Ronald Poppo had found a good hiding spot: a rarely used stairwell of a parking lot near the Jungle Island zoo, a Miami tourist attraction on Watson Island, right off the MacArthur Causeway. Under the steps, where it was dark and cool, the 65-year-old built a nest for himself on the damp cement floor, on a bed of flattened cardboard. It was a kind of man-made cave, walled by unpainted cinderblock, eight feet wide. In one corner, Poppo kept water and some rags for washing up. In another, he kept his cans of food and a couple of utensils. Nearby, at a dock, were public toilets.

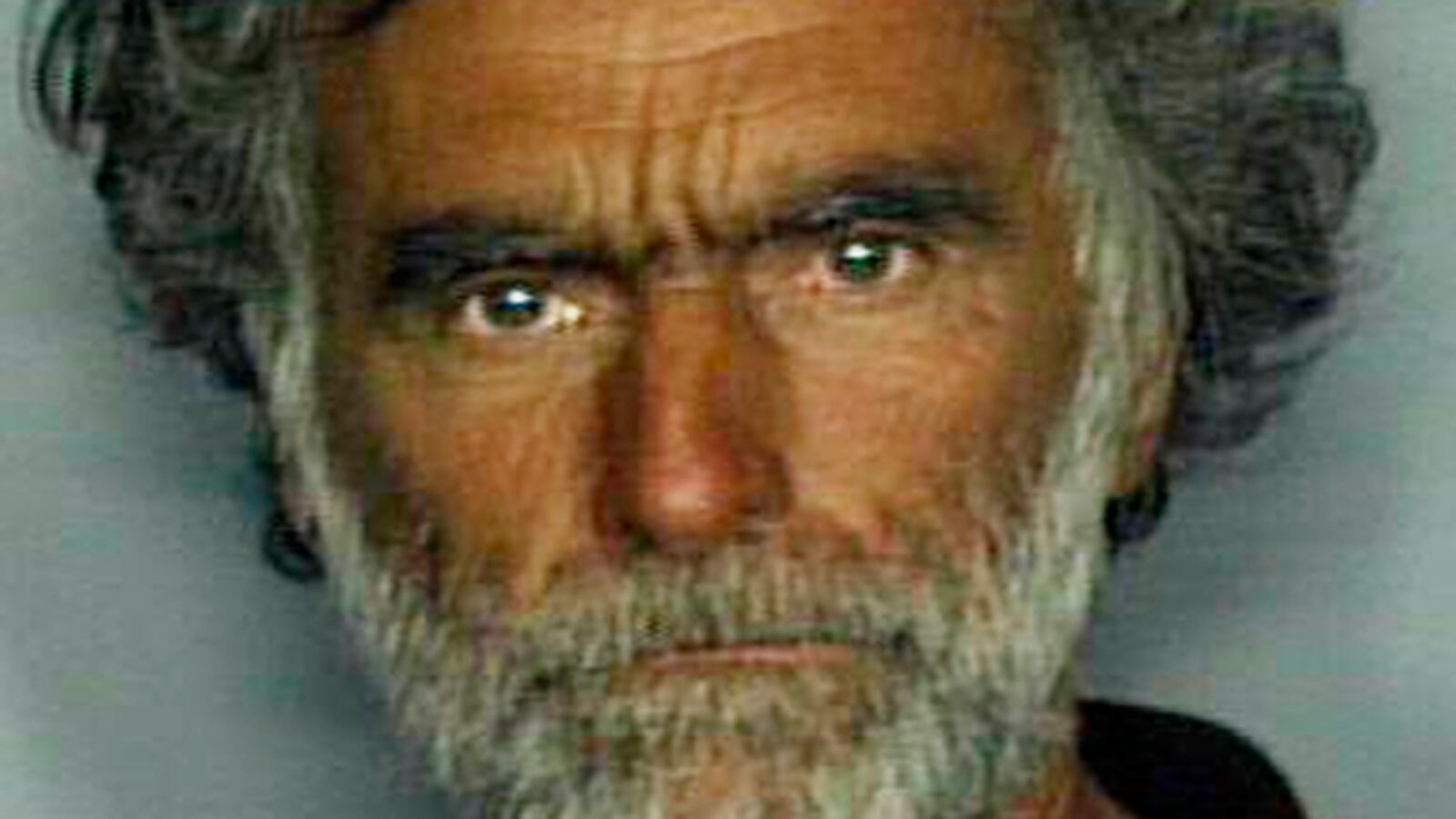

From here it’s only a mile walk along the causeway to the place where, on May 26, Poppo was attacked in broad daylight, in one of the most gruesome crimes in recent memory. Most of his face was bitten off by a naked man suspected of using powerful drugs.

