The Iranian president's outrageous claims about 9/11 were the latest in a game he plays with the media. Hooman Majd on how we miss his real message amid the furor. His new book, The Ayatollah's Democracy, is available now.

When President Ahmadinejad spoke at the U.N. General Assembly on Thursday, the Israeli delegation was absent, the U.S. walked out on him, and we were once again willing and unwilling witnesses to the yearly Ahmadinejad show, for the sixth time in five years, no less.

The Ahmadinejad circus actually rolled into town last weekend, and you'd think the media might have figured out by now, one, what questions to ask him, and two, that he isn't, to use George Bush's term, the "decider" when it comes to the questions that they do ask him. Over the five days leading up to his speech, Ahmadinejad answered essentially the same few questions posed to him by different television personalities and print journalists, so many times, in fact, that at one point in one TV interview he even prompted the interviewer's next question, saying "I know that it's there in your list of questions to ask."

The American hikers jailed by Iran (and one released), the Holocaust, Israel, and anti-Semitism, the human-rights situation in Iran (and stoning of women), and, of course, the nuclear issue are, for all intents and purposes, all that America wants to know. Hikers? "Not my area of responsibility, but maybe the U.S. could release some Iranians, you know?" was Ahmadinejad's uniform response. Holocaust? "Why are you so sensitive to this question, and who perpetuated it anyway, the Palestinians?" We've heard that on almost every occasion he's been interviewed, ever since he questioned the veracity of that tragic story. Stoning? "Fuggedaboutit—never was going to happen, anyway, pure propaganda, and not my area of responsibility." Freedom in Iran? "Everyone is free to do or say as they wish in Iran." Nuclear issue and sanctions? "Sanctions aren't going to work, and we're ready to negotiate if we are respected."

Ahmadinejad can be frustrating to question or interview, but he can occasionally be witty, too, as when, at a breakfast meeting for the media that I attended, he responded to a question about Iran's reaction to the U.S. $60 billion arms sale to Saudi Arabia, saying that it was another indicator of America being a "peace-loving" nation.

Inviting the U.N. to set up an independent fact-finding group for 9/11 was even kookier, but I suppose one might be thankful that he didn't propose that he and Chavez head it.

• Stephen Kinzer: My Dinner with AhmadinejadThe circus can be interesting and even amusing, but what matters most about Ahmadinejad's visits to the Big Apple is his address to the U.N. It is here, after all, that he puts forward not only his personal views or agenda (which he does, in contrast to previous Iranian presidents and dignitaries who always stayed on message, meaning that of the supreme leader's, when representing Iran to the world), but what it is that Iran thinks and wants when it comes to points of disagreement and conflict with the U.N. and some of its member countries. And this year, like every other time he has addressed the world body, one had to suffer through Ahmadinejad's own particular views on the demise of something—this year it was capitalism, the reasons for its demise mainly because, "Man's disconnection from Heaven detached him from his true self"—before getting to the meaty parts of his speech. But wait. This year, the Iranian president, perhaps feeling he hadn't quite riled up Americans as much as he wanted to, or as he had in past years, with Holocaust-denial now old news and new controversies wanting, seemingly decided to discuss the one thing guaranteed to get a rise from an American audience: the 9/11 attacks.

It did, in fact, get a literal rise, for the few U.S. delegates listening to his speech rose from their seats and walked out. In past years, most of the U.S. delegation walked out just as he began his address, leaving a junior staffer to take note, but this year, surprisingly, given the low point in relations between the two countries, a number of U.S. diplomats stayed to listen to Ahmadinejad's now obligatory "Waiting for Mahdi" introduction and presumably would have afforded the Iranian president the respect of listening to his entire address had he not brought up 9/11. It wasn't that he brought it up, it was that he questioned what actually happened. Now, he may have just been watching too many 9/11 conspiracy-theory movies on YouTube, but his declaration on the theory that the U.S. government orchestrated the attacks "to reverse the declining American economy and its grip on the Middle East in order to save the Zionist regime" is the "majority view of the American people as well as other nations and politicians" was just kooky enough to make one question if he really believed what he was saying. And inviting the U.N. to set up an independent fact-finding group for 9/11 was even kookier, but I suppose one might be thankful that he didn't propose that he and Hugo Chavez head it.

I have to admit to being surprised that the part of speech he devoted to Israel/Palestine was shorter and milder in tone than usual, but it followed hot on the heels of his 9/11-denial, and perhaps for once he thought that even he might sometimes go overboard. Blaming the "Zionist regime" for crimes and suggesting that "solutions are doomed to fail (meaning the Obama-led peace negotiations) because "the right of the Palestinian people is not taken into account" is about as mild as Mahmoud Ahmadinejad can get on the issue, milder even than in his media appearances this trip.

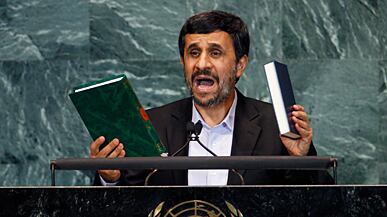

Ahmadinejad got to nuclear energy finally in his self-described analysis of the "current governance of the world." But before he addressed the specific subject of Iran's program, he decided he would criticize Koran-burning, holding in his hands a copy of the Koran and the Bible, saying that Iran respects "all divine books and their followers." Although it was somewhat surprising that he would mention Koran burning at all, given how insignificant it was, I was more surprised that he said "the truth could not be burned" and he didn't suggest, as he had done before, that it was a "Zionist conspiracy." But, I guess, he must've wondered just how many different conspiracies can one reveal in one speech?

In his discussing of the nuclear issue (and the sideways criticism of the Security Council and the right of veto of the five permanent members), Ahmadinejad was merely voicing Iran's longstanding positions: that it would not be bullied into submission, that it would abide by IAEA regulations but go no further, and was "ready for dialogue on the issue (with the U.S.) based on respect and justice." Very little of what Ahmadinejad said on Iran's nuclear program would be disputed by most Iranians, not even leaders of the Green Movement back in Tehran. Very little would be disputed by others in the world, particularly the developing world, but also in America, where few want to see armed conflict break out between the U.S. and Iran.

It's a pity that Ahmadinejad's words (or Iran's words, really) on the nuclear program; the unfairness of sanctions resolutions and depriving Iran of its rights, and Iran's offer to negotiate, will essentially go unnoticed because of Ahmadinejad's (and these were his) words on 9/11 conspiracies. The U.S. will no doubt refer to Iran's defiance on the nuclear issue, which is to be expected, but this year, Ahmadinejad's 9/11-denial will be what will be remembered about the U.N. General Assembly. Sadly, it does neither Iran nor the U.S. any good, and Ahmadinejad, who after five trips to New York still does not understand America, is squarely to blame for that.

Hooman Majd served as an adviser and translator for two Iranian presidents, Mohammad Khatami and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, on their trips to the U.S. and the U.N. He is the author of The Ayatollah Begs to Differ and is based in New York.