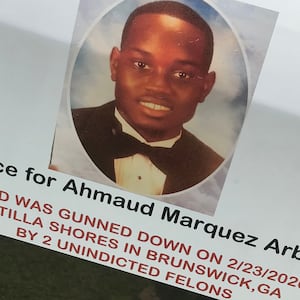

The trial of three men charged in the killing of Ahmaud Arbery is slated to begin in October. But if a Georgia Superior Court judge grants a series of requests made by attorneys for the defense, it will be Arbery who goes on trial.

Lawyers for Gregory and Travis McMichael—the father and son, respectively, who chased down Arbery in their pickup truck before fatally shooting him three times at close range—filed a motion late last year requesting that Judge Timothy Walmsley permit only one photo of Arbery “when living” to be shown during the trial, that he be depicted alone and not in the company of loved ones, and that he be identified to the court during trial by a non-family member. In the filing, the defense team argues that to allow more photos would potentially create “the danger of unfair prejudice” among jurors.

The McMichaels’ lawyers have also filed a motion asking that prosecutors be barred from referring to Arbery as a “victim” for the same reasons. “The purpose of this motion is to prevent the prosecution from ignoring its duty to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that crimes were actually committed and that [the] McMichaels committed the crimes as charged,” the defense motion states. The filing goes on to note that the McMichaels do “not concede that criminal conduct occurred in this case,” and that “the use of loaded words,” such as identifying Arbery as a “victim,” tacitly ascribes guilt to the McMichaels, denying them the presumption of innocence.

These are the tactics of a defense team attempting to justify the white vigilante killing of Arbery, who can no longer speak for himself, by framing it into an act of self defense. Cellphone footage—shot by third defendant and ambush participant William “Roddie” Bryan—clearly documents the armed vehicular pursuit of Arbery by his attackers, capturing the horrific moment when Travis McMichael fired off the shotgun blasts that killed the 25-year-old Arbery. In the face of that unequivocal evidence, the McMichaels and Bryan have nonetheless entered “not guilty” pleas to the nine charges they each face: four counts of felony murder, two counts of aggravated assault, malice murder, false imprisonment, and criminal intent to commit false imprisonment. In recent months, their lawyers have filed an ever-growing mountain of motions to prevent a jury from seeing the human life his killers snuffed out that day. Instead, defense lawyers are working to portray a young man who was jogging near his home as a dangerous Black threat whose death was warranted and even necessary.

The legal team’s strategy for getting a jury to agree is to make Arbery, who was unarmed and on foot when armed white men in pickup trucks gave chase, into a criminal threat to white society. At a July hearing, Kevin Gough, a defense lawyer for Bryan, suggested that Arbery was attempting a carjacking. “Whether he intends to take the vehicle, push Mr. Bryan out or bury him in the woods, we don’t know,” Gough said to the court. “But a jury can reasonably infer that Mr. Arbery was trying to commit a felony.”

In multiple motions and responses, defense lawyers have asked the court to, in the words of prosecutors, “engage in a fishing expedition” into Arbery’s mental health records to raise questions about his mental stability at the time of the shooting, including information from his toxicology report, to support the McMichaels’ contention that Arbery was “acting funny” and “not right.” (Prosecutors counter that the “only reason to put such evidence before the jury is to suggest that Mr. Arbery got what he deserved.”) This goes hand in hand with defense efforts to portray Arbery as having the kind of superhuman strength that always serves as a white alibi for murdering Black folks.

Defense attorney Bob Rubin, reusing a well-worn script, told CBS News that Travis McMichael is a “a good man who had to defend himself,” because he was “being attacked and overwhelmed by Ahmaud Arbery's strength” and had no choice but to “either fire that gun or lose his life at that point.” (Rubin told the outlet that a 17-year-old Travis McMichael saved a young Black man from drowning in a pool. Defense attorney Frank Hogue has an almost identical story about Greg McMichael rescuing a young Black sailor who was drowning.) In a motion filed in June, the defense team writes that Arbery, when trying to grab the shotgun Travis McMichael was aiming at him, wasn’t trying to protect himself from his killers, but was attempting an “assault to kill or seriously injury McMichael.” To support the contention that the McMichaels were just good guys with guns faced with a “violent, aggressive, dangerous, confrontational” attacker, they’re asking Judge Walmsley to OK testimony that would indicate “Mr. Arbery has a reputation” for being all of those things, which they claim offers insights into Arbery’s “intent and motive.”

