On a clear, humid day in August 1969, a photographer climbed up a stepladder in the middle of a north London street and adjusted his Hasselblad.

Then, as a policeman directed confused traffic, four men stepped onto the zebra crossing and began to march, back and forth.

“Come on, hurry up now, keep in step,” John Lennon barked.

He was bored and distracted; he wanted to be inside the studio finishing the album, “not posing for Beatles pictures.”

Eventually, Paul McCartney, wilting in the summer heat, kicked off his shoes and went barefoot.

The photographer snapped another frame. For decades afterwards, obsessive fans would focus in on details like this: What did the barefootedness mean?

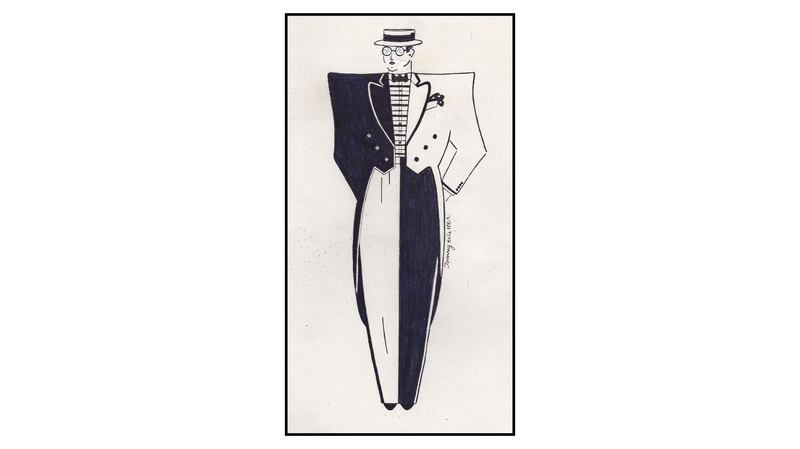

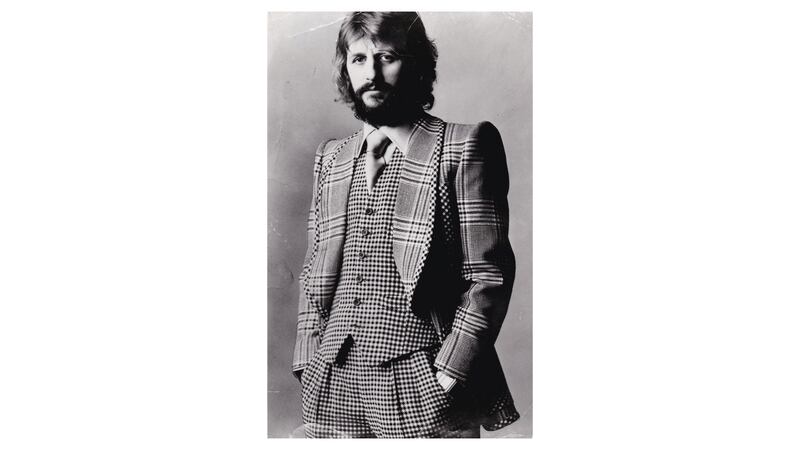

And the Volkswagen Beetle in the background, what about that? Indeed, fans would analyze and read symbolism into absolutely everything in the picture except, it seems, what the Beatles were wearing. George Harrison chose denim. But the other three matched in immaculate bespoke, all designed by a young British tailor named Tommy Nutter.

