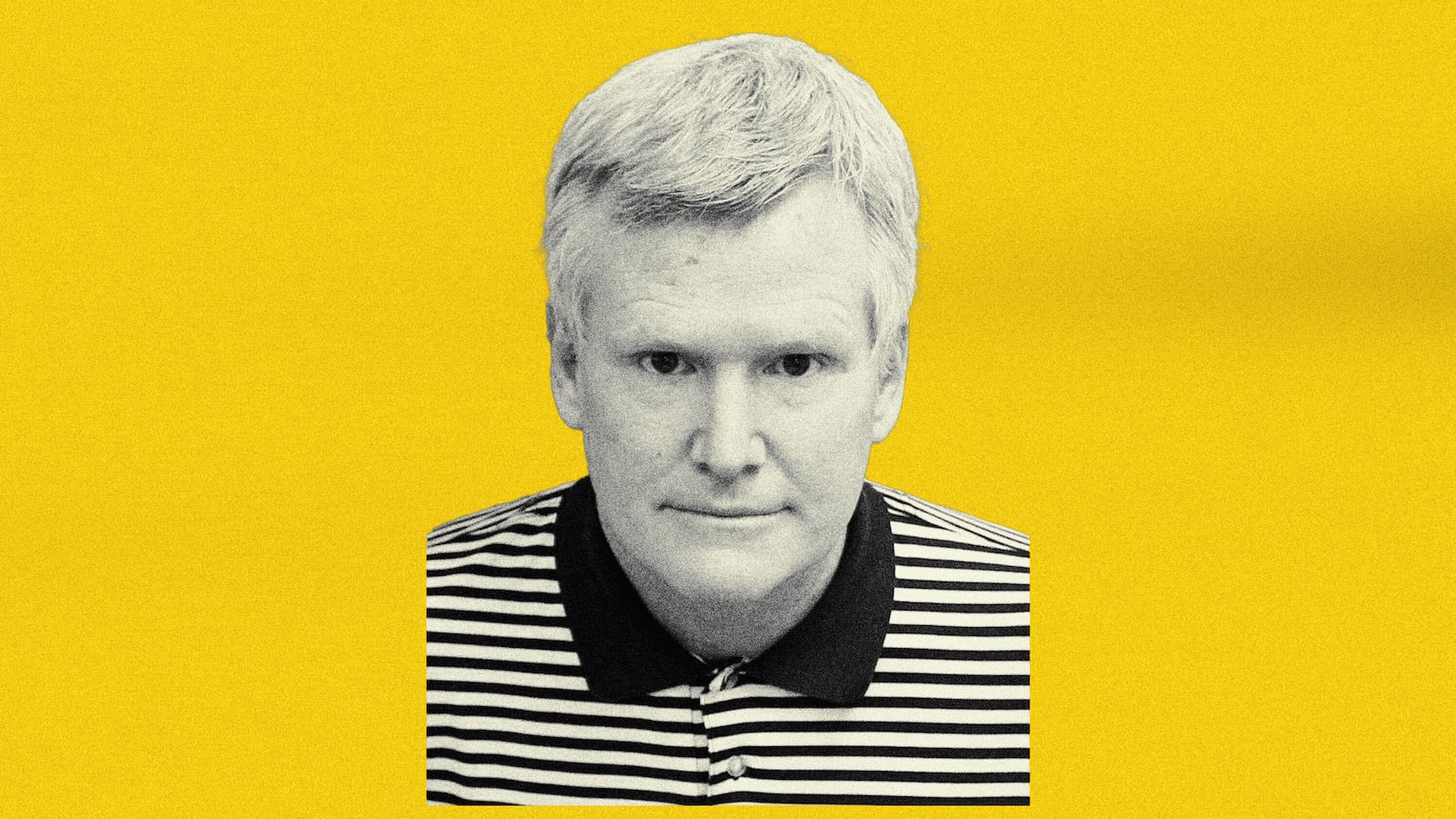

Hours before Alex Murdaugh allegedly killed his wife and son near the dog kennels at their family estate, the former lawyer knew he was in trouble.

Jeanne Seckinger, the CFO of Murdaugh’s family law firm, had already confronted him a month prior about improperly depositing money from a civil case settlement and got him to allegedly admit he was trying to secretly move money into his wife’s name. But Seckinger told Colleton County jurors on Tuesday that she approached Murdaugh on June 7, 2021, about a different, and more serious, monetary question: What happened to $792,000 in legal fees owed to the firm that had gone missing in a case Murdaugh handled?

“He looked at me with a pretty dirty look, one I had not seen before, and said, ‘What do you need now?’” Seckinger testified about a conversation that began outside his office. “My concern was that he had stolen fees and they were paid to him personally.”

