Richard Hamilton, the title of the latest show to take over London’s Tate Modern, may be short and sweet, but the exhibition is extensive. Never before has a retrospective of the father of British pop art explored so intricately every twist and turn of the artist’s life and complex mind.

Hamilton was more than an artist: as the exquisite catalogue accompanying the exhibition explains, he was a “painter, teacher, exhibition organizer, political activist, graphic artist, typography designer, media-experimentalist and champion.” With a long career that started in the late 1940s and ended with his death in 2011, he was known for taking the existing art styles and subjects of the day, and approaching them in exciting and transformative ways. He wholeheartedly abandoned the notion of an oeuvre unified by style, form, and technique: he liked to investigate, deconstruct, and reinvent things. His creations come in an extraordinary range of mediums and look to genres inspired by popular culture, science, and art history. Hamilton believed that you could only understand something by making it. And, for the most part, he did understand—the sheer variety of his works famously once led him to ask, “What the hell is going on here?”

His story begins across the river Thames and along London’s Embankment. To coincide with the Tate’s retrospective, the Institute of Contemporary Arts is hosting two of Hamilton’s 1950s installations, on display until April 6. Man, Machine and Motion (1955) and an Exhibit (1957) were presented at the Institute’s original location on Dover Street almost six decades ago. Recreated today, the installations demonstrate the aesthetic and conceptual concerns of the artist as exhibition-maker, along with his methodological approach—Hamilton designed them to be flexible, with movable frames that encouraged different perspectives and points of view. They also attest to a constant in his eclectic artistic career: his long-standing relationship and work with the ICA.

Just a hop (over the river) and a skip (this time, along London’s Southbank) away, visitors arrive back at the Tate, where the majority of the exhibition is taking place. The objects on show here represent the span of Hamilton’s career: from stylized toasters to angel-decked interiors, fashion-world faces to the ‘dirty protest’ of the IRA inmates, there’s no limit to the works on display.