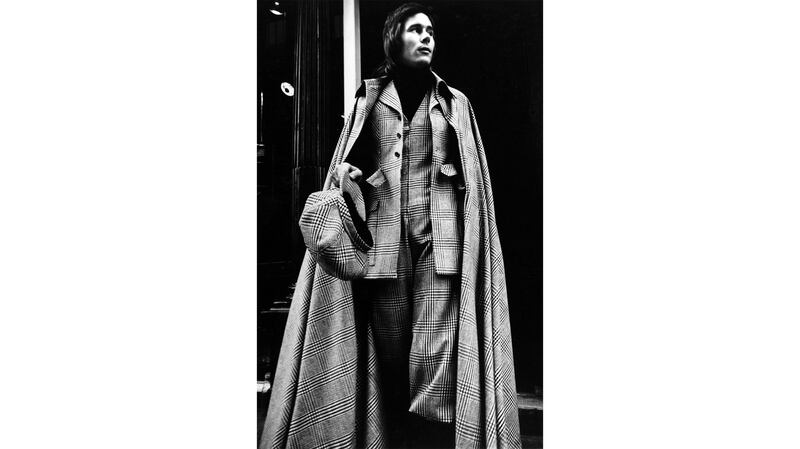

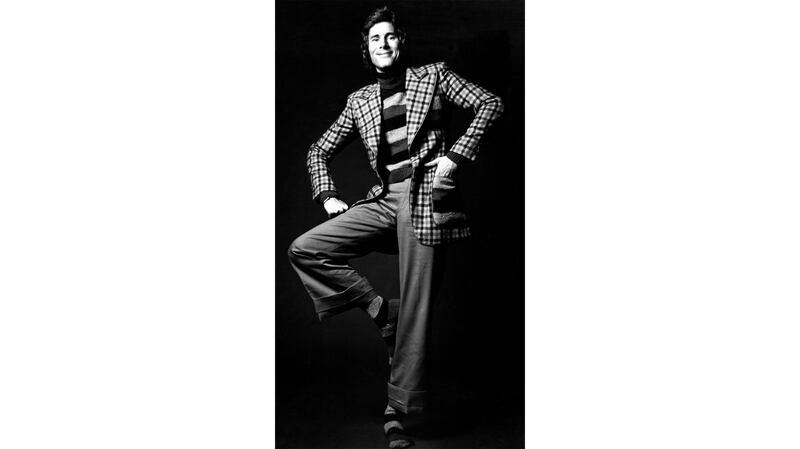

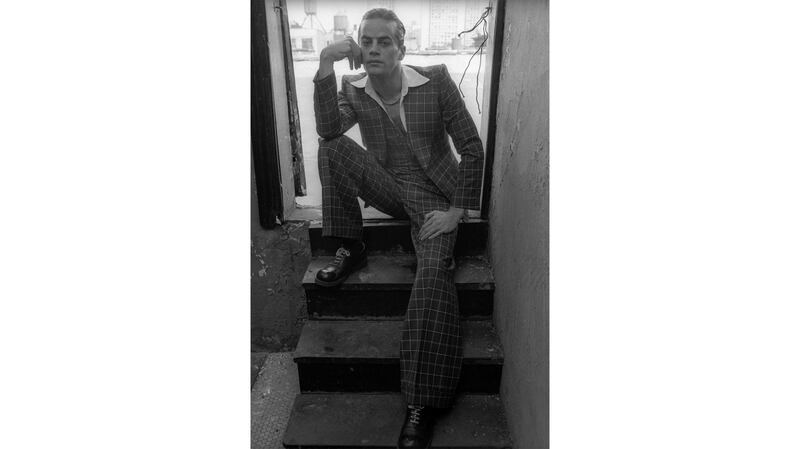

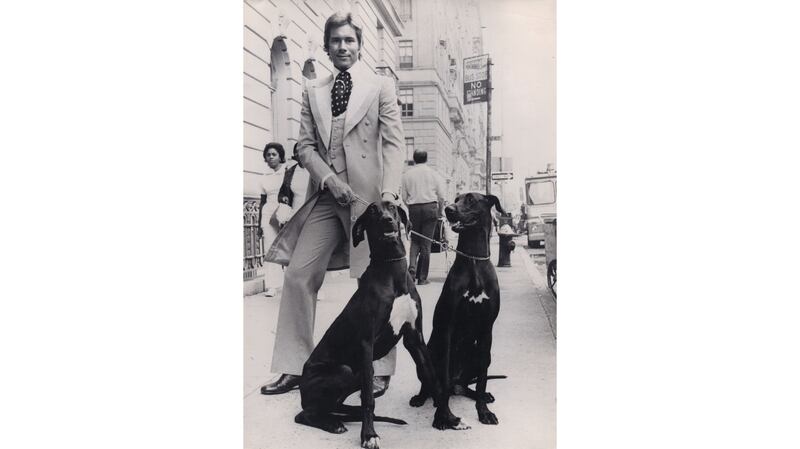

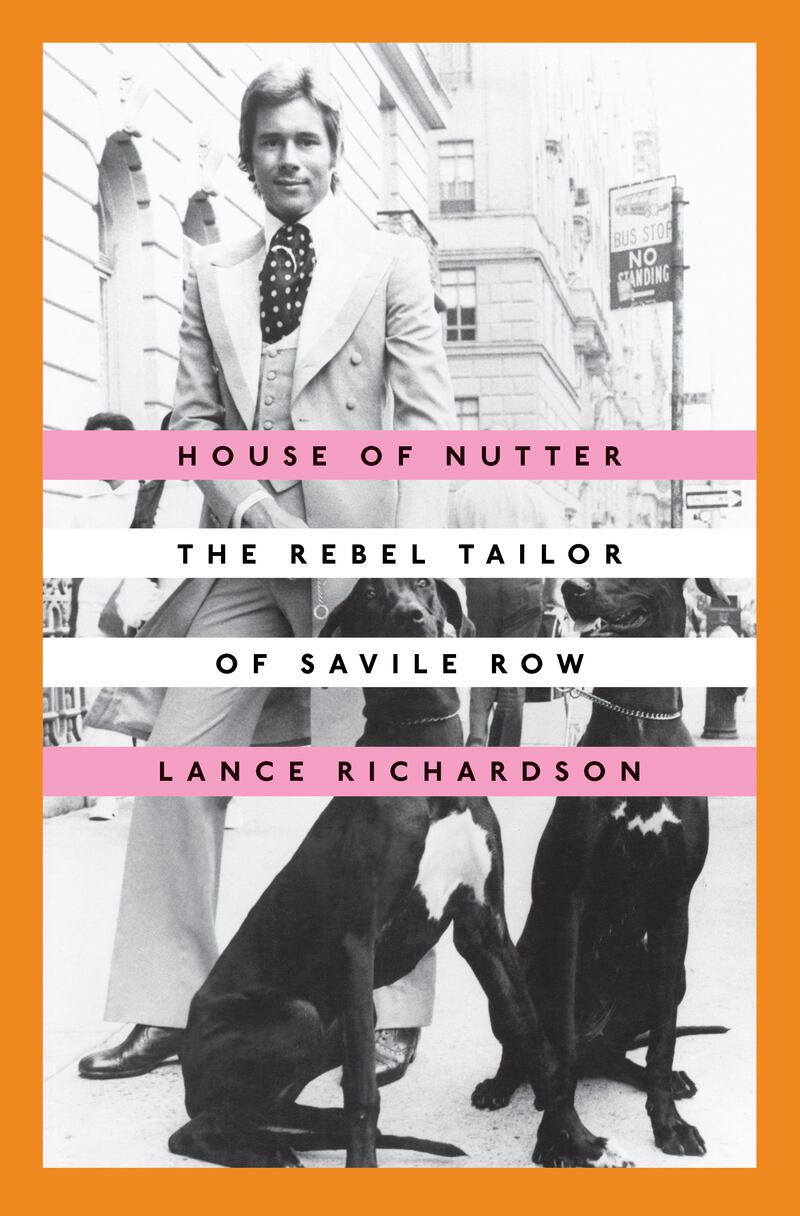

At the time Iain Macmillan took the photograph that would become one of the most famous ever—the album cover of Abbey Road—Tommy Nutter was a superstar in his own right.

According to the Daily Mail, he was “in the class of actor Terence Stamp, photographer Brian Duffy, and hairdresser Vidal Sassoon, all the stylish young Londoners who have shot themselves out of their backgrounds and into the new aristocracy.”

