A new theory about the fate of Amelia Earhart is seriously undermined by evidence obtained by The Daily Beast. The theory, to be aired Sunday in a History Channel documentary, claims that Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, were rescued by the Japanese after crash landing in the Marshall Islands and then taken to a Japanese prison where they died in captivity.

The pivot of the documentary’s case is a photograph, undated, of a wharf at Jaluit Island, one of the scores of atolls that make up the Marshall Islands. A forensic expert who specializes in facial recognition appears in the program to support the claim that Earhart and Noonan are among a group of people on the wharf.

Just beyond the wharf, in the harbor, is a Japanese military vessel identified as the Koshu Maru. The documentary suggests that after this picture was taken Earhart and Noonan were arrested and taken aboard the Koshu Maru and that a barge alongside contained the remains of their Lockheed Electra airplane.

According to the documentary, it is likely that the Koshu Maru then sailed for the island of Saipan where the two Americans were imprisoned and then killed.

The role of the Koshu Maru (maru means ship in Japanese) is therefore crucial to the theory that Earhart and Noonan are, indeed, the people in the photograph.

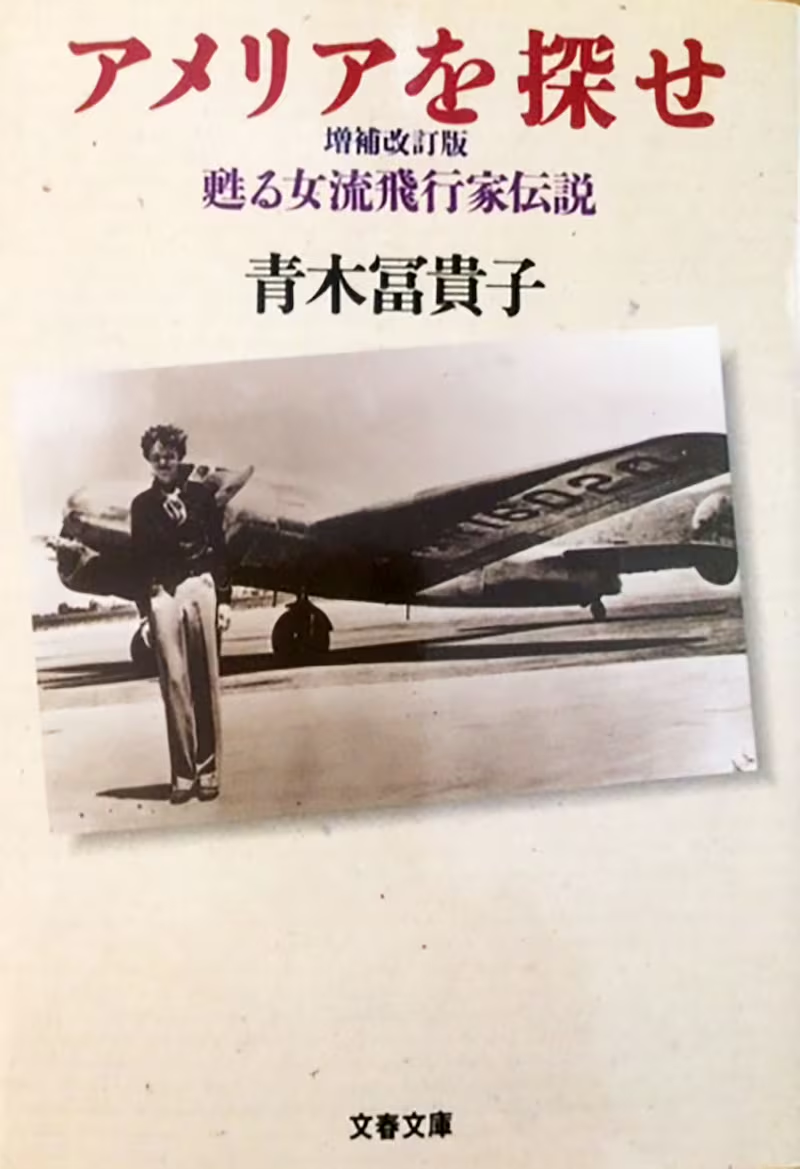

However, in 1982 a Japanese author and journalist, Fukiko Aoki, published a book in Japanese, Looking for Amelia. She found a surviving crewmember of the Koshu Maru, a telegraphist named Lieutenant Sachinao Kouzu. He told her that, like other Japanese ships in the western Pacific, they were told that Earhart had disappeared while over the ocean and were alerted to look out for any sign of the airplane and, if they did, seek to rescue Earhart and Noonan.

