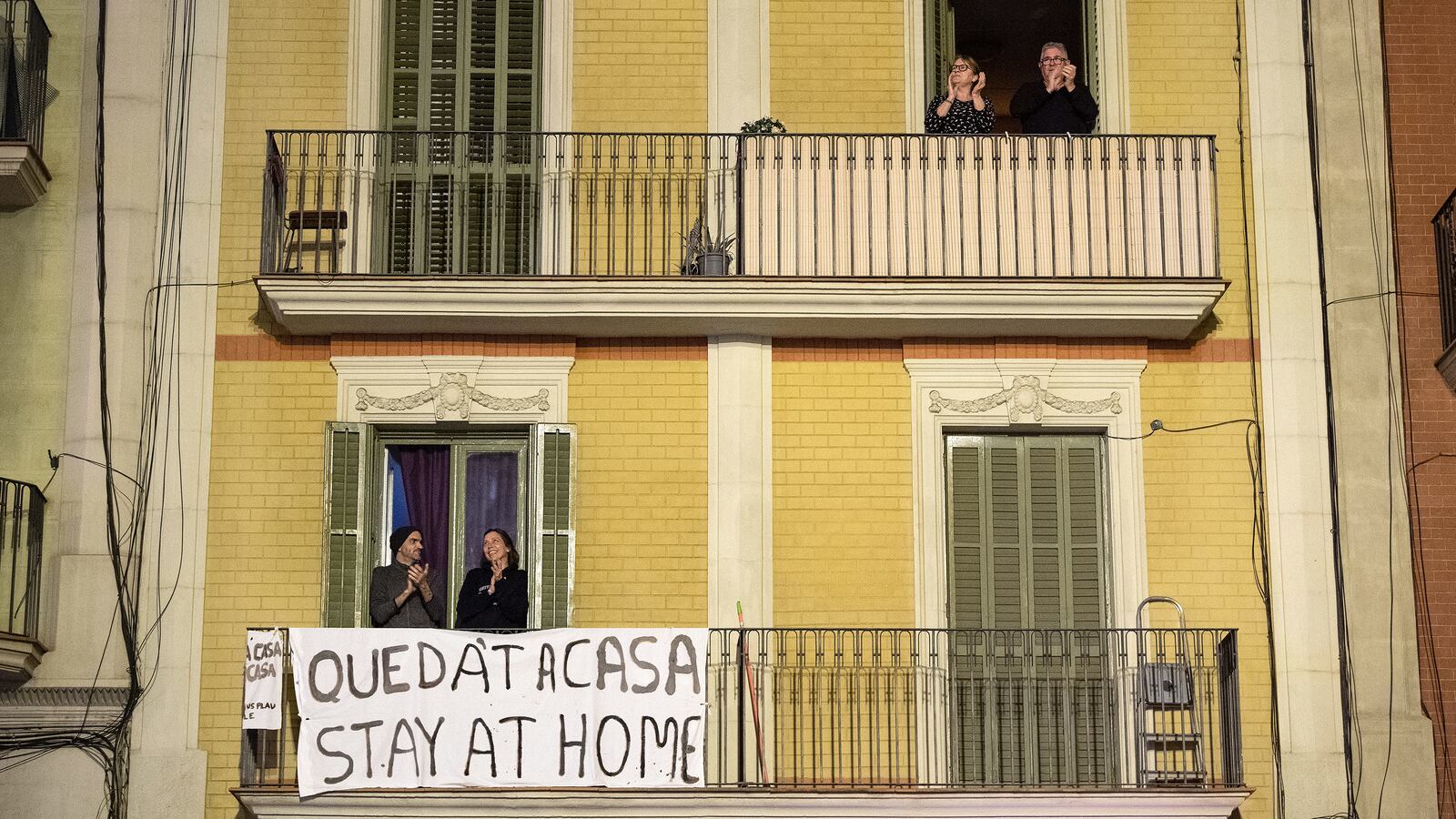

BARCELONA—Good Friday in Spain marks nearly a month of a general coronavirus lockdown. Villages in the south of Spain that normally would welcome tourists for the Semana Santa holiday are now shuttered. Some have opted to erect barricades to keep outsiders out.

In Italy quarantines have been in place even longer. Entire communities remain traumatized by legions of the dying and the dead, some of whom have been carted off unceremoniously in military vehicles. Europe remains paralyzed by COVID-19 despite having public health systems that are far more robust than those in the developing world or, for that matter, the United States.

Obviously the continent cannot remain forever under lock and key. A quick look at a map of air traffic over Europe says a lot about how the virus has impacted the social fabric. Skies that once were filled with travelers are for the most part empty.

