This is a critical movement for American workers as unions, already on their heels in the age of Trump, are reeling after the Supreme Court’s Janus decision this week. Organized labor has been in decline for decades, but it’s not dead yet. The ruling could force the movement to return to its roots, and perhaps even find a better path forward.

Even as private-sector unions have declined, public-sector ones have grown in their own right and as a share of the organized labor movement since 1977’s Supreme Court decision, ABOOD V. Detroit Board of Education allowed them to require non-members to pay an “agency fee” for the benefits unions negotiated on their behalf. This meant no one was compelled to join a union or to pay for its political activities, while also protecting those public-sector unions from free-riders, who’d prefer not to pay at all even as they benefit from unions’ bargaining efforts.

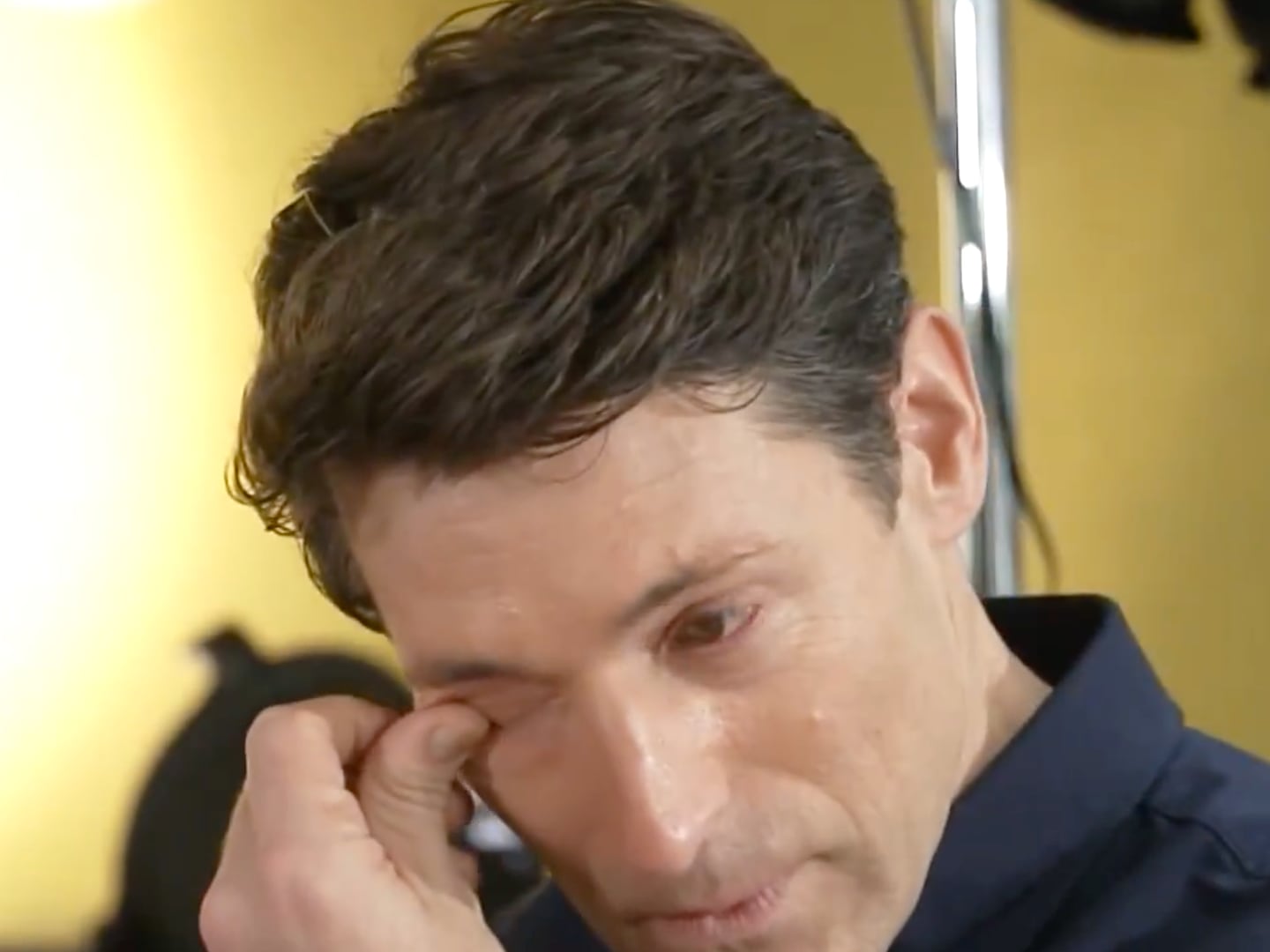

Janus, named for Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services employee Mark Janus, who objected to the agency fees as a violation of his free speech rights, ended that. Five justices ruled that public unions “may no longer extract agency fees from nonconsenting employees … The procedure violates the First Amendment and cannot continue.”

One recent report estimates that the decision will lead to a loss of 726,000 union members—reducing public unions’ ability to bargain effectively and bring cases to arbitration. In the long-run, the study predicts an overall 3.6% decline in public-sector wages, and a 5.4% drop in the wages of public-school teachers.

