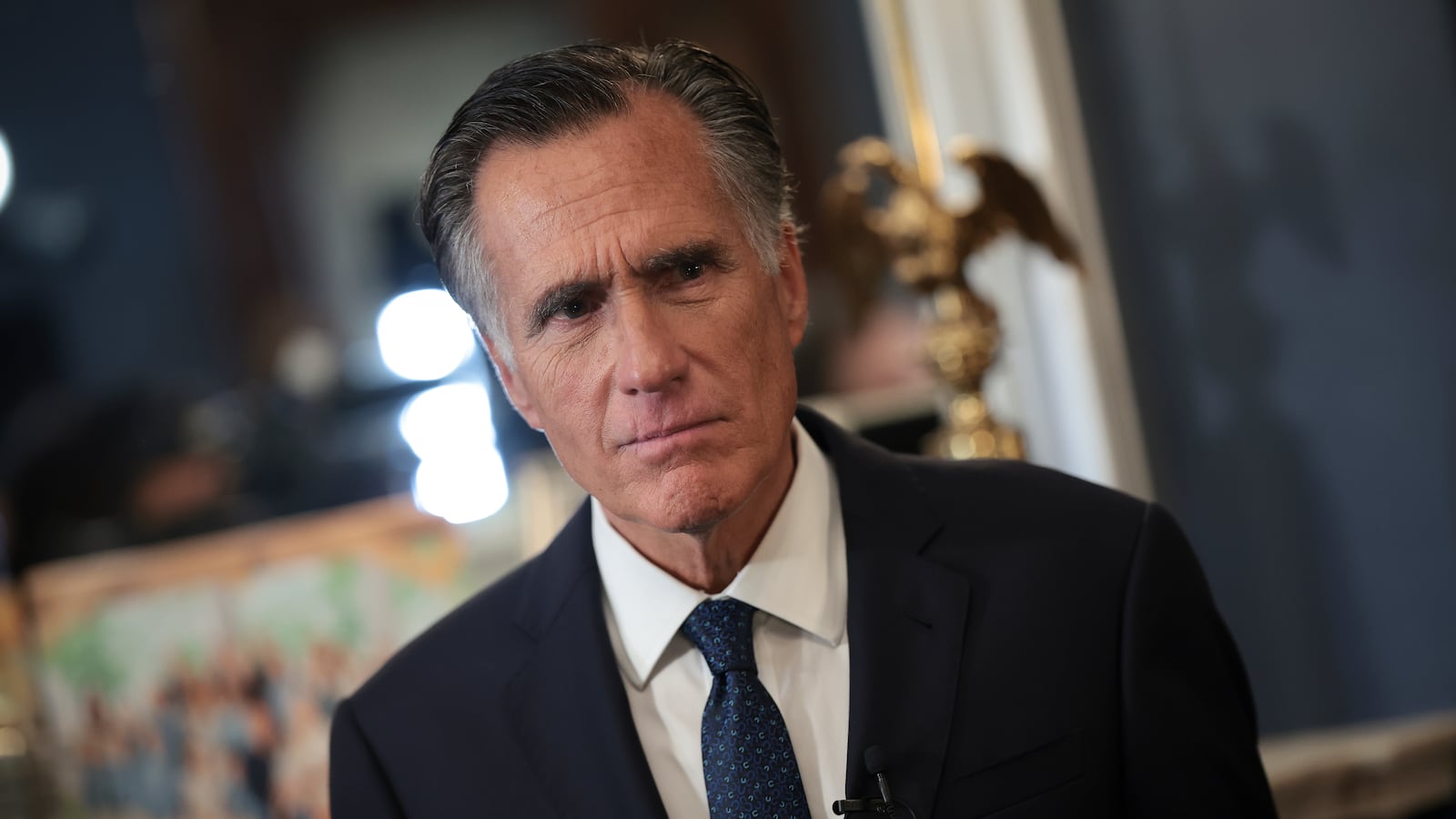

Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT) began telling his inner circle that he was weighing retirement earlier this year. On Wednesday, he told the rest of the world, saying he would not run for re-election and calling for both Joe Biden and Donald Trump to make way for a “new generation of leaders.”

