Janii Van Doten of the Bronx was doing her murdered son’s laundry Wednesday afternoon when Mayor Michael Bloomberg called to offer his condolences.

Her 17-year-old son, Alphonza Bryant, had been killed by a stray bullet April 22, and Bloomberg had spoken of his death during a speech at NYPD headquarters Tuesday. Bloomberg had said it was exactly the kind of tragedy the police are trying to prevent with a stop-and-frisk policy that has been the subject of a lawsuit filed by the ACLU and topic of contention among those vying to become his successor.

Bloomberg had noted during his remarks that The New York Times had described the tactic as “widely loathed.” He also had observed that “our paper of record” had not covered Bryant’s death.

“Let me tell you now what I loathe. I loathe that 17-year-old minority children can be senselessly murdered in the Bronx, and some of the media doesn’t even consider it news,” Bloomberg had said.

The Times has been running some fine articles about the Bronx courts and had posted a New York Daily News report of the shooting, so it could not rightly be accused of total indifference to the borough. There was still no disputing the answer Bloomberg furnished to the question he then posed.

“Do you think if a white, 17-year-old prep school student from Manhattan had been murdered, the Times would have ignored it?” he asked. “Me, neither.”

Van Doten had been surprised and pleased when she learned that the mayor had mentioned her son in his speech. She thanked him now over her cellphone as she stood in the Clean and Bright Laundromat on Prospect Avenue.

“He just told me he’s going to do everything in his power to not have this happen anymore,” she reported afterward. “I told him this is not the first time, this is not going to be the last. It is going on forever and forever and forever. It’s not going to stop until we get the illegal guns off the street.”

Her cellphone back in the pocket of her yellow sweater, Van Doten returned to the clothes that had been in her son’s laundry bag in his room after his death. She was not going to throw them way or just leave them unwashed.

“Wash it and just put it away in the drawers,” she said.

She is said by all in the neighborhood to be a genius mother, and one mark of it is that she had sought to instill a sense of personal responsibility early on by having her son do his own laundry, starting when he was in grade school.

“This is the first time since he was 10 I do his laundry,” she said. “Under the circumstances, I don’t mind.”

The laundry had been part of a larger pact in which she bought him whatever clothes and sneakers that were within her means as long as he kept up his schoolwork and did as she told him. He had kept up his end by earning high grades and coming home by his 11 p.m. curfew.

“I did right by him,” she said. “In my heart I know I did all I could do with what I had. He was satisfied with it.”