After a few days, said Kouzo, the alert was dropped. At no time did anyone on Koshu Maru set eyes on the Americans, alive or dead.

Aoki told The Daily Beast that her interest in the Earhart story was sparked when she read a story about four Japanese meteorologists who were assigned to a weather station on Greenwich Island in the South Pacific. As soon as they arrived at the station early in July 1937, they received a government message to look out for the aviators and, if they saw them, to organize a rescue operation. They saw nothing.

“The disappearance of Amelia Earhart looks so different from the Japanese and American sides,” Aoki told The Daily Beast. “One of the weathermen, an old guy called Yoneji Inoue, protested against the theory that Amelia was captured and executed by the Japanese. I wanted to find out what really happened. I found and checked the log of the Koshu Maru, but of course I couldn’t find any description of the capture of Amelia Earhart.”

Aoki later moved to New York where she became bureau chief for the Japanese edition of Newsweek. She has written 12 books. Looking for Amelia was republished as a paperback in 1995 but only in Japanese.

The four meteorologists were taken to Greenwich Island on the Koshu Maru, arriving on July 3, the day after Earhart disappeared. Greenwich Island is now named Kapingamaranji,and is 1,500 miles from the Marshall Island where the photo supposedly of Earhart was taken, which means that the vessel was nowhere near the Marshall Islands at the crucial time.

As Aoki’s research indicates, the assumption that the Japanese military was under orders to arrest and quietly kill Earhart and Noonan them shows little understanding of what was happening in the Pacific at the time.

The war in the Pacific didn’t begin with Pearl Harbor. It began on July 7, 1937, five days after Earhart disappeared, when a minor clash between Japanese and Chinese troops near Beijing suddenly turned into all-out war between the two nations.

The last thing the Japanese needed was to inflame American opinion by murdering the world’s most-famous woman. Although they had a formidable air force and navy the Japanese were distracted by Soviet Russia’s claims to Japanese islands and at that time they also feared American naval power in the Pacific. America, in turn, wanted no part of the war in China.

Just how anxious both the U.S. and Japan were to avoid conflict was revealed by an incident in December 1937. An American gunboat, the USS Panay, that was allowed to patrol the Yangtze River by international agreement, was called in to evacuate staff from the U.S. embassy in Nanking, as well as some international journalists as the Japanese carpet-bombed the city.

The Panay sailed upriver to what the captain thought would be a safe refuge and anchored alongside other boats laden with Chinese refugees.

But a swarm of Japanese bombers attacked all the boats, including the Panay. Two U.S. crewmen and an Italian journalist were killed. The Japanese claimed that the attack was an accident. President Roosevelt was so anxious that the bombing should not lead to calls for retaliation that he censored newsreel footage. The Japanese, alarmed that they might have awakened a sleeping tiger, paid $2.2 million in compensation.

Then there is how the Japanese treated Charles Lindbergh.

In August 1931, he flew from Alaska across the Bering Sea to Japan in a seaplane with his wife Anne. Thick fog forced Lindbergh to make a blind landing using only his instruments. After touchdown, with the engine shut down, the airplane drifted dangerously close to rocks and was rescued by a Japanese boat that towed them to a safe harbor.

When they reached Tokyo the Japanese gave the Lindberghs a welcome that one newspaper said was “one of the greatest demonstrations ever seen in the ancient capital.”

As for Earhart, there was no military intelligence value to the Japanese in getting their hands on her Lockheed Electra. The Electra was widely used by airlines across the world and held no technological secrets. By 1937 the Japanese were mass-producing a Mitsubishi bomber so far superior to the similarly-sized Electra that when it was converted to an airliner it flew a record-breaking round-the-world flight.

The theory that Earthart crash landed in the Marshall Islands is not supported by the basic rules of geography and navigation. It rests on the idea that, once Earhart realized she had missed a scheduled rendezvous with a U.S. Coast Guard cutter on tiny Howland Island, she reversed direction.