I asked Earl Ward, a prominent New York City defense attorney and trial lawyer, about some of the defense’s filings, including the aforementioned motion to introduce Arbery’s “reputation.” The motions to prevent prosecutors from using the term “victim” or its photo request is typical for criminal defenders, he says.

“Let me start by saying Mr. Arbery was a victim. There's no doubt about that. But in a court of law, the argument is, there’s not a victim until the jury has determined there’s a victim,” Ward told me. “And if the government refers to him as the victim, it sends a message that the defendants on trial are the victimizers. It takes away the presumption of innocence, which is so key to our constitutional system. The same is true with bringing in a lot of photographs with family, which would go too far, in the sense that it appeals to sympathy. The government has to prove the case and sympathy shouldn't come into play. It’s consistent with the idea that there’s a presumption of innocence. Which is why most defense attorneys typically try to keep that out.”

But what about the effort to introduce what’s known as 404(b) evidence—testimony that Arbery was “aggressive” in the past? Ward told me that qualifies as “bullshit.”

“Typically, you cannot bring in evidence of the decedent’s behavior, unless the defendants knew about it. If they didn't know that Ahmaud Arbery had done something in the past, it can’t be used to justify their behavior in that moment,” Ward told me. “To just bring it in sort of randomly, because you want to prejudice the jury because they’re going to hear that he’s done some bad things in the past—what’s the relevance?”

Even as they lobby the court to put Arbery on trial, using every legal trick in the book to turn the victim into a predator, they want to stop the state from using any testimony about the fact that “the McMichaels were in possession of firearms at the time of their arrest,” that they “had other firearms in their home,” or that they “shoot their firearms while on the river.” They have also asked that racist texts and social media posts sent by the McMichaels and Bryan, which reportedly included frequent use of the n— word and jokes about shooting Black people, not be allowed as evidence.

The defense’s recent motions are tied to a strategy, as they expressly noted in their filing, to “rely heavily upon Georgia’s then-applicable citizen’s arrest statute.” The McMichaels contend they believed Arbery was responsible for a number of burglaries that had recently occurred in their neighborhood. Their lawyers will argue that, because of that “probable cause” belief, Arbery’s decision not to obey the white men stalking him was illegal, because it is “unlawful to resist lawful citizen’s arrest.”

Georgia’s racist, slavery-era citizen’s arrest law was repealed in May, primarily because of Arbery’s killing, with even rightwing Georgia Governor Brian Kemp writing in an op-ed that “Arbery was the victim of a vigilante-style of violence that has no place in our state, and some tried to justify the actions of his killers by claiming they had the protection of an antiquated law that is ripe for abuse.” Prosecutors have filed a motion to prevent the defense from arguing that the law was repealed because it “gave the Defendants the right to chase Mr. Arbery through the Satilla Shores neighborhood after not having seen him do anything and shoot him dead when he did not stop.”

The state has filed paperwork to push back against many of the defense’s motions. In one lengthy response, they offer a rebuttal to a specific request that also seems like a refutation of the defense’s entire scheme to blame Arbery for his own death.

“Had the defendants stayed at their homes and simply called 911, Mr. Arbery would be alive,” the document reads. “Instead, the defendants took it upon themselves to gather their firearms, get into their pickup trucks, and chase after Mr. Arbery...They chased him, attempted to hit him with the pickup trucks, assaulted him and repeatedly tried to falsely imprison him.”

“They were the initial aggressors, they stated the chain of events that led to Mr. Arbery’s death, and Mr. Arbery did nothing to initiate or instigate interaction with the defendants. For over five minutes, Mr. Arbery ran away from the strange, shotgun-wielding men, who were chasing him, and trying to hit him with pickup trucks. How terrifying it must have been for him to be hunted down in such a fashion.”

Jury selection in the case begins on Oct. 18. Lawyers for the McMichaels had petitioned the court to prohibit media from observing the process, but withdrew that motion after significant pushback. Bryan and the McMichaels also face hate crimes charges in a federal court.