Poppo is being cared for at the Ryder Trauma Center at Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami. In the days since the assault, some details have emerged of his life in the days and months before.

As a teenager in the 1960s, Poppo attended New York City’s elite Stuyvesant public high school, but he later drifted into the anonymity of alcoholism and homelessness. Poppo’s sister lost touch with him 40 years ago, CBS Miami reported, and his own daughter didn’t know he was alive, according to the New York Daily News. Few people knew Poppo, and fewer cared about him.

But two men who work for Miami’s Homeless Assistance Program did know him and did care. In an exclusive interview, the two city workers showed The Daily Beast the stairwell where Poppo spent his nights and said they tried to bring him into the city’s shelter system.

“I told him, ‘You could be my grandpa!’” said Jairo Mesa, one of the men. “It breaks my heart.”

Mesa’s partner is 29-year-old Giancarlo Venturini. With two years’ experience at this job, he’s an old hand; Mesa, 38, has worked with the homeless for only four months. Every day, the two men, part of a 25-person outreach force, scour the streets looking for people everyone else wants to ignore.

“We have to search them out,” Venturini said. “Most people, they feel sorry for them, so they try to not even see them. Or sometimes they’re afraid: ‘If I don’t look at them, they aren’t going to see me.’ But it’s our job.”

The story Venturini and Mesa told about Poppo reveals new facets of a man who hid in plain sight for decades, who made the choice to live a secret life on the miserable street.

Ronald Book, the head of Miami-Dade’s Homeless Trust, which helps coordinate and fund Miami’s homeless programs, said Poppo was one of the region’s “chronically” homeless. At last count, he said, there were about 270 such cases in Miami.

“Look,” he said, “we had a bed for that guy. We had a place for him to go. He could have come off the street. The guy wanted to be in the street.”

The city’s outreach workers first came across Poppo in 1999, when he was 52. During one period, in 2004, Book said, Poppo briefly took advantage of the city services, which include medical care, shelter, job referrals, and social work, but he fell off the grid again that same year.

Poppo reappeared about a month ago, Venturini said. He and Mesa came across the aging homeless man when the Jungle Island tourist attraction complained of a bum in a café who was scaring patrons. Mesa and Venturini headed out in their big white van and found Poppo lying down in his stairwell home. He appeared to be in the throes of a monster hangover, they said, and he was just mean. “The first time,” recalled Venturini, “he just looked like a regular guy who had too many beers.”

They told him he was trespassing and that there had been complaints. They offered him a bed, a shower, doctors. But he angered fast, yelling aggressively at them. They headed outside to call a police officer, and Poppo followed them out into the sunlight. At the time, they didn’t even know his name.

He raised his hands and wiggled his fingers at them. “Death to both of you!” he shouted. “He was, like, putting a gypsy curse on us,” Venturini recalled. “He was yelling at the top of his lungs.”

Poppo kept trying to spit at them, but was so dehydrated from his drinking, he couldn’t get any saliva out. “Fuck you!” he shouted. “Fuck you. Fuck you. Fuck you!”

Then he shuffled off.

The team and the staff gathered up Poppo’s encampment. “It was a little mansion here,” Venturini said. “He had his kitchen here. His washroom here.”

But the management of the site wanted him out.

“We grabbed his stuff,” Venturini said, “made sure there was no identification papers he would need and no medication. There was food you can eat without being cooked and then water, lots of water, so he could bathe. He had rags so he could clean himself; he had utensils. I don’t recall any books. I think maybe he had a radio.”

