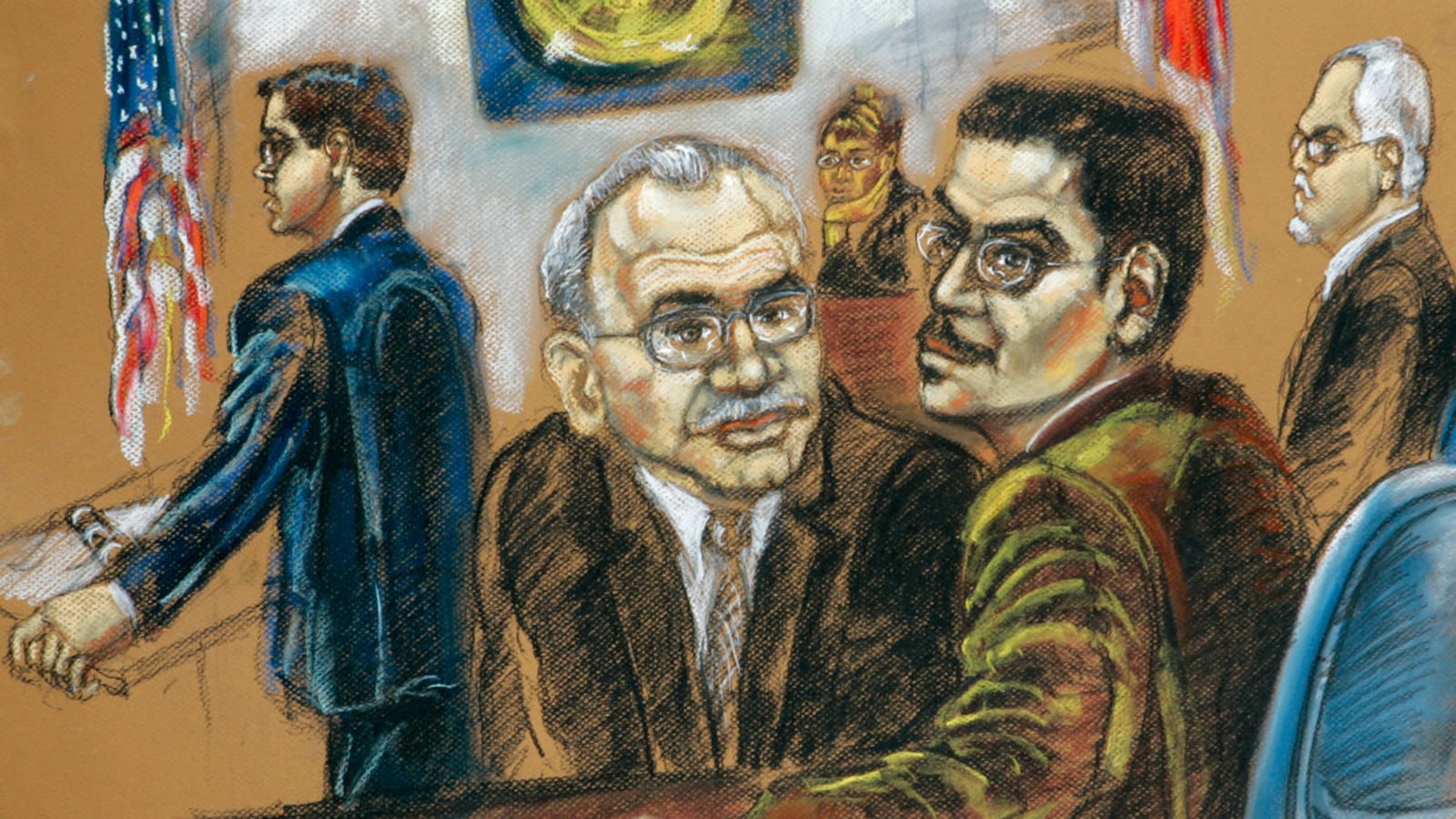

Adham Amin Hassoun, whose Kafkaesque experience during the 9/11 era turned him into the U.S.’ first post-conviction terrorism detainee, has left the U.S. for an unnamed country, his lawyers said.

After Hassoun’s conviction expired in 2017, the Department of Homeland Security and the Justice Department had sought unreviewable authority to detain Hassoun under both an obscure immigration regulation and a never-before invoked provision of the Patriot Act, known as Section 412. The administration declared Hassoun, a man in his late 50s who has never been accused of violence, a threat to national security.

But in response to a case challenging the government to charge or release Hassoun, a federal judge last month ruled that the administration had to provide evidence and witnesses for its assertions and permit Hassoun’s attorneys to challenge them. Instead, the Justice Department conceded that it could not meet that standard—one found in every American criminal courtroom.

At first, the administration appealed Judge Elizabeth Wolford’s order for Hassoun to be released into the custody of his sister in Florida. But in an indication of the unlikelihood of its success, it arranged his departure from the country—something it had for years said was impossible for the Palestinian national—before exhausting its appellate avenues.

“This isn’t going to determine the constitutionality of PATRIOT Section 412, but what it does do is show precisely why the government can’t have the authority to detain someone indefinitely without launching criminal charges,” said Nicole Hallett, one of Hassoun’s lawyers.

It’s an astonishing resolution for a man whom the Bush administration first criminalized, also under the Patriot Act, on charges of material support for terrorism. After keeping Hassoun in immigration detention while the FBI pressed him to become an informant, it accused him of sending money to terror cells. At sentencing, the judge in Hassoun’s case pointedly noted that the Justice Department could not point to any act of violence Hassoun enabled or facilitated.

Hassoun completed his sentence in October 2017. But instead of releasing him, the government sought to deport him. When it couldn’t find a country willing to accept the stateless Hassoun, it sent him into an ICE prison outside Buffalo, New York, making him a pioneer of the Forever War: the first terrorism convict it detained after his time was served.

To do so, it labeled Hassoun a threat to the country based on a jailhouse snitch whose account Wolford exposed as so unreliable that it prompted the judge to consider sanctioning the Justice Department.

“If the government has this authority, it will abuse it,” attorney Hallett said, “and that has been proven in this case.”