But as Murdaugh was scrambling to explain the missing funds, Seckinger said the conversation was cut short when he got a phone call that his father’s condition was “terminal” and he was in the hospital. She said that she didn’t push him about the missing funds after the call and assumed that he left the office to spend the evening with Randolph Murdaugh III. (Murdaugh III, who had once worked at the same firm, died three days later.)

Instead, prosecutors allege, Murdaugh went to his family’s hunting estate, where he fatally shot his 52-year-old wife, Maggie, and his 22-year-old son, Paul, in a twisted attempt to shield the discovery that he had been bilking funds from his law firm and clients for years.

Murdaugh, 54, has pleaded not guilty to two counts of murder and two counts of possession of a weapon during the commission of a violent crime. Prosecutors claim he blasted his wife and son with two different guns before taking steps to cover up the double homicide. Defense attorneys, however, insist that there is no concrete evidence tying Murdaugh to the grisly murders and insist that their client had no motivation to murder his “wonderful family.” If convicted, he faces up to 30 years in jail.

Over the last two weeks, prosecutors have called over a dozen witnesses to the stand to describe how Murdaugh’s wife and son were murdered. So far, the main piece of evidence to prove their argument is a video Paul Murdaugh recorded in the dog kennels minutes before his murder, in which prosecutors say Alex and Maggie can be heard in the background.

But Seckinger has been the first witness to provide insight into Murdaugh’s mindset at the time of the murders—and bolster the prosecution’s argument that the slayings were motivated by a desire to hide his other crimes.

Seckinger, who said she knew Murdaugh in high school and is in charge of bookkeeping for the firm, described him as a mediocre lawyer who was only successful because he had “the gift of the gab.”

“He was successful not from his work ethic, but his ability to establish relationships and to manipulate people into settlements and clients into liking him,” she said. “The art of bullshit, basically.”

That gift, she said, was one reason he was able to talk his way out of trouble in May 2021 when she uncovered a disbursement sheet for Murdaugh’s recently won case that showed his fees were going to an unknown company. During the confrontation, Murdaugh denied any wrongdoing but later admitted that he was trying to move his money into Maggie’s name—a fact that led Seckinger to believe he was trying to hide his assets amid a pending civil case. (At the time of the murders, Paul was facing charges in connection with a fatal 2019 boat crash and Murdaugh had been named in a civil suit in connection to the incident.)

“That is hiding assets,” she said. “We are not going to be part of any hiding of assets or any wrongdoing. We were very concerned that he was trying to do that, and we didn’t want to be a part of it.”

Seckinger confronted Murdaugh again the day of the murders after a paralegal flagged that funds were also missing in another one of his cases.

Under cross-examination, Seckinger clarified that she was not accusing Murdaugh of stealing money during the June 7 conversation—but was instead worried that he was trying to hide the funds from disclosure and was asking where the funds were located.

She said she pushed Murdaugh to “prove” that he did not take the money, prompting him to assure her that the money was probably in an account of the other lawyer who had worked on the case and that he needed “time” to retrieve it.

The conversation, however, ended after Murdaugh received the distressing call about his father. Sometime later, Seckinger testified, she was surprised to see Murdaugh still in the office around 4 p.m. when he asked her for information about his 401k form and said he was working on his financial records for a hearing about the boat crash that was scheduled for later that week.

Prosecutors say that about four hours after the conversation, around 8:50 p.m., Murdaugh killed his wife and son.

Seckinger said she learned about the murders around 10:30 p.m., soon after Murdaugh had called 911 to report the crime. She said that the firm rushed to Murdaugh’s side, and avoided asking further questions about his finances because they were worried about his “sanity” and knew he had been taking “pills.” (Murdaugh has previously admitted to a two-decade addiction to opioids.)

“We were concerned about Alex,” she said.

The concern vanished, however, in September 2021 when Seckinger said she learned that Murdaugh “stole the money [and] that he’d been lying” about the legal case she confronted him about the day of the murders. She said she had the “sickest feeling” as the company began to look into Murdaugh’s finances and realized that he had set up a fake company account to funnel settlements from clients for years.

The firm forced him to resign the next day after Murdaugh confessed to stealing the money. The day after, Murdaugh called 911 to report he had been shot in the head on a back road in the Lowcountry.

He has since admitted to orchestrating the Sept. 4 attack in a botched assisted suicide scheme so his only surviving son, Buster, could receive his $10 million insurance payout.

On Tuesday, after going through dozens of checks and other financial records that showcased the breadth of Murdaugh’s financial schemes, prosecutor Creighton Waters asked Seckinger if she “really” knew the man she worked with for decades.

“I don’t think I ever really knew him,” Seckinger answered. “I don’t think anybody knows him.”