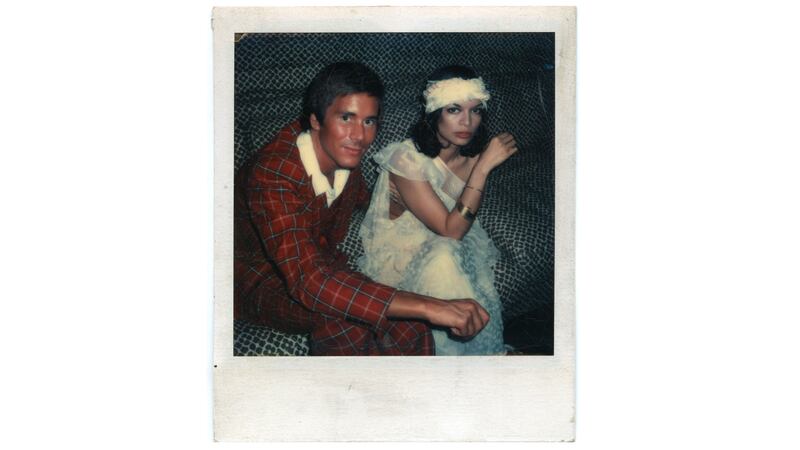

His boutique on Savile Row was “the place for men’s clothes… a whizz-bang success.” He had dressed Lennon at his infamous wedding to Yoko Ono, and he would go on to dress Mick Jagger at his equally infamous one to Bianca Pérez-Mora Macias.

Then he would dress Bianca herself, in attention-grabbing men’s suits during the height of the women’s liberation movement. “Mick didn’t like that at all,” Bianca Jagger later recalled. “He said that a man’s tailor was very special. It was a personal thing that a woman shouldn’t intrude on. But I went anyway.”