It all went into a Dumpster. A few days later, the team drove by again to find that Poppo had pulled everything from the trash and set himself up in the very same spot. Once again, they dismantled his little home, but this time they trucked it off to throw it away, so Poppo couldn’t find it.

For days, Venturini and Mesa drove by, looking for Poppo. He’d disappeared.

Then about a week later, as a storm was approaching Miami, they visited again and found him on the second floor of his stairwell.

Poppo had changed dramatically. He hadn’t shaved, and his hair was wild. And yet, somewhere he had found a nice-looking gray suit jacket. “He looked like Grizzly Adams,” recalled Venturini, “but he had a nice jacket on.”

“He liked that jacket,” Mesa said.

This time, though he was disheveled, Poppo was polite and well spoken.

“What’s your name?” he asked. “I said, ‘Ronald, you don’t remember me?’” Mesa said.

“Oh, you’re Mesa!” Poppo replied.

The two men urged him to come with them. Mesa, friendly with a light Cuban accent, pleaded with him: “I said, ‘You can be my father, you can be my grandpa.’ That’s what I told him. I have a heart, you know. That’s why I have this job.”

They could see that the old man’s calves were darkened with some kind of skin infection from scratching bug bites. “It’s a common thing with homeless people,” Venturini said. “His legs kind of looked … not like leprosy, but they were scabby.” He needed peroxide.

The wind was blowing outside that night, and the rain was coming down. But the workers pointed out to Poppo that he was still trespassing.

“I’m going to walk,” Poppo told the two workers, and he stood up. “I’m going to walk.”

Once again the aging homeless man left, into the night, heading out into the dark storm in his gray suit jacket, ragged pants, and flip-flop sandals.

The last time they saw him was Thursday, May 24, around 9:30 in the evening. They had driven by to look for him and caught a glimpse of him walking past the parking garage on the grass on his way to the stairwell. It’s a lush spot near the zoo, with a huge stone statue of a big-bellied Buddha.

Poppo, moving quickly along, was wearing his gray jacket and carrying the flattened box. “All he had was some cardboard,” Venturini said. They whipped their van around to talk to him. They found a police officer and asked him to come along.

Poppo got to a bus station, where, he may have figured, he couldn’t be accused of trespassing. He was angry and started cursing.

“Go bother those motherfuckers down there, man!” He pointed down the causeway and used a racial epithet. “Down there!”

The police officer gave him a paper warning about trespassing. And then Poppo shuffled away again, carrying his flattened cardboard so no one would steal it.

“Believe it or not, you get robbed a lot when you’re homeless,” Venturini said. “You’ve got nothing. You’ve got your little bag, but this guy next to you doesn’t have anything at all, and he wants to take yours.”

Mesa and Venturini said they knew Poppo would head back to the parking lot stairwell again that night to sleep.

But soon, he must have walked that mile along the causeway, over the water back to Miami. Overhead was a giant poster advertising Apple’s new iPad.

It was less than 36 hours after Mesa and Venturini saw him that that Poppo was brutally attacked, along the same causeway under the iPad poster and near the Miami Herald building. Nearby is a stoplight that’s a popular spot for panhandlers to approach motorists.

The savagery lasted 18 minutes, and it only ended when a police officer put multiple rounds into the big naked man, Rudy Eugene, who was biting off pieces of Poppo’s face.

Police recently released some of the 911 calls.

"He's going to kill that man, I promise you," said a bus driver watching the attack.

Venturini had been off that weekend, and he heard about what happened a few days layer. “I heard it from my roommate, and he’s like: ‘This guy got eaten by a zombie or something.’ I’m like: ‘What are you talking about?’”

Soon he and Mesa realized who it was.

The dark space where Poppo lived is now empty, and the ground is damp, but on the second floor, where he stayed in recent weeks, there is still some cardboard from a case of Heineken, held down by a rock. A wire coat hanger is hooked to the handrail.

Under the causeway a man sat near the spot where Poppo was savaged. He said his name was Ricky Davies, and he had a cardboard sign next to him that said, “Please help me, I need work.” He wore a faded shirt saying “Fish You Were Here.” His sneakers were drying a few feet away after a heavy rain. Asked where he lived, he said, “Right here.” He said he hadn’t heard of the attack on the homeless man 100 yards away.