I remember him every day of my life. I especially remember him this time of month because Abe Rosenthal died in May. And this May I remember him even more—and I miss him deeply—because I’m marking a big birthday this month, the same month that Abe was born. It is the kind of birthday that one knows would be inevitably on the calendar, but never expects that it’d arrive so soon. Where did all the years go, and why did they slip by so fast? Why did someone not stop the clock?

I do not celebrate my birthdays, because they are mere markers and not milestones for me. I do, however, always think of my parents, Dr. Charusheela Gupte and Balkrishna Gupte, because, of course, they were there in Bombay when I arrived in this world. They have been gone for 28 years—and I remember them every day of my life, too, just as I remember my maternal uncle, Keshav Ramachandra Pradhan, who helped raise me because my mother’s career as a professor, writer and social activist kept her away from home a lot, and my father’s job as a lawyer at a bank had him working long hours.

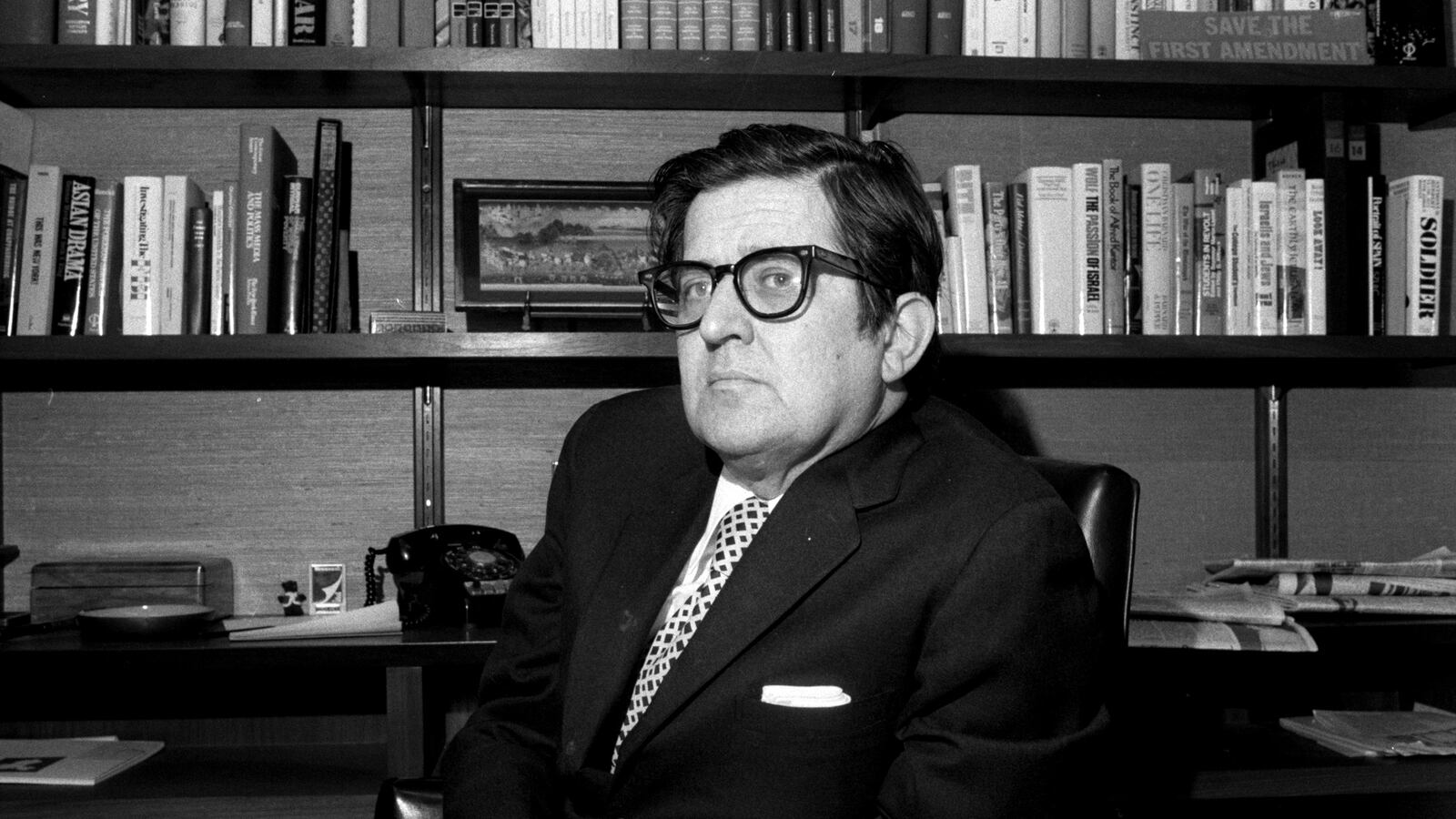

Abe Rosenthal—A. M. Rosenthal was his legendary byline—has been gone for only six years, dead at 84. But it was he who brought me into a different kind of life, into international journalism. He hired me at the New York Times while I was still at Brandeis University in the United States, a slip of a boy with outsized ambitions that he relentlessly encouraged me to pursue.

Abe appreciated ambition. After all, it was ambition that had driven the Canadian-born Abe from an impoverished childhood in which he suffered from osteomyelitis, a bone-marrow disease in his legs, to the most powerful position in global journalism: executive editor of the New York Times. Along the way, he made a name for himself as a foreign correspondent who wrote in an emotional and personal style that ran against the grain of The Times’ conventionally colorless prose. He won the Pulitzer Prize for his courageous reporting from Poland when a brutal Communist regime was in power.

But Abe Rosenthal cherished his time in India the most. It had been his first overseas assignment, and it was in the heady years soon after Independence when India seemed destined for great things under the leadership of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. It was, Abe wrote, a time of “high adventure.”

By hiring me Abe offered a chance to participate in a different sort of high adventure—the newspaper narrative. He sometimes quoted Irwin Shaw, the great novelist: “There is the reward of the storyteller, sitting cross-legged in the bazaar, filling the need of humanity in the humdrum course of the ordinary day for magic and distant wonders, for disguised moralizing that will set everyday transactions into larger perspectives, for the compression of great matters into digestible portions, for the shaping of mysteries into sharply edged and comprehensible symbols. Then there is the private and exquisite reward of escaping from the laws of consistency. Today you are sad and you tell a sad story. Tomorrow you are happy and your tale is a joyful one.”