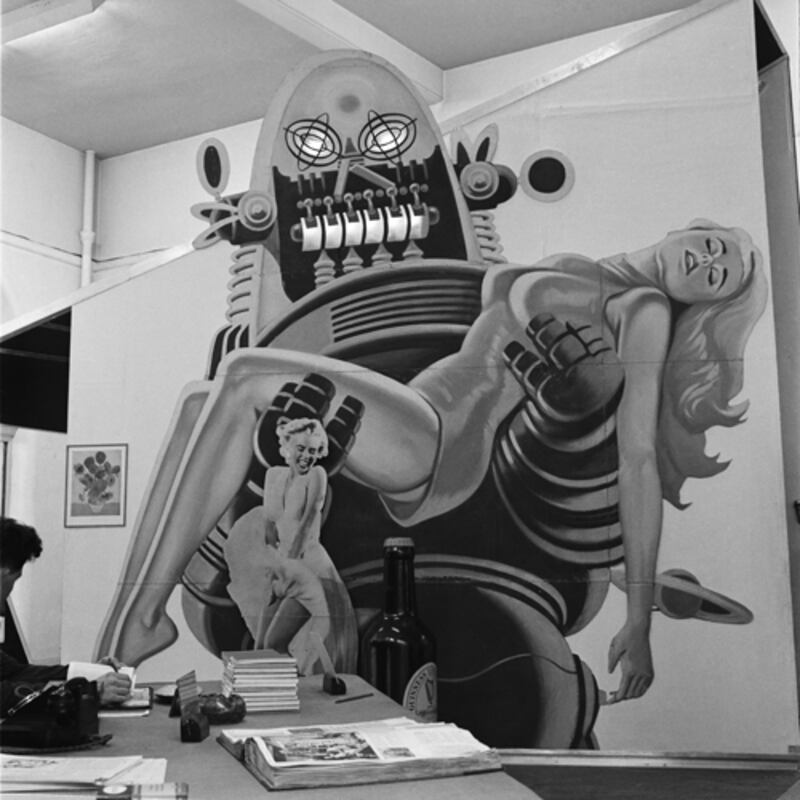

Upon entry to the exhibit, visitors are introduced to Hamilton through an early self-portrait, an etching and aquatint on paper the artist made in 1951. Soon they’re standing in front of one of his most well-known installations: Fun House (originally built in 1956, and reconstructed in 1987). In 1956, architect and critic Theo Crosby organized an exhibition called This is Tomorrow at the Whitechapel Gallery in London’s edgy East End. Hamilton partnered with architect John Voelcker and artist John McHale, and together they contributed Fun House. The immersive structure is the centerpiece of the Tate’s carefully curated show, and it justifies its position by touting a vast collection of Hamilton’s other works on its walls. The chosen images might be described as being more kitsch than chic—a plate of spaghetti and meatballs, matchsticks poking out of a bottle of pineapple distilled vinegar (whatever that is), and an overflowing bowl of baked beans, are among others that make the grade. The jukebox plays a medley of sixties tunes, an apt and agreeable feature.

