The best-selling book in the United States for much of 1984 was 1984. In the first weeks of January, George Orwell’s novel sold more than 50,000 copies every single day. It was the subject of think pieces, art projects, and academic conferences with names like “Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four: Fact or Fiction?” On January 1 the Korean visual artist Nam June Paik debuted “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell,” a rebuke to Orwell’s grim view of television as a form of thought control; Paik wanted to show “the positive side of the medium” by broadcasting around the world a variety show featuring John Cage, Salvador Dali, Allen Ginsberg, Merce Cunningham, and Peter Gabriel. “We think video can be comparable to the best of the printed media,” Paik said, “and can be just as influential.” This was a radical idea in 1984, that television could be just as influential as print.

The Soviet political press identified counterparts of Newspeak, the Thought Police, and the Ministry of Truth in modern America; Big Brother, needless to say, was Ronald Reagan. Vice President George Bush, meanwhile, railed against Big Brother’s presence in Cuba. The most famous invocation of Orwell occurred during the Super Bowl, when Apple introduced its new “MacIntosh” computer with its “1984” spot, directed by Ridley Scott, in which a sledgehammer, whirling end-over-end, smashes through a giant television screen, awakening the narcotized masses. That ad was inspired by an abandoned print campaign that made Apple’s message explicit. “True enough,” read the copy, “there are monster computers lurking in big business and big government that know everything from what motels you’ve stayed at to how much money you have in the bank. But at Apple we’re trying to balance the scales by giving individuals the kind of computer power once reserved for corporations.”

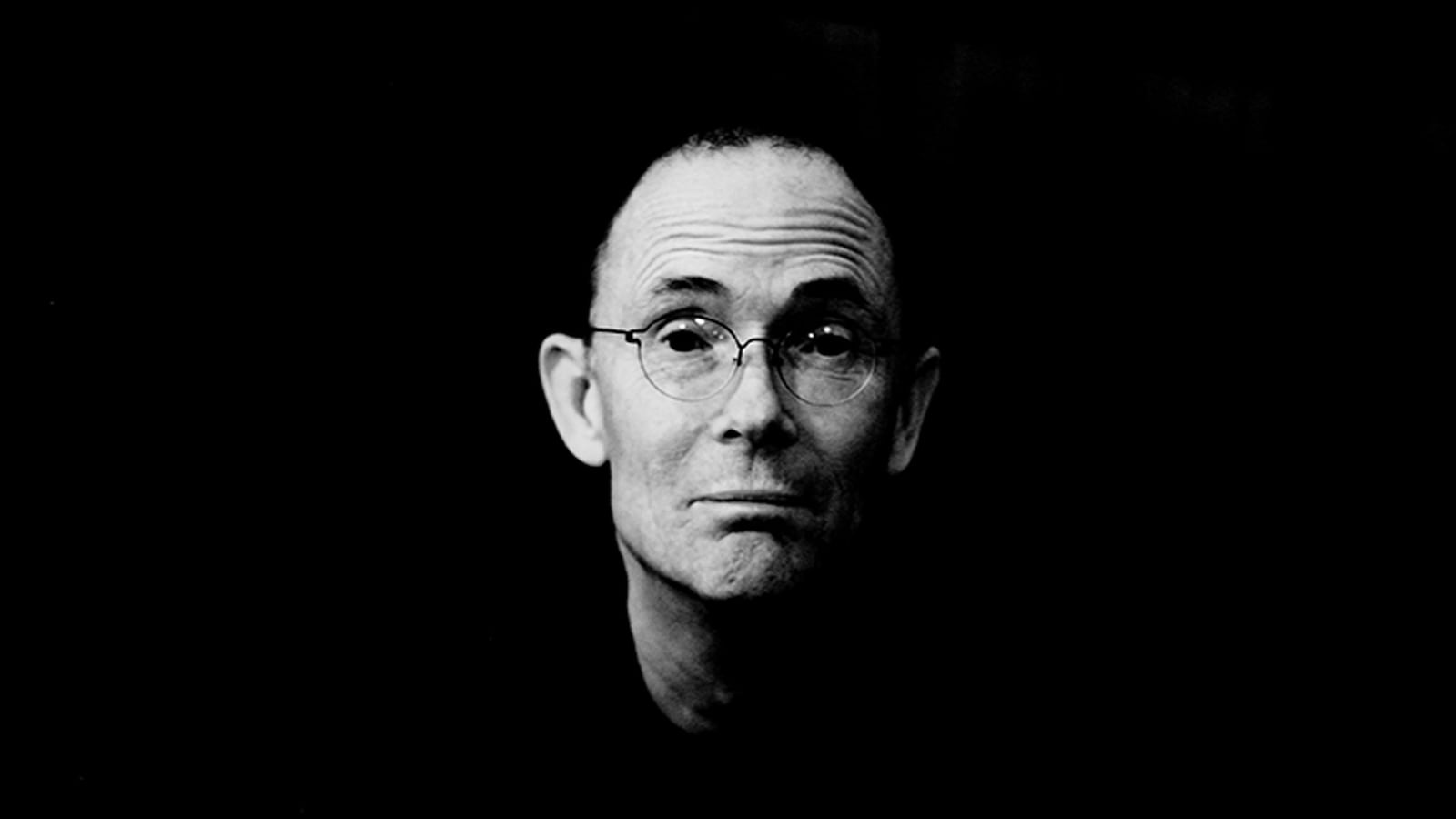

True enough indeed. 1984 might not have been 1984, but the paranoia was warranted. This might be why William Gibson’s Neuromancer, published the same year, achieved such enormous success, winning the Hugo, the Nebula, and Philip K. Dick Awards and going on to sell more than six million copies. Gibson got the idea for the novel after seeing a bus stop poster for Apple. It showed a businessman holding a small computer in his hand. “Everyone is going to have one of these, I thought,” Gibson told his Paris Review interviewer, “and everyone is going to want to live inside them.” He began to imagine what this future would be like, when everybody lived inside a virtual universe. He named the universe “cyberspace.”