Hours after Romney’s announcement, The Atlantic dropped a bombshell of its own: One of the magazine’s journalists, McKay Coppins, has been working with the Utah senator to chronicle his political life for the last two years. Romney gave Coppins superlative access to both his public and private life, turning over hundreds of pages’ worth of emails, texts, and personal journals. In one case, Romney literally took a crowbar to a locked filing cabinet to get at records for the reporter’s use.

The result is his forthcoming biography, Romney: A Reckoning, a portion of which was published in The Atlantic on Wednesday afternoon. The nearly 10,000-word extract reveals how Romney’s high hopes for his time in the Senate turned into disillusionment and eventual ostracizing from his own party.

It also paints a portrait of a deeply isolated, existentially drained lawmaker who watched with disgust as his colleagues groveled to Trump’s face while laughing behind his back—before Jan. 6, 2021 changed everything.

And, as it turns out, Romney is as good at brutally calling out two-faced legislators as he is at bearing witness. Here are all the most revelatory—and juiciest—tidbits from the excerpted story of a man who, in his own estimation, became “the turd in the punchbowl” of the Republican Party.

‘Almost without exception,’ Senate Republicans rolled their eyes at Trump ahead of the 2020 election

So many Republican senators privately expressed their support for Romney’s public criticism of Trump that the Utahn began keeping count, telling staffers he’d had more than a dozen nearly identical exchanges. He recalled one senior lawmaker complaining to him: “[Trump] has none of the qualities you would want in a president, and all of the qualities you wouldn’t.”

“Almost without exception,” Romney told Coppins, “they shared my view of the president.”

In March 2019, Trump descended on the GOP senators’ weekly caucus lunch to wax lyrical about his recent victories. The senators broke into “a standing ovation fit for a conquering hero,” Coppins writes, before settling in to listen politely as the then-president jabbered almost incoherently. The minute Trump left the room, according to Romney, the entire caucus burst into laughter.

That includes Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell

Some of Romney’s most withering observations in the extract are reserved for Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY), who served as Senate Majority Leader until 2021. The McConnell that Romney saw behind the scenes was very different from the one who played Trump’s toady in public. In private conversations, McConnell called Trump an “idiot” and told Romney he was “lucky” for being able “say the things that we all think” about him. (A McConnell spokesperson disputed this.)

McConnell’s alleged distaste for Trump came out in full force during the first impeachment trial. After the trial’s impeachment managers had finished their presentation, Romney walked past McConnell. “They nailed him,” McConnell remarked, according to Romney.

Romney, taken aback, said that Trump’s team could spin his misconduct to make it appear as though he was just investigating the Biden family’s corruption.

“If you believe that,” McConnell reportedly replied, “I’ve got a bridge I can sell you.” The Senate leader told Coppins that he did not recall this exchange, and it did not match his thinking at the time.

Romney messaged McConnell to warn him about the Jan. 6 attacks. McConnell didn’t reply

On Jan. 2, 2021, Romney got a heads-up from another senator who’d spoken to a senior Pentagon official, warning him about extremist threats that law enforcement had been tracking in connection to protests planned for Jan. 6.

Romney passed on the concerns to McConnell, texting him, “There are calls to burn down your home, Mitch; to smuggle guns into DC, and to storm the Capitol. I hope that sufficient security plans are in place, but I am concerned that the instigator—the President—is the one who commands the reinforcements the DC and Capitol police might require.”

McConnell never wrote back, according to Coppins.

Romney really, really hates Josh Hawley and J.D. Vance

Over his four years in the Senate, Romney accrued a special kind of loathing for Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO) and Sen. J.D. Vance (R-OH). During the Capitol riots, while huddled in the Senate chamber with his colleagues, Romney recalled whirling on Hawley to yell at him that this was his fault.

