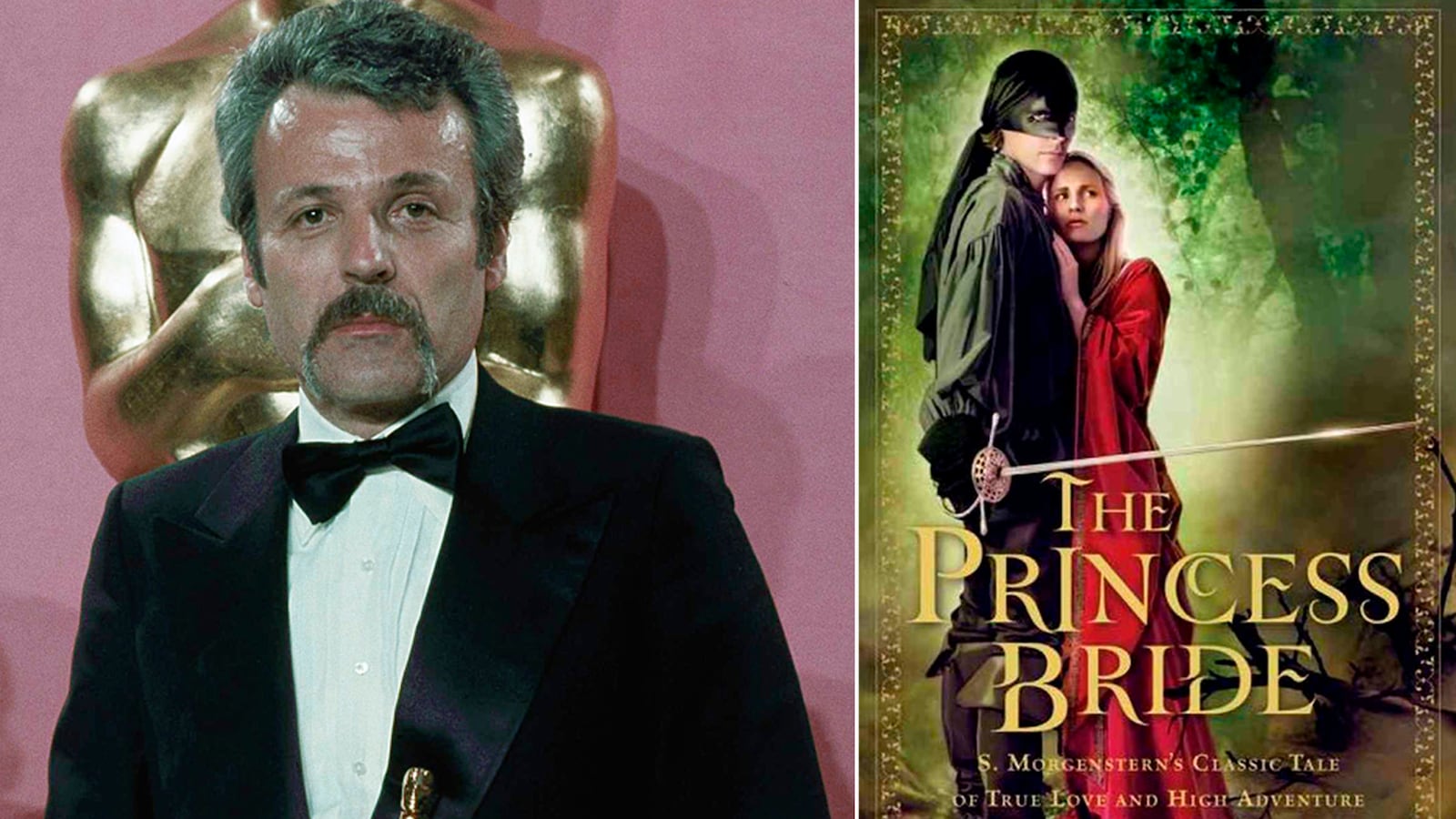

In 1973—“the year of infamy”—the last American bombs were dropped on Cambodia, OPEC issued an oil embargo, the stock market crashed, and Woodward and Bernstein revealed that there was more to the Watergate break-in than had first appeared. Even by American standards, it was a moment of extravagant uneasiness, disillusionment, and mania. In the midst of this maelstrom came a strange and determinedly anachronistic new novel by William Goldman. It told the fairy-tale story of a Princess named Buttercup, her abduction by an evil prince and a six-fingered count, and her rescue by a soft-hearted giant, a vengeance-mad swordsman, and a debonair masked hero named Westley. It is difficult to think of a novel that bears less connection to its time than The Princess Bride. Which is exactly what made The Princess Bride so timely.

