1923 was the year of the first “Marathon Dance,” the endurance contest in which couples dance until they fall over from exhaustion. Miss Alma Cummings won the inaugural competition, held in New York City, after staying on her feet for twenty-seven hours. The contest quickly caught on nationally and Cummings was bested the next month by a dancer in Cleveland who lasted ninety hours and ten minutes. Not long after that, a man in North Tonawanda, NY, after shuffling his feet for eighty-seven hours, earned a different distinction—he was the first Marathon dancer to drop dead on the dance floor.

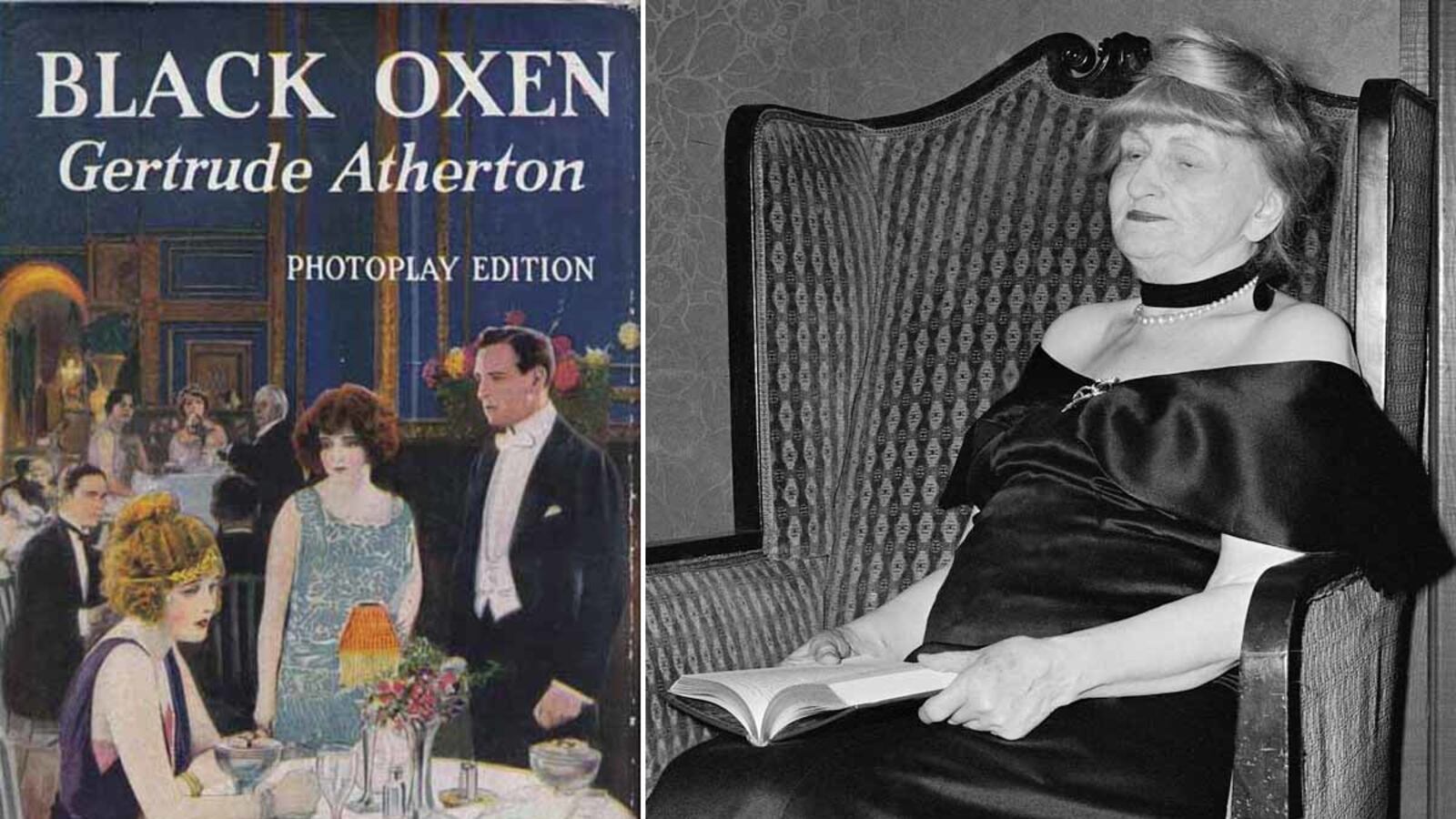

But everyone kept dancing. After the recession of 1921-1922, the country had entered an era of unrestrained economic growth. The jazz age was in full swing and the so-called “younger generation,” whose poets and artists called themselves the “lost generation,” was ascendant. A novel published in 1920 by a twenty-four-year old F. Scott Fitzgerald, This Side of Paradise, brought to national attention the impetuousness and licentiousness of this new generation. “The decade,” as Mark Sullivan wrote in Our Times, “was the decade of the young.” Yet the best-selling novel of 1923 was written by the 65-year-old Gertrude Atherton, an author best known for her historical novels and short stories about California, some of them published more than three decades earlier. Atherton had drawn her novel’s title, Black Oxen, from a line in W.B. Yeats’ verse drama, The Countess Cathleen:

“The years like Great Black Oxen tread the worldAnd God the herdsman goads them on behind.”