Neuromancer is more exciting to read about than it is to read, stronger as a work of prophecy and satire than the futuristic crime caper it professes to be. Notionally it follows the psychedelic adventures of one Henry Dorsett Case, a 24-year-old hacker or, as Gibson puts it, “console cowboy.” He is caught stealing by his former employer, who poisons his nervous system with a mycotoxin. Case’s life is saved, and his hacking powers restored, by a femme fatale named Molly Millions and her boss, a mysterious former military man named Armitage. In exchange for his treatment, Case is forced to do Armitage’s bidding. His first job is to break into Sense/Net, a corporation that possesses the uploaded consciousness of Case’s dead mentor; later they discover that Armitage, who turns out to be a disgraced former army general named Corto, is working for Wintermute, an artificial intelligence, housed in a computer mainframe in Switzerland, and created by inventors who live in cryonic preservation…

Neuromancer is willfully abstruse, written in coded, inscrutable prose: “In the nonspace of the matrix, the interior of a given data construct possessed unlimited subjective dimension…”

“Your glasses gimme the read they always have, low-temp isotropic carbons. Better biocompatibility with pyrolitics, but that’s your business, right?”

“So it looks like they link via Straylight, the T-A home base, down the end of the spindle, and we’re supposed to cut our way in with the Chinese icebreaker.”

Yet there are glimpses of surpassingly eerie dystopian beauty. The sky, variously, is “poisoned silver,” “the recorded blue of a Cannes sky,” or, in the novel’s first sentence, “the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.” Tokyo Bay is “a black expanse where gulls wheeled above drifting shoals of white Styrofoam.” A Japanese red-light district is “like a deranged experiment in social Darwinism, designed by a bored researcher who kept one thumb permanently on the fast-forward button.” An artificial intelligence, taking over a human brain, glides “into the man’s flat gray field of consciousness like a water spider crossing the face of some stagnant pool.” The best way to read the novel is to follow Case’s example and “jack in” to its matrix, allowing the images to pass through as under the spell of a narcotic, while ignoring the noise of the constant stream of data.

Thirty years after the novel’s publication, it’s difficult to tell whether Gibson foresaw the future or whether the future, designed by technologists who idolized Gibson’s novels, self-consciously imitated his novel. Neuromancer gave us not only “cyberspace,” “a consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions,” but also “the net,” “the matrix,” and “dub music,” a “sensuous mosaic cooked from vast libraries of digitalized pop.” The cities along the Eastern seaboard from Boston and Atlanta have yet to merge into a single megalopolitan “Sprawl,” but it is only a matter of time. Starbucks has become Beautiful Girl, “a franchised coffee shop” seen on nearly every street corner. Microsoft was founded before the novel’s publication, but Gibson’s “microsofts,” small computer chips that insert directly into the brain, may well represent the company’s ultimate goal.

There was consensus, in 1984, that the world hadn’t become 1984 just yet. But there was also anxiety that Orwell’s world was well on its way to becoming reality. Only when it did, it wouldn’t look like Airstrip One; it would be far more chaotic, neon, hallucinatory, and violent. It would look like Neuromancer.

Other notable novels published in 1984: The House on Mango Street by Sandra CisnerosLove Medicine by Louise ErdrichMachine Dreams by Jayne Anne PhillipsThe Witches of Eastwick by John UpdikeLincoln by Gore Vidal

Pulitzer Prize:Ironweed by William Kennedy

National Book Award:Victory Over Japan by Ellen Gilchrist

Bestselling novel of the year:The Talisman by Stephen King and Peter Straub

About this series:

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2013. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers.—Nathaniel Rich

Previous Selections

1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson1922—Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis1932—Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell1942—A Time to Be Born by Dawn Powell1952—Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison1962—One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey1972—The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin1982—The Mosquito Coast by Paul Theroux1992—Clockers by Richard Price2002—Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides2012—Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain1903—The Call of the Wild by Jack London1913—O Pioneers! By Willa Cather1923—Black Oxen by Gertrude Atherton1933—Miss Lonelyhearts by Nathanael West1943—Two Serious Ladies by Jane Bowles1953—Junky by William S. Burroughs1963—The Group by Mary McCarthy1973—The Princess Bride by William Goldman1983—Meditations in Green by Stephen Wright1993—The Road to Wellville by T.C. Boyle2003—The Known World by Edward P. Jones2013—Equilateral by Ken Kalfus1904—The Golden Bowl by Henry James1914—Penrod by Booth Tarkington1924—So Big by Edna Ferber1934—Appointment in Samarra by John O’Hara1944—Strange Fruit by Lillian Smith1954—The Bad Seed by William March1964—Herzog by Saul Bellow1974—Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig