“To hell with stockings,” said Mrs. Copperfield, who thought she was about to faint. “Let’s get some beer.”

Two Serious Ladies is a spectacular enigma of a novel. It shouldn’t work; by any conventional criteria, it doesn’t work. The characters are inscrutable, the plotting careless, and, at every opportunity, Bowles subverts the dramatic stakes. In the novel’s final line, she describes her main character’s evolution as being “of considerable interest but of no great importance.” But the language is mesmerizing. Each sentence is like a viper, coiled in on itself and ready to bite. Stylistically Jane Bowles resembles her own heroine, Miss Goering, to whom another character complains, “you can never sit down for more than five minutes without introducing something weird into the conversation. I certainly think you have made a study of it.”

Over the years Bowles has been called the “the most important writer of prose fiction in Modern American letters” (by her friend, Tennessee Williams); a “modern legend” (another friend, Truman Capote); a “mistress of the elliptical, an angel of the odd” (Joy Williams). Her work is a literary Rorschach test. Frequently she has been cursed with the designation, “a writer’s writer”; John Ashbery went further, calling her “a writer’s writer’s writer.” Capote classified her as “a humorist of sorts,” while her husband, the novelist Paul Bowles, described her work as “like the unfolding of a dream.” Francine du Plessix Gray and Stacey D’Erasmo, among others, have claimed her for feminist and lesbian literature, respectively. Lost in all of this is the fact that Bowles’ only novel was published in the middle of World War II.

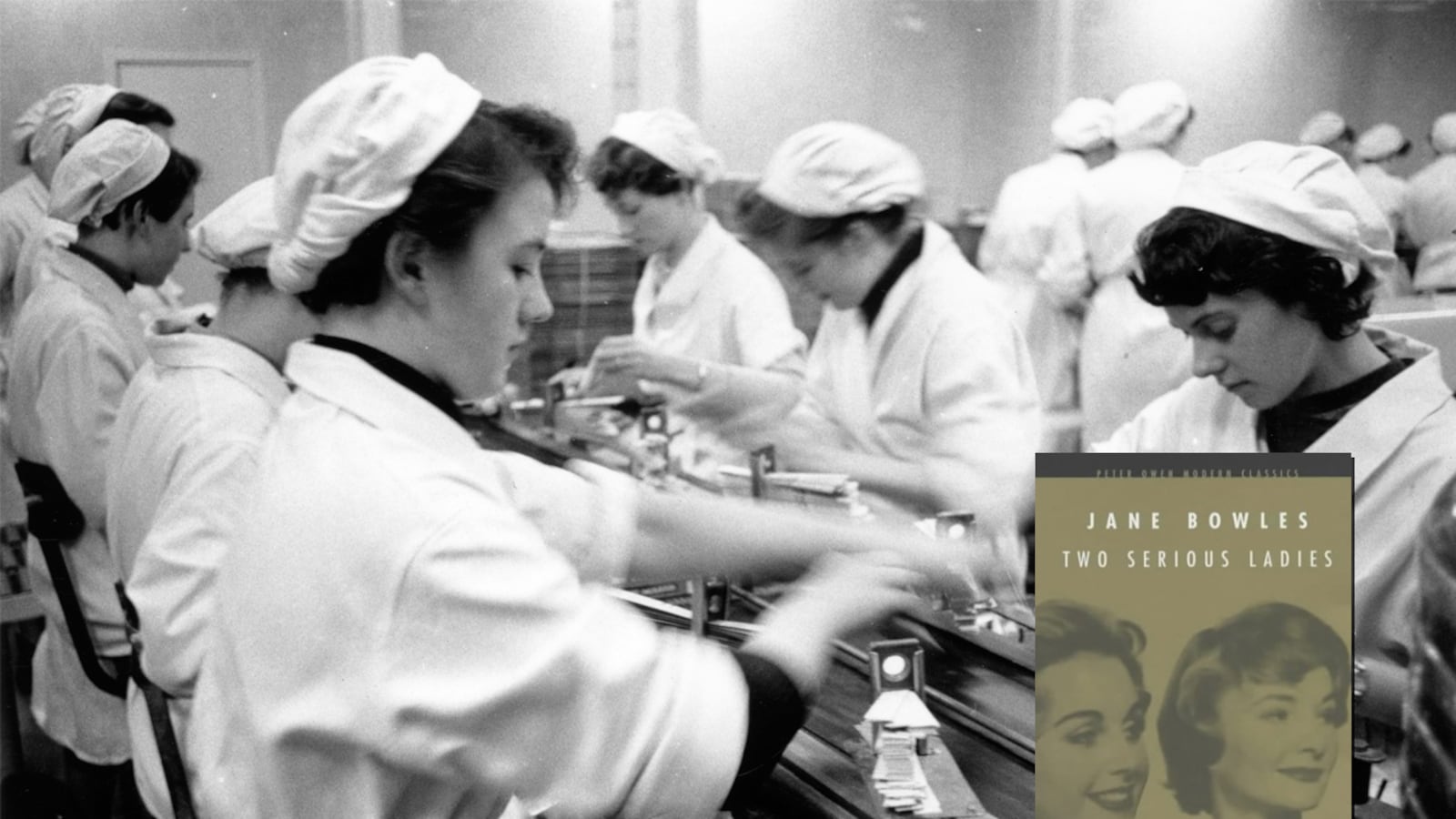

It is true that, for the first time in a generation, the role of women in American society was undergoing a profound transformation. During the war the number of employed women had increased by nearly sixty percent. Women were hired for industrial jobs that previously had been reserved for men, joined unions in substantial numbers, and had begun to challenge ancient biases, such as the one that married women couldn’t work, or that a single woman was incapable of supporting herself. But this isn’t the kind of liberation that Bowles’ characters seek.