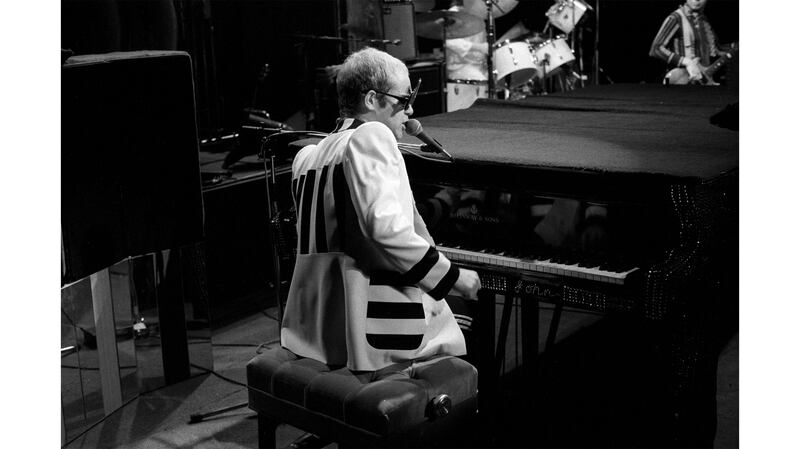

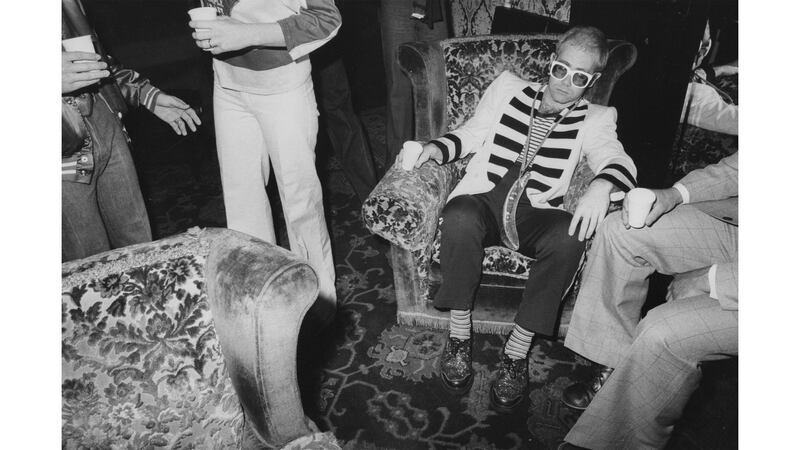

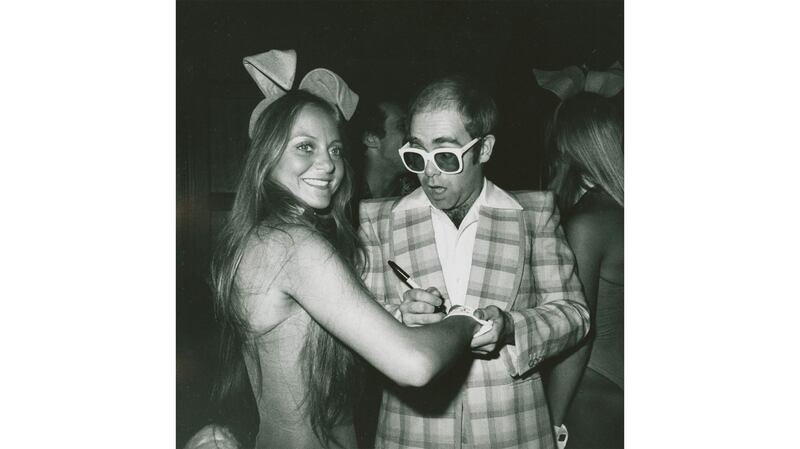

Over a three-decade career, Tommy Nutter would dress everything from Diana Ross to Elton John, David Hockney to Jack Nicholson (as the Joker, in Tim Burton’s Batman). And yet, despite all this success, most people today have never even heard of him.

Having spent the last two years excavating Nutter’s dramatic biography, I have often asked myself why this is. How is it possible that the man behind some of the most iconic looks of the 1960s and ’70s draws, at most, vague recognition when I mention his name?

Partly it is a question of marketing. The better marketed your name, the more lasting it will be in the memory of consumers. Nutter did everything Giorgio Armani did, for example, except get his suits on Richard Gere in American Gigolo and his face on the cover of Time (“Just the name… the name alone… the very mention of the name sends off sparks and sets up a clamor like a French fire drill,” the magazine hyperventilated in 1982).

But I have also come to suspect that the oversight is related to HIV/AIDS, which Nutter contracted sometime in the late-1980s.

In some ways we have never been more attentive to what was lost during the AIDS crisis.

In the past few years, memoirs by Cleve Jones and Fred Hersch have detailed what it was like to live through the horror, and How to Survive a Plague, a history of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) by David France, has documented the grassroots resistance in detail. Randy Shilts' And The Band Played On, Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, and Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart remain totems of that era in their own right.

When recalling the dead, most popular narratives also have a tendency to recycle a specific list of names, like Freddie Mercury, David Wojnarowicz, Robert Mapplethorpe.

These handful of artists are important, of course, but they are not the sum total of the toll, and repeatedly evoking them as a shorthand for describing what the plague cost the culture can also work to obfuscate the contribution of others. To use an analogy: It is like focusing on the death of a few lead actors while ignoring that the supporting actors also died, along with most of the chorus.

Writing the story of Tommy Nutter reminded me that there are many creative figures who have slipped through the fault-lines in our attempts at a reckoning: people who, while not as famous as Derek Jarman or Rock Hudson or Peter Hujar, nevertheless made beautiful things and generated worthy ideas, or (if they passed when they were particularly young) promised to grow up and offer something great.