“They know better!” he told Coppins of his far-right colleagues. Granting that Hawley was “one of the smartest people in the Senate, if not the smartest,” Romney speculated that the Missouri lawmaker had made “a calculation” that ended up putting “politics above the interests of liberal democracy and the Constitution.”

Having lost the stomach for collaborating with his more Machiavellian counterparts, Romney at one point over the last two years outright told Coppins that he doubted he would ever “work with Josh Hawley on anything.”

Last year, Vance similarly stoked Romney’s ire. Initially a fan of Vance’s memoir Hillbilly Elegy, Romney turned on Vance after his “MAGA makeover,” as Coppins put it. Watching Vance rail against Biden and the woke left on the campaign trail, Romney said, he wanted to grab the younger man and scream in his face that debasing himself like this wasn’t worth it.

“It’s not like you’re going to be famous and powerful because you became a United States senator,” Romney said. “It’s like, really? You sell yourself so cheap?”

Romney approached Joe Manchin about forming a new party

In April 2023, Romney went to Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), one of his few allies, with a pitch to form a more centrist party. He didn’t have a name yet, but he did have a slogan: “Stop the stupid.” His idea wasn’t to run a candidate themselves, but to endorse the least objectionable of the candidates already shooting for the White House.

“We’d say, ‘This party’s going to endorse whichever party’s nominee isn’t stupid,’ ” Romney told Coppins.

It was not immediately clear from the extract how far they got; Coppins writes that the last time he spoke to the Utah senator about the idea, he was “still in the brainstorming stage.”

A largely friendless Romney binged Ted Lasso alone in his $2.4 million townhouse at night

In early 2019, days before being sworn in as senator, Romney wrote an op-ed for The Washington Post criticizing Trump. It would immediately set the tone for his time on Capitol Hill; in a story published shortly after, Politico noted he’d been receiving a “chilly reception” from his fellow Republicans. Romney emailed the story around to his staff, labeling himself “the turd in the punch bowl.”

Coppins writes that Romney never made many “real friends” in Washington. By fall 2019, he’d come to dread the weekly caucus lunches, which made him feel like a teenager navigating high school cliques again. “I mean, it’s a funny thing,” he said. “You don’t want to be the only one sitting at the table and no one wants to sit with you.”

He was frequently without his family on his trips to the capital, as well. Ann Romney and his five sons rarely visited D.C., and the expensive townhouse that the senator had purchased gradually fell into a state of bacherloresque disrepair. Coppins writes of crumbs on counters and a fridge stocked solely with sodas and seltzers. (Romney, a lifelong Mormon, does not drink alcohol.)

For dinner, Romney would often turn to the slabs of frozen salmon packing his freezer—gifts by way of Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK). The senator would throw together his own form of “girl dinner,” shoving the salmon on a hamburger bun and slathering the whole thing in ketchup. Then he’d sit down in his leather recliner and switch on Ted Lasso or Better Call Saul, idly going through briefing materials while eating.

Romney is haunted by the specter of his own death

The 76-year-old senator is preoccupied with the subject of death, according to Coppins. His retirement was partially prompted by this fixation. He speculates that he has about a dozen-odd years left, if his family history (littered with sudden instances of heart failure) is anything to go by.

“Do I want to spend eight of the 12 years I have left sitting here and not getting anything done?” he asked.

Romney has been bizarrely confronted with the notion of his own death a few times before. On a flight to London a few years back, he recalled, an attendant he’d never met before looked at him, audibly gasped, and fled the cabin.

Asked what had so horrified her, the crew member explained that she’d dreamed about a man who might as well have been Romney’s doppelgänger the previous night. She’d watched the double get shot and killed at a rally in a park. Romney had laughed. But when, a few days later, he walked past the park in question and saw a crowd, he’d quickly moved on.

It’s not clear if that encounter had ever crossed Romney’s mind in the weeks and months before Jan. 6, as the threats and harassment he received rose to such a level that his wife begged him not to go back to Washington on the day of the attacks.

If it did, he didn’t betray it. Don’t worry, he’d joked to her. “If I get shot, you can move on to a younger, more athletic husband.”