The euro currency zone’s third- and fourth-largest economies, Italy and Spain, are set to shrink by more than 10 percent. Germany, the European Union’s economic powerhouse, could shrink by the same amount, which would have a knock-on effect across the continent. In total, the economic damage makes the great recession of 2009, when the Eurozone GDP shrank by 4.5 percent, look like a veritable bull market.

Europeans have watched Asia’s response to the epidemic closely and with concern. The virus is storming to life in Singapore and Japan, which once believed they had it under control. More worrying still, traditional tracing measures may not be capturing all those carrying the virus. In three hotspots, including Tokyo, “They have seen a number of cases that can’t be linked to chains of transmission,” says Michael J. Ryan, executive director of the World Health Organization’s emergencies program.

While everyone recognizes the immediate need to get life back to normal in Europe, experts warn that a quick end to quarantines would certainly only add fuel to the fire.

“Lifting restrictions too quickly could lead to a deadly resurgence,” says WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. He warns that the virus already has tested Europe’s sturdy health care infrastructure to its very limit. It would almost certainly be overwhelmed if Europe decided tomorrow that it is open for business, and that leaves the continent’s political leaders having to choose their poison.

“This will probably be a bit like walking the tightrope,” says Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen of Denmark, which is set to open schools and daycare centers on April 15. “If we stand still along the way we could fall and if we go too fast it can go wrong. Therefore, we must take one cautious step at a time."

Both Austria and Denmark plan to lift restrictions in gradual increments. Austria’s mom and pop shops are expected to reopen April 14, while larger stores are scheduled to reopen in early May. Mandatory masks, social distancing, and limitations on the number of people allowed into a store at any one time will remain in force. If all goes well, public events may begin again some time in July.

Sounds like a simple plan, but in fact it’s high risk. “As soon as you lift restrictions you run the risk for rapid transition into the epidemic once again,” says Lauren Meyers, a mathematical biologist and professor of integrative biology at the University of Texas at Austin. “You basically go back to day one where you have a virus that is attacking a population that is not immune and still has the same capacity to spread.”

Finding the best way to lift a quarantine is immensely complicated. The virus is new, which means there is little information about the ability of society to develop “herd immunity,” or the percentage of the population who are asymptomatic carriers, or the likelihood of finding a vaccine early. Lockdowns and isolation are meant to slow the pace of the coronavirus, they do not stop it.

Experts attempting to model the impact of the virus say there could be more trouble ahead. “Should we consider or not second or third waves in the pandemic—a pattern clearly arising in most if not all the simulations,” asks Xavier Rodo an epidemiological modeler at The Barcelona Institute for Global Health, “or presume that we will have an effective treatment in the coming few months or a vaccine, or that we will have the capacity to track every single case and its contacts to make effective quarantines, or even if the virus will seasonally fade?”

At Italy’s Istituto Superiore di Sanità in Rome, epidemiologist Flavia Riccardo believes that it is still too early to tell if the plague will become endemic like, say, the measles. And as we continue to learn about COVID-19 the known unknowns, to borrow a phrase, will tend to define what the “new normal” looks like in Europe.

Homes for the elderly will need to be reformed, for instance, perhaps limiting the number of residents, requiring more in the way of medical facilities, and strictly limiting the number of visitors. Travel and movement, large gatherings—concerts, football matches—are out for the foreseeable future.

First on the list is having a much better idea of who has the virus and where. “There is a big push towards having better and more extensive testing availability,” Riccardo told The Beast. “With better testing we can monitor the disease including the number of people who may have antibodies. We can have better mechanisms for isolation and quarantine.”

The theory goes that at a minimum any move away from quarantine requires enough control so that hospitals and other medical facilities have the capacity to deal with any surge in patients that may result from the lifting of restrictions.

But for the most part, Europe still does not have the large scale testing capacity to fully understand where the virus is or who exactly is infected. Countries like Spain and Italy, the hardest hit by the virus, only now have enough personal protection equipment in hospitals and among frontline health workers. Calculations will have to be made as to how much more is necessary to ensure that the health system stays afloat.

Even within Europe the approaches to lifting quarantine will vary with the landscape. Countries with more rural populations may be able to lift quarantine faster than those with heavily urban populations. Poorer, denser cities which are more subject to contagion may be among the last to begin to let down their guard. Governments will have to make calculations taking into consideration such issues as how many people live in an average dwelling.

“Barcelona may reduce quarantine in a different way than Madrid,” says Carlos del Rio, chair of Emory University’s Department of Global Health. “They are going to have to know how extensive the disease is. They are going to have to know who in the population is affected.”

Cafe culture, frequent flying, sports, even walking down a street without fear of contagion is a reality Europe can only hope to resume, and for now the question is not just when, but if.