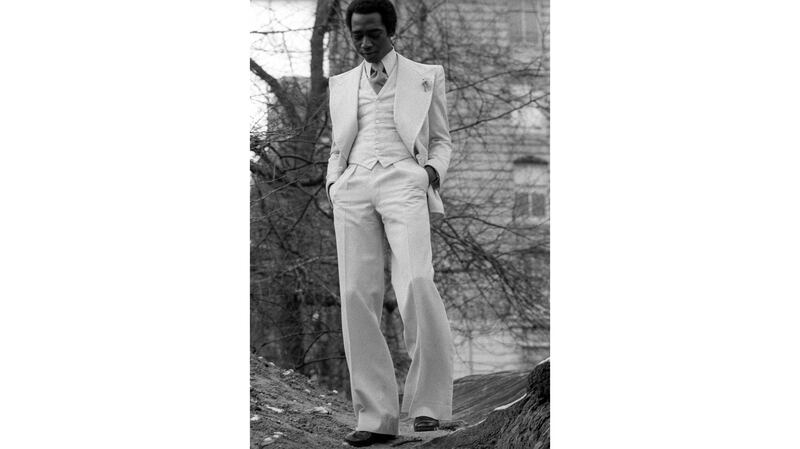

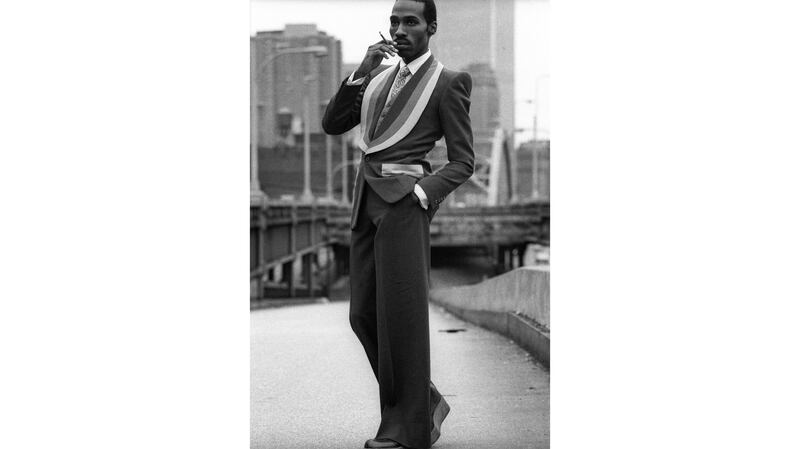

In the fashion world, for example, Willi Smith was a black designer from Philadelphia who was running a small empire when he died of “pneumonia, complicated by shigella”—a euphemism in The New York Times—at the age of 39. Patrick Kelly was the first American (also black, from Mississippi) to be welcomed into the French Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter when he died at 35.

My idea of AIDS was underestimating its circle of devastation. Halston and Perry Ellis may have been killed by AIDS-related ailments, but so were innumerable others who, in time, might have superseded them in terms of fame and accomplishment.

Those people are worth remembering too, which is why the AIDS Memorial on Instagram is so remarkable: It attempts to mix, without distinction, that well-rehearsed list in with thousands of other lesser-known names, including John Bernd, Sandra Bréa, Michael Grumley—and Tommy Nutter.

Nutter found out he had HIV/AIDS and responded with characteristic humor. When he told a friend about his diagnosis, she encouraged him to be positive.

“I just said that,” he replied. “I am ‘positive.’”

But his decline, like the decline of too many others, was wretched and excruciating, accompanied by tremendous weight loss (until even a sheet became too heavy), opportunistic infections, and the brutal onset of dementia. Always something of a vain man, he withdrew from public view, but the media was relentless and splashed his condition across the newsstands anyway: “Tailor to the Stars Dying of AIDS: Tommy Nutter Has ‘Days Left’.” In the end, he died of “Bronchopneumonia,” with his mother sitting sentinel by his bedside. It was Aug. 17, 1992; he was 49 years old.

As I wrote my book, I was very conscious that what I was doing was an act of restitution, an attempt to complete the record, set it straight, give the man his due. But tracing out the contours of this person’s life story turned out to be a more sobering experience than I had initially expected, illuminating my ignorance of what had happened just a little more than two decades ago.

Nutter has been credited as an enduring influence by Tom Ford and Tommy Hilfiger.

This February, Todd Snyder debuted a collection at New York Fashion Week that even paid homage to Nutter’s designs. That is all great; but what, I have found myself wondering, would Nutter had done himself if he’d lived just four more years to receive the life-saving cocktail? Perhaps he would be sending his own clothes down the runway instead, his name conjuring associations with the titans of 20th century music and art.

I have also found myself wondering: who else? Who are we still overlooking in our selective remembrance of the past? Because if Nutter, for all his achievements, has fallen into obscurity, then thousands of others—hundreds of thousands—with less fame but with lives of creativity and innovation, have also been forgotten.

How radically different culture, popular and otherwise, might look today if they were all still around to share their imaginations with the rest of us.

Lance Richardson is the author of House of Nutter: The Rebel Tailor of Savile Row, published by Crown.