Youth is Atherton’s subject—both the ascendance of the younger generation and the decline of the generation that, by the early 1920s, was fading into obsolescence. But Atherton didn’t share the reverence for the youth coming up behind her. The enormous success of her novel suggests that by 1923 much of America had had enough of Fitzgerald and wished his generation would just get lost already.

The scene is Manhattan in the Roaring Twenties. Women of means—and all the novel’s women have plenty of means—wear diamond tiaras, large fans of green feathers, soft gray coats trimmed with blue fox, and lots of mauve, “the fashionable color of the season.” Upper East Side apartments contain Louis Quinze rooms bedecked in furniture that appears to be made of solid gold. Characters are constantly glancing up from their oysters, or fretting about their steak being overcooked. The diet, in fact, is so rich and plentiful, that gout is a common condition. Even unmarried novelists are able to purchase Manhattan brownstones.

Atherton’s hero is Lee Clavering, a young theater columnist and aspiring playwright with high connections and higher ambitions. As a leading member of the Sophisticates—Manhattan’s young intellectual set—Clavering attends Broadway premieres and society parties every night, transferring himself “from one woman’s side to another’s by sheer effort of will spurred by boredom,” and dancing—or “jazzing.” Atherton is too demure to disclose whether the Sophisticates violate the Eighteenth Amendment, but the novel gives off a heady whiff of gin.

Clavering’s boredom is interrupted when he notices a mysterious stranger, an elegant woman with strange blonde hair “the color of warm ashes.” His older friends are stunned, for the blonde woman looks exactly like Mary Ogden, a woman who in their day was the belle of Manhattan. But Mary vanished three decades ago, after marrying a Hungarian diplomat, and she had not been seen since. Could this woman be her daughter?

After nearly two hundred pages, and countless cocktail parties and gossipy luncheons, we learn that the mysterious woman is Mary Ogden herself. In Vienna she had undergone a new medical process, involving her endocrine glands, that rejuvenates the body and skin. Though actually 58, Mary doesn’t look a day over 28. She is surprised by her friends’ reaction—the Europeans, we learn, have known about the aging cure for years. Still the novel stops short of total fantasy—though Mary looks young, her life has not been prolonged. She has had, in other words, the equivalent of excellent plastic surgery.

Clavering is undeterred, but Mary wavers. She loves Clavering, but love, she decides, is not enough. It is a jarring plot twist—the comedy formula demands a happy marriage resolution, but Mary instead abandons Clavering and returns to Vienna where, by reuniting with her former husband, a prominent statesman, she might “save Austria” and become “the most famous woman in Europe, and perhaps the most useful.” (What exactly she will do in Vienna is never made explicitly clear, just that it will be very important.) Should she stay in New York with the young playwright, she would forfeit everything. A truly modern woman, Mary chooses empowerment over love. Whimpering Clavering is abandoned. The end.

“I cannot ... go back,” says Mary, elsewhere in the novel. “One cannot paint and read and walk and motor and dance all the time.” Though her skin has rejuvenated, her mind has grown wiser with time. She knows that the passions of youth, while transporting, lead nowhere. Booms lead to busts. The music stops, and the dancers begin to drop dead. Black Oxen is a reminder of the healthy benefits of cynicism, and in retrospect served as an early warning to an ebullient age. Even as the Twenties roared, Atherton, and her many readers across the country, were roaring back.

Other notable novels published in 1923:

Many Marriages by Sherwood AndersonA Lost Lady by Willa CatherThe Florentine Dagger by Ben HechtBread by Charles G. NorrisCane by Jean Toomer

Pulitzer Prize:

One of Ours by Willa Cather

Bestselling novel of the year:

Black Oxen by Gertrude Atherton

About this series:

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2013. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers.

Previous Selections:

1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon 1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson1922—Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis 1932—Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell 1942—A Time to Be Born by Dawn Powell 1952—Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison 1962—One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey 1972—The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin1982—The Mosquito Coast by Paul Theroux1992—Clockers by Richard Price2002—Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides2012—Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain1903—The Call of the Wild by Jack London1913—O Pioneers! By Willa Cather