When going to traffic court, the costs of wrangling an attorney to help plead your case can often exceed the ticket fine itself. And that’s assuming you can find a lawyer to take on such a low-stakes case. So why not skip legal fees altogether, and take counsel from artificial intelligence?

That’s a solution Joshua Browder, CEO of consumer-liberation startup DoNotPay, is testing out next month, when his company will pay two defendants going to traffic court up to $1,000 each to wear smart glasses that will double up as their attorneys.

Yes, we’re living in a simulation, and it involves sentient eyewear.

Well, sort of. The glasses will record the proceedings and a chatbot—built on OpenAI’s GPT-3, famous for transcribing ballads and high school essays on demand—will offer legal arguments in real-time, which the defendants have pledged to repeat, Browder told The Daily Beast. The locations of the hearings have been kept secret, to prevent judges from derailing the stunts ahead of time. Each defendant will have the option to opt out if they choose.

“My goal is that the ordinary, average consumer never has to hire a lawyer again,” said Browder.

DoNotPay, founded by Browder in 2015 while he attended Stanford University, states on its website that its mission is to help consumers “fight against large corporations and solve their problems like beating parking tickets, appealing bank fees, and suing robocallers.” Its app is supposed to help users navigate modern-day bureaucracy that interferes with doing everything from canceling subscriptions, to disputing fines, to bringing up litigation against anyone they may wish to sue. The company started out by helping users contest $100 parking tickets, but thanks to advances in AI, said Browder, they’re now helping clients fight bigger claims, like $10,000 medical bills.

The company’s latest trial will make use of CatXQ’s Smart Glasses. With square lenses and a spindly black frame, the glasses seem relatively unassuming, but they can connect to devices via Bluetooth and deliver sounds straight to the wearer’s cochlea (the hearing organ in the inner ear) through bone conduction (similar to how some hearing aids work). The chatbot will exist on the defendant’s phone as a regular app, absorbing audio through the device’s microphone, and dictating legal arguments through the glasses.

The chatbot glasses won’t be a marketable product anytime soon due to legal restrictions. In the U.S., you need a license to practice law, which includes both representing parties in court as well providing official legal advice. Plus, many states prohibit recording in courtrooms.

Nonetheless, Browder sees his company’s new experiment as an opportunity to reconceptualize how legal services could be democratized with AI.

But putting one’s rights into the hands of an algorithm as a solution to insufficient or inequitable legal representation is ethically worrisome, legal experts warned. The use of AI in the courtroom could create separate legal consequences for the defendants that are far more complex than a traffic ticket. Chatbots may not be the means-for-justice that Browder and others are envisioning.

With Prejudice

GPT-3 is good at holding a conversation and spitting out some interesting ideas, but Browder admits it’s still bad at knowing the law. “It’s a great high school student, but we need to send it to law school,” he said.

Like any AI, GPT-3 needs to be trained properly. DoNotPay’s law school for bots looks like mock trials run by team members at the company’s Silicon Valley headquarters in Palo Alto. The algorithms are nourished on datasets of legal documents from publicly available court records and DoNotPay’s own roster of 2.75 million cases, according to Browder, dating back to its conception in 2015. The bot going before a judge has been trained on recent traffic ticket cases taken from the same jurisdiction as the hearing, and a few adjacent countries in the state. A quarter of these cases are from DoNotPay’s own database, while the rest are from publicly available records.

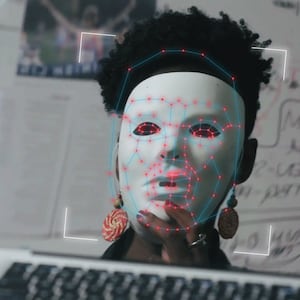

But all AI carries the risk of bias because society’s prejudices will find their way into these datasets. If the cases used to train an AI search engine are skewed toward finding people of color guilty, then the AI will begin to associate guilt with specific races, Nathalie Smuha, a legal scholar and philosopher at the KU Leuven in Belgium, told The Daily Beast.

“There is a risk that the systemic bias that already exists in the legal system will be exacerbated by relying on systems that reflect those biases,” she said. “So, you kind of have a loop, where it never gets better, because the system is already not perfect.” Similarly, not all legal cases are public, and the algorithm may only be trained on a subset restricted by specific dates or geography—which can distort the bot’s accuracy, Smuha added.