Storyteller in the bazaar; what a compelling phrase, what a compelling image. That’s how I saw myself when I first heard those words from Abe Rosenthal, and still do. Abe taught me that it was all right to write personally, and that what mattered truly was that a reporter caught the emotions of those whose stories he told. Everyone had a story to tell, Abe would say, you just had to listen carefully and take it all down. Every little detail counted because a person’s story was a mosaic of those details; a man’s story was a sum total of many episodes.

Of all the stories that Abe Rosenthal filed as a foreign correspondent, the one that moves me most is a 700-word dispatch after a visit to Auschwitz, the camp in Brzezinka, Poland, where the Nazis murdered thousands of Jews in gas chambers.

Abe wrote, in part: “The most terrible thing of all, somehow, was that at Brzezinka the sun was bright and warm, the rows of graceful poplars were lovely to look upon, and on the grass near the gates children played. It all seemed frighteningly wrong, as in a nightmare, that at Brzezinka the sun should ever shine or that there should be light and greenness and the sound of young laughter. It would be fitting if at Brzezinka the sun never shone and the grass withered, because this is a place of unutterable terror.

“And yet every day, from all over the world, people come to Brzezinka, quite possibly the most grisly tourist center on earth. They come for a variety of reasons—to see if it could really have been true, to remind themselves not to forget, to pay homage to the dead by the simple act of looking upon their place of suffering.”

He concluded: “And so there is no news to report from Auschwitz. There is merely the compulsion to write something about it, a compulsion that grows out of a restless feeling that to have visited Auschwitz and then turned away without having said or written anything would be a most grievous act of discourtesy to those who died there … There is nothing new to report about Auschwitz. It was a sunny day and the trees were green and at the gates the children played.”

I choke every time I read those words. I choke even as I reproduce them here. Simple prose, yet so powerful.

So on this big birthday, I ask myself, inevitably: Have I faithfully led the kind of journalistic life that Abe sketched out for me? After all, journalism is the only thing that I have done in my long years. Abe blessed me with his mentoring – how many journalists and writers are so fortunate? He taught me, most of all, about the power of words. He taught me the art of story telling.

Abe Rosenthal gave me the biggest gift I ever received well before this big birthday of mine. That’s why I remember him today, and I miss him so very much. I remember him because I have so many more stories to tell in the bazaar, and I have less and less time with every birthday.