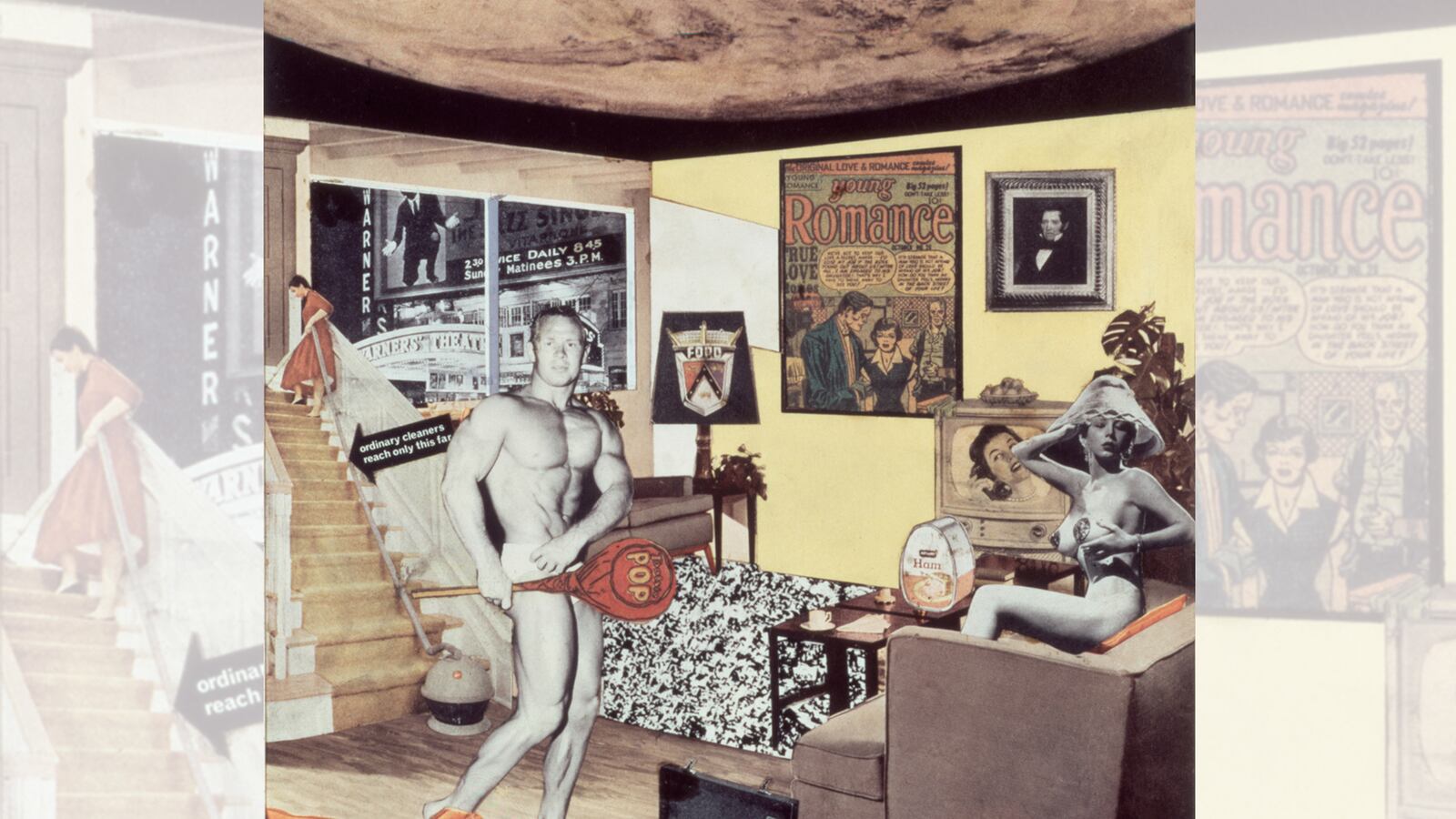

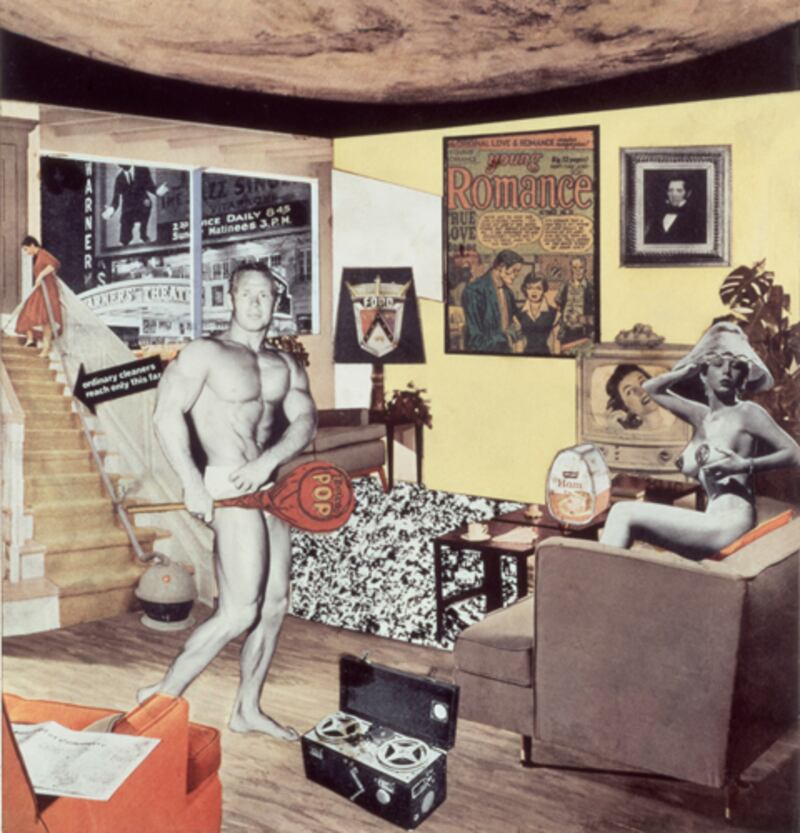

A collage Hamilton created for This is Tomorrow’s catalogue hangs opposite the Fun House. It’s called, Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? (1956). Is it the modern Adam, a muscled man mooching nonchalantly around the suburban living room in nothing but his briefs, a big lollipop jutting from his loins? Or is it Eve, topless but topped with a lampshade? Or better yet, is it the super-efficient housemaid, complete with vacuum cleaner, who’s made it past the sign on the staircase that reads “ordinary cleaners reach only this far”?