This seems dire, or rather, a dire continuation of the decline of organized labor in the private sector since the late 1970s. Labor scholars, such as Vanderbilt’s Jefferson Cowie and Georgetown’s Joseph McCartin, have written about this decline’s political origin and impact. Union membership is now at an all-time low, at 10.7% of total workforce—down by half since 1983. Today, there are five times more public sector members than private-sector ones, which makes a large-scale decline in public unionism that much amplified.

Laws and the courts have alway mattered for labor in America, as unions have fought for better laws and fairer rules even as they organized workers. Employers, better organized and bankrolled than workers, have long resorted to using courts to stymie labor, according to legal scholar Christopher Tomlins. In the 19th and the early 20th centuries, a prefered tool was the “yellow dog contract,” which many workers were forced to sign as a condition of employment. It stated that if they joined a union they would be fired.

Author Kristen Downey and others have shown how the New Deal and specifically the 1935 Wagner Act reversed the hostile legal environment and established a more moderate and level field of regulations. But those national gains were rolled back in some states just 12 years later with the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act, which updated and curtailed some aspects of the Wagner Act and allowed states to pass what became known as right-to-work laws. Twenty-eight states have now passed such laws forbidding so-called union security agreements, or closed shops, in which employers agree to only hire union-members and employees must remain members of the union.

Wagner and Taft-Hartley did not cover public-sector union relations, which were relatively rare then. That changed in 1962, when President John F. Kennedy issued Executive Order No 10998, which granted federal workers the right to join unions and led to what can only be called an explosion in public-sector union membership.

That explosion helped the union movement compensate for a nearly four-decade long decline, dating back to the Reagan years and the pulling back of New Deal-era worker protections, in private-sector unions, which now cover just 7% of workers — the lowest share since 1932.

The Janus decision — based on an expansive view of the first amendment broadened arguments laid out in Citizens United — slams the brakes on public-sector unionism. In a dissent she read from the bench, Justice Elena Kagan warned that the decision was “weaponizing the First Amendment in a way that unleashes judges, now and in the future, to intervene in economic and regulatory policy.” That appears likely, and still more so with Justice Kennedy’s retirement poised to shift the balance of the court.

So this is indeed a dire moment for what remains of organized labor, as the percentage of employees in unions, already at a low-water mark, is poised to sink even lower. But there are signs that labor organizers and workers organizing themselves are starting to develop the necessary strategies for a revival.

Recent and massive teachers strikes in right-to-work states from Arizona to West Virginia seemed to come out of nowhere. Teachers were self-organized, often seeming to catch their unions by surprise. And they went viral, forcing even anti-union governors to bargain with their workers. The teachers combined old-style worker self-activity, or grass-roots organizing, with the new techniques of social media creating a model that other groups can emulate.

And the aftermath of another recent Supreme Court ruling that anticipated Janus also points to the road forward for what remains of organized labor. In the 2014 case of Harris V. Quinn, an Illinois home healthcare worker, represented by Service Employees International Union, sued the state claiming that the law requiring her to pay fair share or agency dues injured her free speech. The Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in her favor. Sound familiar?

The short-term effects on the union representing home health care workers, the United Domestic Workers of America, bear out what the above mentioned report predicted for the aftermath of Janus. The union saw an immediate decline, from 68,000 members to 48,000. Today, however, that union has 75,000 members. Harris didn’t kill them.

The court decision forced UDW to develop new strategies. The union used a newly designed app and social media to connect to their scattered and isolated workforce, and pressed hard to prove to workers that the union’s value to them went well beyond bargaining over wages into workplace protections and to the creation of what amounted to a union employment bureau or job registry to help members find jobs.

UDW had to make the case for labor as a larger social institution. And here they found their power. Workers in the early 20th century had no protections, and that was the reason unions were born and grew. Nowhere is this as clear as with garment workers in New York City. Working in scattered, small shops and divided by ethnic and language barriers, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union found their strength in workers communities. They advocated for fair housing, fought high food costs, created summer camps for workers, provided health care and education for members. They created worlds in which workers found friends, family and strength. The bounds of the social gave the union strength. This model of social unionism died with the austerity programs of the mid-1970s and Reagan’s assault on labor, but its success should be remembered.

The roots of the American labor movement are not in the realm of narrow economic bargaining nor does it need to rely solely on the state for success. Unions were forced into that mold because of the regulatory state created by New Deal liberals’ paternalistic view of workers and business fear of unions. Unions narrowed their scope and practices and stopped being a social movement rooted in community, and became this more narrow bureaucratic, economic institution. One can say that this strategy contained them and restrained them. It was, however, not without its benefits as workers in the 1950s and 1960s did exceptionally well and most gladly accepted the bargain. But, this purely economic or bread-and-butter focus took them further away from their communities, which were always a source of strength and left them flat-footed when the landscape changed.

Jefferson Cowie from Vanderbilt has argued that part of our problem stems from an incorrect reading of history. We see our current landscape as an exception and the period 1935-1980 as normal. He argues that the New Deal era is a great exception to American history. Therefore, using the tools and practices developed during the New Deal in our current time will no longer work. Instead, we need to rediscover the tools from the past and remake them for the future.

Janus could be a blessing in disguise if it forces the labor movement to break free of a narrow economic vision and its too-close alliance with the Democratic Party, and hastens a return to its social movement roots.

The labor movement is now at a crossroads. It can cling to what now seems to be a failed strategy rooted in an exceptional period, or return to basics and working-class communities.