It’s possible that a suspicious reader might discern certain Nixonian qualities in Humperdinck, Goldman’s vain, conspiratorial, power-hungry prince, or see in Count Rugen, the prince’s diabolical, merciless, hypocritical hatchet man, a medieval Robert Haldeman. But Goldman isn’t interested in satire; in fact it is one of the novel’s central motifs that satire is a bloodless, empty exercise, lost on all but the most pretentious, scholarly readers. There is plenty of room for observations of this kind, for “The Princess Bride” is a novel within a novel. In a thirty-page, first-person introduction, Goldman explains that it was written by S. Morgenstern, the legendary Florinese writer (Florin being a country “set between where Sweden and Germany would eventually settle”), and read to Goldman as a child by his father, a Florinese immigrant. When Goldman revisits the novel as an adult, he realizes that his father skipped many hundreds of pages in his reading, much of it historical detail, backstory, and long, tediously satirical passages about Florinese customs: fifty-six pages on a queen’s wardrobe, for instance, or seventy-two pages about the royal training of a princess. “For Morgenstern,” writes Goldman, “the real narrative was not Buttercup and the remarkable things she endures, but, rather, the history of the monarchy and other such stuff.”

Goldman’s Princess Bride is therefore an abridgement, with all of the “other such stuff” having been removed (but summarized in playful asides). What we are left with is “the ‘good parts’ version”—a rare understatement in a novel filled with dastardly deeds and thrilling feats of derring-do. Goldman is one of the century’s hall-of-fame storytellers, and in The Princess Bride he moves from strength to strength, each chapter a new adventure more surprising and delicious than the last: the passionate, unspoken love affair between Buttercup and her Farm Boy, Inigo Montoya’s twenty-year quest to avenge the death of his father, and Westley’s attempts to survive torments like the Fire Swamp, the Zoo of Death, and an infernal torture device known simply as the Machine, while trying to rescue Buttercup from Humperdinck. It is one of the basic rules of storytelling that your characters must overcome difficult situations, but Goldman takes this formula to impossible extremes. At one point, for instance, Westley must storm a heavily fortified castle defended by one hundred men, with only a bumbling giant and an alcoholic swordsman to assist him. Further complicating matters is the fact that, one chapter earlier, Westley died.

The swashbuckling adventure is interrupted by an irreverent running commentary about S. Morgenstern’s narrative tics and preoccupations, an approach that allows Goldman to exploit the conventions of storytelling while subverting them at the same time. It is a kind of literary magic trick, the equivalent of the Penn and Teller bits in which Penn discloses how he pulled off an illusion—a disclosure (which is usually false) that manages to make the illusion even more astonishing in retrospect. We feverishly turn the pages of The Princess Bride not to find out whether Westley will come back from the dead—he will, three times in fact—but to see how Goldman will pull off his next Houdini escape. We read also for his playful, light touch, the charming vulnerability of his characters, and the deep satisfactions of a nimbly executed revenge plot. The novel is simultaneously a celebration and an exemplar of the joys of storytelling.

Like all fairy tales, The Princess Bride offers a moral:

…that’s what I think this book’s about. All those Columbia experts can spiel all they want about the delicious satire; they’re crazy. This book says “life isn’t fair” and I’m telling you, one and all, you better believe it…The wrong people die, some of them, and the reason is this: life is not fair.

It was a moral that happened to be particularly well-suited to a year when, as the Watergate scandal continued to unfold, an American public begun to learn exactly how unfair life really was. It is an important theme to Goldman, one he would soon revisit in his screenplay for All the President’s Men, a tale of palace intrigue worthy of S. Morgenstern. Thrilling stories, whether timely or not, are timeless.

Other notable novels published in 1973:

Rubyfruit Jungle by Rita Mae Brown Great Jones Street by Don DeLillo Nickel Mountain by John Gardner Fear of Flying by Erica Jong Child of God by Cormac McCarthy 92 in the Shade by Thomas McGuane Sula by Toni Morrison Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon The Great American Novel by Philip Roth Burr by Gore Vidal Breakfast of Champions by Kurt Vonnegut

Pulitzer Prize:

The Optimist’s Daughter by Eudora Welty

National Book Award:

Chimera by John Barth

Bestselling novel of the year:

Jonathan Livingston Seagull by Richard Bach

About this series:

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2013. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers.

Previous Selections:

1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson1922—Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis1932—Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell1942—A Time to Be Born by Dawn Powell1952—Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison1962—One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey1972—The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin1982—The Mosquito Coast by Paul Theroux1992—Clockers by Richard Price2002—Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides2012—Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain1903—The Call of the Wild by Jack London1913—O Pioneers! By Willa Cather1923—Black Oxen by Gertrude Atherton1933—Miss Lonelyhearts by Nathanael West1943—Two Serious Ladies by Jane Bowles1953—Junky by William S. Burroughs1963—The Group by Mary McCarthy