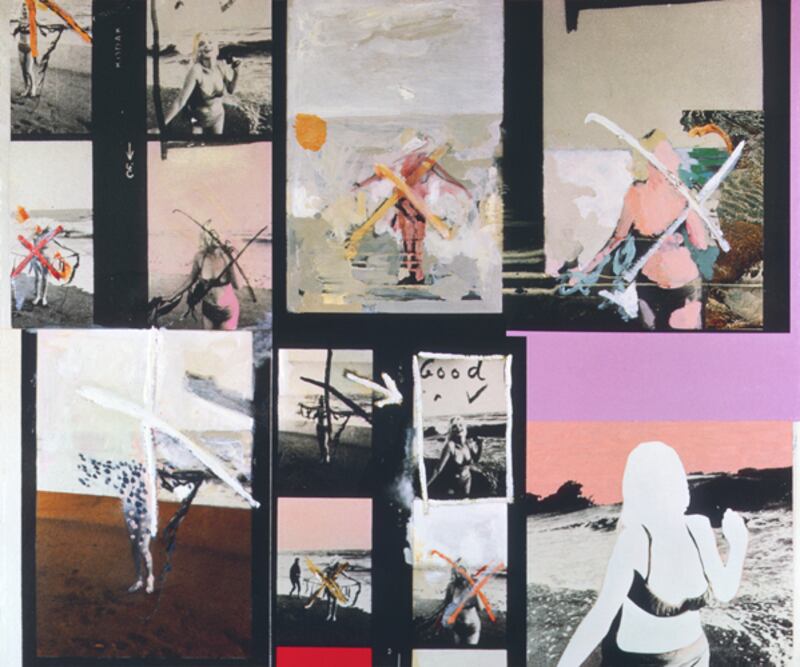

Hamilton explored characters from various walks of life in his paintings of the 1960s. One of the exhibit’s rooms, ‘People, 1964-67,’ presents works that range from close-up portraits of politicians and Hollywood stars to sweeping shots of anonymous crowds littering non-descript landscapes. For Bathers I (1966-7), Hamilton enlarged a photograph of people mingling on a long stretch of beach; as a result of the zoom, the figures have melted into indistinguishable ink-like blots.

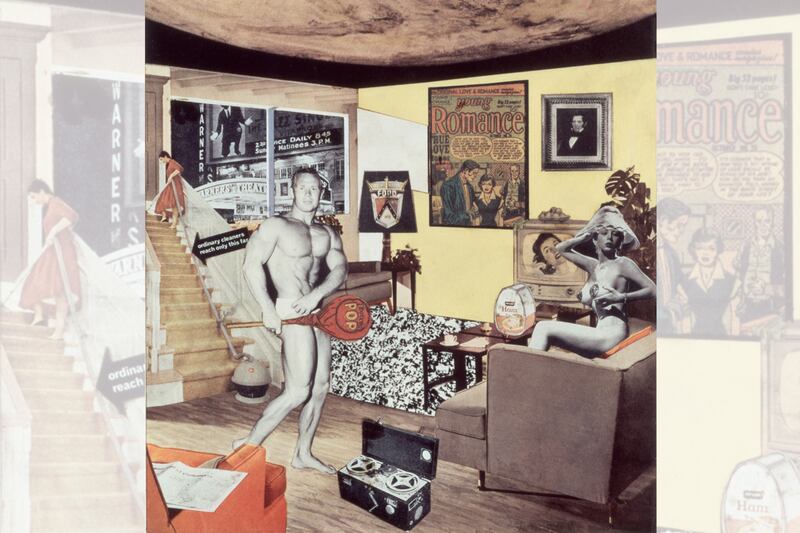

Though its subject is featureless in certain snaps, My Marilyn (1965) is evidence of Hamilton’s more personal human studies—and his avid engagement with popular culture. After Marilyn Monroe’s death, Hamilton saw a contact sheet of images of her taken by photographer George Barris. Marilyn had marked the sheet herself, and Hamilton took the editing process one step further, reproducing four of the images in My Marilyn, highlighting some with paint and erasing others. Marilyn features on the outside of Fun House too, a blown-up cutout from the famous subway grate scene, where she was captured in her billowing white dress.

Monroe wasn’t the only iconic figure to catch Hamilton’s ever-wandering eye. Another room is devoted to his love affair with Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp is partly responsible for the incessant eclecticism of Hamilton’s oeuvre—he too regarded each piece as a separate problem—and the younger artist’s devotion to his mentor’s teachings never wavered. Hamilton reconstructed Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915-23) in 1965-6. It is exhibited at the Tate along with the mass of preparatory material he used to create it.

Hamilton’s steadfast loyalty and attention to detail stretch far beyond a faithful depiction of human fingers and toes. The room ‘Design—Architecture—Products, 1964-79’ records his relationship with manufactured goods. Consumer products occupied a special place in Hamilton’s heart; whether or not they inhabited his home is trickier to tell. He began work on his Toaster studies in 1966, a series of prints combining photography and different printing techniques, and he continued to revisit the theme through 2008—though by this time he’d upgraded to Toaster deluxe. Still, people play a part in these works: visitors stand in front of the appliances and see their faces, infuriatingly blurred in the toasters’ reflective chrome.