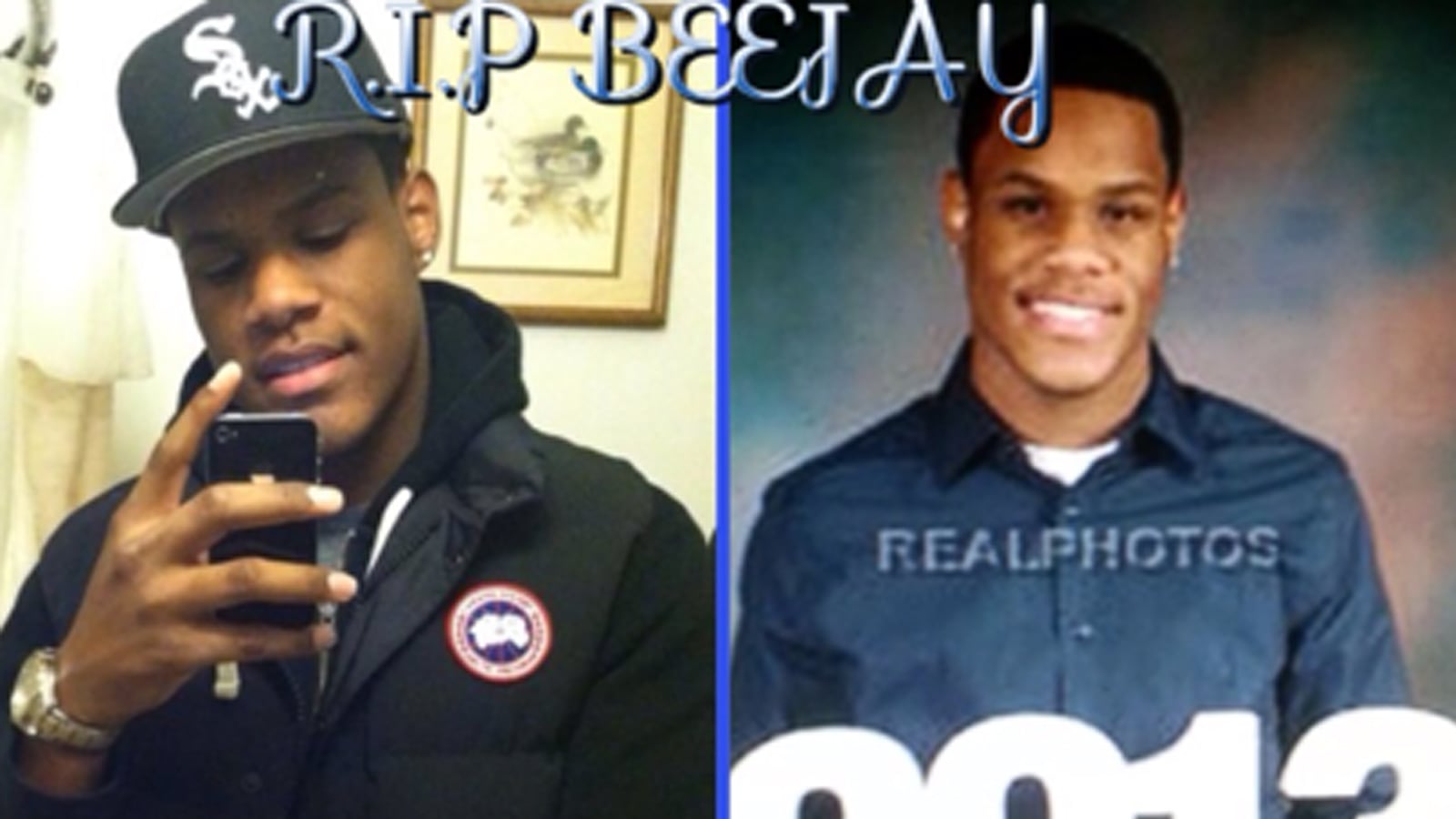

As she spoke of him, she often called him by his nickname, BeeJay, which was derived from Born Jr. His father, also Alphonza Bryant, had been nicknamed Born. The father had been shot to death in the Bronx in 1999, a fortnight before the son’s fourth birthday.

“Two different eras, two different lives, and yet died the same way. How is that possible?” the mother said. “They died with one thing in common—illegal gun violence.”

She derived no comfort from numbers saying that since the father's death, New York has become the safest big city in America.

“I don’t know the statistics, but I do know my kid was a good kid, and he didn’t deserve to die,” she said.

She made an observation about how things remain.

“It’s easier to get a gun than it is to get a job,” she said.

She herself has a union construction job. She said her son had just obtained an application for his very first job, at a local fast-food place. She took out her cellphone again to show a reporter a text he had sent her at 4:09 p.m. April 22.

“Do I take the application?”

She knew the man who owns the franchise, and she figured it might be better if she took it in, at the same time saving her son the trouble of trekking there. She texted back.

“No. Wait. Clean that room.”

When she returned home, her son had gone to hang out with friends on nearby Fox Street, but his bed was neatly made, and the room was immaculate. He was shot at 8:10 p.m., four hours and one minute after sending that text. She was left to wonder if things might have been different had she not told him to wait.

“Maybe if I’d said go ahead ...” she now began to say. “It will always be in the back of my mind.”

Her thoughts of seeing him in the afterlife were joined by a worry.

“I just hope he’ll forgive me,” she said. “I just hope that kid will forgive me.”

She was ready to support any effective strategies that lead to fewer shootings. There is no doubt that stop and frisk has reduced the number of guns on the street and therefore saved lives, perhaps hundreds, maybe more.

But she also believes that the strategy could be modified to make it more effective. She gained insight into some of the flaws some months ago, when she got a call from her son on the same phone the mayor had just called.

Bryant had gone with friends to the 20/20 Deli on Southern Boulevard to get some sandwiches. He stepped outside while they waited, and the police decided he was a candidate for what would officially be termed a stop and frisk. It was in truth more of a stop, curse, and search far beyond a pat-down that would have detected a gun.