The Marshall Islands are 800 miles northwest of Howland Island, way beyond the range of the Electra as it was running low on gas at the end of a long leg from Papua New Guinea, over the Pacific.

Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan's 1937 World Flight Attempt

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily BeastHer only option was to look for a landing place that was much closer and, ideally, ahead of her rather than far behind.

Her last message to the cutter was at 8:43 a.m. on July 2. It was that she was flying on a line of 157 337 – that is, the southeasterly course from her starting point that intersected Howland Island. Because of an unexplained problem with the Electra’s radio, the cutter could receive her messages but she couldn’t receive the replies.

As a result, in the 80-year search for Earhart there is nothing to go on to point to her final position beyond what was in that radio transmission. Yet on the basis of that one transmission we arrive at the next most prominent theory about Earhart’s fate.

This takes us to an atoll named Nikumaroro Island, 350 miles southeast of Howland Island, and to Ric Gillespie, chief executive of The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery, TIGHAR.

Gillespie is the best funded and most persistent of all Earhart hunters. Since 1989 he has directed 12 expeditions to Nikumaroro, partly funded by National Geographic, and each expedition follows the same pattern: advance publicity that garners a gullible audience and funds, followed by negligible results, some bordering on the ludicrous.

Gillespie gave scientific credence to his theory by analyzing 120 reports of radio traffic in the area of Nikumaroro at the time and deciding that 57 messages were possibly transmitted from the Electra, beginning three hours after the final transmission picked up by the Coast Guard cutter.

To believe this demands two leaps of faith or, more likely, of the imagination. The first is that Earhart managed to land on the atoll and the second is that she did so with such skill that her radio remained able to operate.

Such a landing would have required a near miraculous feat of airmanship. Nikumaroro is a typical coral atoll sitting atop a volcano with a rocky reef looping around a lagoon with only a tiny appendage of flat surface. And although she did not lack courage, Earhart was not a pilot of natural intuitive skills, like Lindbergh, and the Electra was an unforgiving machine in a marginal situation like this.

Satellite image of Nikumaroro Island.

TIGHAR / Barcroft USA /GettyEarhart, under the stress of knowing that her fuel was running out, would have had to align her approach over water at a shallow angle and make a finely-judged touchdown with no margin of error. Landing on an aircraft carrier would be much easier.

For the radio signal theory to have any credence the airplane then had to remain undamaged by water – for days.

For a fraction of the money that TIGHAR has invested and is still investing in its expeditions they could have commissioned a computer program to simulate the landing. All the necessary data about the handling characteristics of the Electra and the probable weather and sea conditions at the time are available. The trouble is, of course, that this would prove the impossibility of the idea.

Gillespie was, not surprisingly, dissed when told of the History Channel “revelation” about the Marshall Islands.

“This is just a picture of a wharf at Jaluit with a bunch of people, it’s just silly,” he said.

This happened when Gillespie had just sent another expedition to Nikumaroro, this time including four sniffer dogs trained by the Institute for Canine Forensics. The dogs arrived wearing life vests when the temperature was more than 100 degrees. They were looking for human remains – the latest spin of the theory being that Earhart and Noonan had perished there.

The Earhart saga will go on providing endless fuel for lovers of the classic vanishing airplane narratives. People in the grip of a pet theory will go to great lengths to believe in that theory on the thinnest evidence. Gillespie, for example, seized on the discovery of a jar of 1930s ointment for the treatment of freckles found in the waters near Nikumaroro as evidence that Earhart, famously freckled, had made it to the island.

Freckles would not have been of much concern as Earhart planned her flight. Nothing that was not essential was carried in the Electra. She was piloting what was virtually a flying gas station. In place of passenger seats the airplane was stuffed with six large extra gas tanks and had another six in the wings, as well as having to carry 80 gallons of oil for its hot-running supercharged engines.

There is, to be sure, no reason to stop looking for Earhart, Noonan and the Electra. The odds are that after a desperate search for land they ended up, out of fuel, ditching into the ocean, and then plunged as far as 17,000 feet down to the bottom of the ocean. They most certainly didn’t die in a Japanese prison.