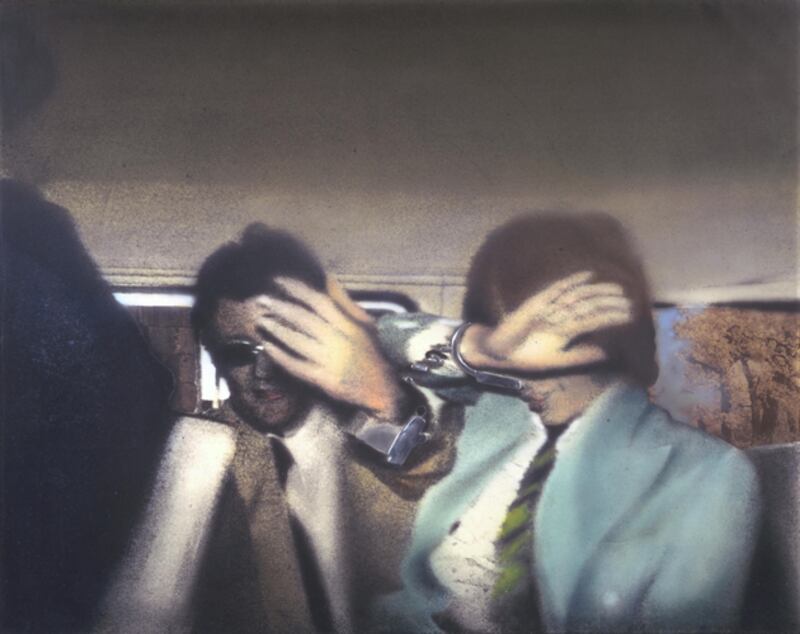

The idea of seeing and being seen continually pops up in Hamilton’s works, but not always to playful effect. Along with the glitz and the glamour of the era, Hamilton also recorded its troubling events. He was deeply interested in the media’s contortion of images; once again, he took the issue one step further, transforming the contorted images themselves. Swingeing London 67 (1968-9) is Hamilton’s response to the arrest of Mick Jagger and Robert Fraser (Hamilton’s art dealer) for possession of drugs in February 1967. He presents a series of paintings based on photographs of the pair’s arrest, cuffed hands raised as they attempt to shield their faces from the paparazzo’s prying lens. Hamilton’s title is a reference to the judge’s ‘swingeing sentence’ for Jagger and Fraser (three months and six months respectively). Clearly swinging London wasn’t always a happy-go-lucky place.

Treatment Room (1983-4) is one example of later installations that examined domestic culture and politics. The room stands in stark contrast to the chaotic and colorful Fun House; a plastic red bucket in one corner is the only thing to brighten up an otherwise sterile room. A television hangs above a hospital bed playing Margaret Thatcher’s 1983 Conservative Party Election Broadcast on a continuous loop. Hamilton subscribed to the Duchampian practice of not telling the viewer what to think, but the message here (surveillance and programming) comes through loud and clear.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Hamilton continued to tackle controversial subjects in his art. But his later works weren’t all doom and gloom. Once past Tate’s more newsy Hamilton rooms—dedicated to his documentation of the Gulf War, the war in Iraq, and of course The Troubles in Northern Ireland—visitors will find themselves re-immersed in a room of friendly and familiar folk. ‘Polaroids and Portraits’ is devoted to candid snapshots of an array of artists and Hamilton’s friends. A long wall is punctuated with famous faces: among others, Paul McCartney, Robert Rauschenberg, and George Segal look viewers in the eye as they walk past. Given pride of place, enlarged, and hung in relative isolation on the opposite wall are portraits of Hamilton’s close friends Dieter Roth and Derek Jarman.

The Tate brings the exhibition to a close with a room dedicated to Hamilton’s late work. He completed his last paintings, a series of three digital prints, just days before his death. Inspired by Balzac’s novella The Unknown Masterpiece, first published in 1831, these three pictures depict the artists Titian, Poussin, and Courbet standing over a reclining nude. In typical fashion, Hamilton is ever-present—the easel in the background is shaped in the form of a capital ‘H.’ He has also, as usual, tampered with the image; whereas Balzac’s protagonist, Frenhofer, failed to paint a perfect nude, Hamilton’s is computer-enhanced and hyper-realistic. A fabulous farewell.

Richard Hamilton will be on display at London’s Tate Modern from February 13 until May 26, 2014