“They were going in his pockets, in his shoes,” said his friend, 18-year-old Jose Castillo. “They were even in his hat.”

Bryant’s mother had always told him that if he was stopped by the police, “just be who you are,” but that was not helping much. His friends knew that he had a protector who would do anything for him.

“BeeJay, call your mom!” they called out.

Bryant managed to call, and she answered to hear not just her son, but a cop shouting at him. The words were coming as clearly to her as she would later hear Bloomberg.

“Get the fuck off the phone!”

Bryant told the cops, “Yo, chill, that’s my mom.” He told his mother, “I got to get off the phone. I got to get off the phone.”

The friends say Bryant had the presence of mind to put the phone on speaker, so the cops heard the voice of pure MOM.

“I’m coming right now!” she announced.

The words had an immediate effect. The cops had departed and allowed Bryant and his friends to go on their way by the time the mother had hopped into her gray Pontiac and driven the few blocks to the deli.

But it is to everyone’s sorrow that no cops stopped and frisked the duo who came ambling up Fox Street just after 8 p.m. April 22. They walked past where Bryant and some friends were standing and then circled back. One of them for some reason began shooting.

A 17-year-old named Jonathan Nieves who had been hit in the leg by a stray round in July was standing next to Bryant and began running. Bryant fell and struggled to drag himself under a car as the shooting ended. Bryant was a famous joker, and Nieves thought maybe he was just playing.

“Then I saw the puddle,” Nieves remembered.

Nieves meant the blood. Bryant was famous for standing with his arms crossed, and a bullet had struck his armpit and pierced his chest. A friend began desperately trying to stop the bleeding. He was joined by an off-duty nurse from across the street.

On Wednesday afternoon the friends were still in a state of shock. They stood by a makeshift shrine where their friend had been fatally wounded. People had brought candles and two floral displays, a cross and a heart. Somebody had spelled his nickname on the pavement with blue wax.

Bryant’s pact with his mother had resulted in him becoming a perfect example for his friends. He had nice clothes, but he had earned them with stellar report cards.

“A-, A+,” 22-year-old Rafael Perez said. “He worked for everything he got.”

A few days before the shooting, he had asked his friend Castillo what he should study when he started community college in Manhattan in the fall. Castillo asked what he wanted to go into, and Bryant said he thought architecture, but he was not completely sure.

“I said the best thing you could do is liberal arts and get a little bit of everything,” Castillo recalled.

But as serious as he was about his schoolwork, Bryant remained an unfailingly fun guy.

“He always had a way to make people smile,” Castillo remembered. “He always made us laugh. We never had a bad moment with BeeJay.”

Castillo and the others reminisced about how Bryant had been a short and chubby kid and then suddenly grown tall and lean and handsome. He always was a trendsetter, not a follower in fashion, but what made him excited about getting his first job was not that he would have more money to spend on himself.

“He always said his mom did so much for him, he wanted to start giving back to his mom,” Castillo said.

Now Bryant came to them in their dreams, waking them repeatedly.

“Six to five times a night,” Castillo said.

The talk turned to what might have been done to prevent the shooting.

“I think the stop and frisk is good, but at the same time it isn't,” Perez said.

Perez suggested that a lot of the problem is the way the police conduct the stops. He spoke in a “proper, polite” way he feels a cop should on approaching someone.

“Excuse me, citizen, we have to stop and frisk. We’re not trying to blame you for anything.”

Perez is in the meantime so shaken by the shooting that he enlisted in the Army on Tuesday with the hope of just getting away.

The mother was over at the Clean and Bright, folding the last of her trendsetting son’s clothes. She said 500 people had come to the funeral.

“We danced in the middle of other street for him, and the police let us have our moment,” she recalled.

On hearing that her son’s friends were dreaming of him, she said, “That means he’s with them. My kid, he didn’t come to me yet. But I did feel him hug me the night of the service.”

She had gotten his likeness tattooed on her upper arm, and she raised her sleeve to show it to a reporter.

“It hurts,” she said. “Does it look like him?”

It did. His senior-year photos had come the day he was killed, and he had already been fitted for his prom tuxedo. His mother would still be attending his graduation.

“And I’m going to his prom with his prom date,” she said.

She was nearly finished with the laundry.

“Keeping me busy, keeping me concentrating on something,” she said.

She would then take it home and place it in the drawers.