Her serious ladies are uncomfortable in their skin; neither of them are quite “under control.” Christina Goering is a “wild and peculiar” young women from a distinguished New York family who lives alone in what appears to be Staten Island. Most people find her “a little disturbing,” on account of her “red and exalted face and her outlandish clothes.” She wears “the look of certain fanatics who think of themselves as leaders without once having gained the respect of a single human being.” A modern diagnosis would be depression. “I wanted to be a religious leader when I was young,” Miss Goering reflects, “and now I just reside in my house and try not to be too unhappy.”

She has not entirely abandoned her childhood spirituality. She speaks of seeking “salvation.” The only way to achieve this, she decides, is to live tawdrily, in a tawdry place. This she manages by sleeping with men she encounters in the most sordid bars in the grimmest towns she can find.

Miss Goering’s adventures alternate with those of an acquaintance, Frieda Copperfield, who has married well but is no less restless. She wants something more than comfort and order—but what? On a trip to Panama City, while her husband goes sightseeing, she finds her own salvation in a passionate, chaotic relationship with a local teenage prostitute named Pacifica. Soon she has ditched Mr. Copperfield altogether. “I am completely satisfied and contented,” she says near the end of the novel, after she has brought Pacifica back to New York and introduced her to Miss Goering. “I can’t live without her for a minute. I’d go completely to pieces.”

“But you have gone to pieces,” Miss Goering points out.

Mrs. Copperfield’s reply serves as the clearest expression of Bowles’ theme:

“True enough,” said Mrs. Copperfield, bringing her fist down on the table and looking very mean. “I have gone to pieces, which is a thing I’ve wanted to do for years. I know I am as guilty as I can be, but I have my happiness, which I guard like a wolf, and I have authority now and a certain amount of daring, which, if you remember correctly, I never had before.”

“Going to pieces” is another way of saying that she refuses to live cautiously, and no longer cares if her actions should outrage her husband or her friends. Mrs. Copperfield’s fierceness is unmistakable—the fist coming down on the table, the mean look, the wolfish pride—and triumphant. Going to pieces can be liberating, she realizes, perhaps even more liberating than finding work on an assembly line.

But it’s not just Bowles’ heroines that are going to pieces. The men are equally adrift. While Mrs. Copperfield consorts with Pacifica, Mr. Copperfield ventures deeper and deeper into the Panamanian jungle, in search of isolation and wildness. Arnold, a man who moves in with Miss Goering, stops going to work, eats gluttonously, and sleeps during the day, growing fat and feral. Arnold’s father, who initially appears a stern, old-fashioned sort of man, abandons his wife, hits on Miss Goering and her friends, and delivers poetic odes to the night sky.

There is an affinity between Bowles’s theme and her language that one rarely encounters in fiction. With their odd involutions and surprising turns, her sentences themselves often seem to be going to pieces. But they always resolve triumphantly. Take, as a single example, the following sentence, which describes a woman on the verge of losing her mind. The act of reading it can make you feel like you are losing your own mind:

The world and the people in it had suddenly slipped beyond her comprehension and she felt in great danger of losing the whole world once and for all—a feeling that is difficult to explain.

But that’s Bowles—explaining things that are difficult to explain, while suggesting that the true things in life are unexplainable.

Other notable novels published in 1943:

Double Indemnity by James M. CainLaura by Vera CasparyThe Lady in the Lake by Raymond ChandlerJohnny Tremain by Esther ForbesGideon Planish by Sinclair LewisThe Fountainhead by Ayn RandThe Human Comedy by William SaroyanA Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty SmithThe Big Rock Candy Mountain by Wallace StegnerAt Heaven’s Gate by Robert Penn WarrenBlack Angel by Cornell Woolrich

Pulitzer Prize:

Dragon’s Teeth by Upton Sinclair

Bestselling novel of the year:

The Robe by Lloyd C. Douglas

About this series:

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2013. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers.

Previous Selections:

1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon 1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson1922—Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis 1932—Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell 1942—A Time to Be Born by Dawn Powell 1952—Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison 1962—One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey 1972—The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin1982—The Mosquito Coast by Paul Theroux1992—Clockers by Richard Price2002—Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides2012—Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain1903—The Call of the Wild by Jack London1913—O Pioneers! By Willa Cather1923—Black Oxen by Gertrude Atherton1933—Miss Lonelyhearts by Nathanael West