None of this is new to the American public, of course. Princeton researchers ran a study in 2017 to examine police officer discretion in speeding tickets in Florida, and found that a quarter of officers showed racial bias. The political scientist authors of the 2018 book Suspect Citizens ran an analysis of 20 million traffic stops in North Carolina spanning 14 years, finding that Black drivers were 95 percent more likely to be stopped.

Any AI trained on those datasets would be at risk of developing unfair biases against certain demographics—affecting how they may deliver legal advice in traffic court. Browder told The Daily Beast that DoNotPay has taken steps to limit any potential bias by ensuring that the part of the bot responsible for absorbing the substance of the case and making legal arguments does not know the identity of the client or any major personal details beyond vehicle type and traffic signage.

These bias concerns aren’t just for fighting traffic tickets. A justice system running on the automated legal utopia that Browder envisions, with more complex cases and an inability to hide client identities so easily, could exacerbate more severe systemic wrongs against marginalized groups.

In fact, we’re already seeing this unfold. Criminal risk assessment tools that use socioeconomic factors like education, employment, income and housing are already used by some judges to inform sentencing, and have been found to worsen disparities. The NYPD uses predictive policing algorithms to inform where they deploy facial recognition technology, what Amnesty International has called “digital stop-and-frisk.” In 2013, The Verge reported on how the Chicago Police Department used a predictive policing program to determine that Robert McDaniel was a “person of interest” in a shooting, despite having no record of violence. Last month, facial recognition algorithms led to the wrongful arrest of a man in Louisiana.

When asked about algorithmic biases, Browder said that people can use AI to fight AI—the bot puts algorithms into the hands of civilians. “So, rather than these companies using it to charge fees, or these governments using it to put people in jail, we want people to be able to fight back,” he said. “Power to the people.”

The lack of regulation around AI means this kind of outcome is far from certain.

A Can of Worms

Bias aside, defendants could also end up in hot water for the use of technology and recording—uncharted waters for the legal community. “Is [Browder] going to help erase their criminal conviction for contempt?” Jerome Greco, a public defender in the Legal Aid Society’s digital forensics unit, told The Daily Beast.

While DoNotPay has committed to paying any fines or court fees for clients that use its chatbot services, Browder does worry what could happen if the bot is rude to the judge—a misdemeanor could normally land a physical person in jail. And Smuha predicts that the chatbot’s malfunction wouldn’t be an adequate alibi: “A courtroom is where you defend yourself and take responsibility for your actions and words—not a place to test the latest innovation.”

And of course, there’s a risk that the algorithm could simply mess up and provide the wrong answers. If an attorney flubs your case through negligence, there are systems in place to make them liable, from filing complaints to suing. If the chatbot botches the legal arguments, the framework to protect you is unclear. Who is to blame: you? The scientists who trained the bot? The biases in the training datasets?

The technology is imperfect, said Smuha, because the software analyzes data without understanding what it means. “Take the sentence ‘that man is not guilty,’” she said. “The software has no idea what ‘man’ is or what the concept of ‘guilty’ is.” That’s in stark contrast to the years of training and ethical standards that lawyers are held accountable to. “There will be a risk that the system will speak nonsense.”

As a result, AI-enabled databases and pattern-spotting tools simply speed up the legal process, as opposed to determining a case’s outcome, “because the tech is just not accurate enough yet,” Smuha said.

Browder seems undeterred, and is responding to such criticisms brashly. Last week, he trolled the law community on Twitter by promising $1 million to any person or attorney with an upcoming Supreme Court case to follow the chatbot’s counsel. “I got so much hate from all the lawyers,” he said. The next day, he tweeted he would raise this reward to $5 million, later deleting the post.

Greco finds the whole spectacle unsettling, and takes issue with DoNotPay finding willing participants to test its experimental AI via poorer clients who can’t afford a physical attorney. “Using them as guinea pigs to test an algorithm? I have a real problem with that,” he said. “And I think it overlooks the other solution… Why don’t we put more money into people having proper representation?”

But Browder thinks this is just the beginning for consumer rights. “Courts should allow it, because if people can’t afford lawyers, at least they can have some help.”