To appreciate how radical was If He Hollers Let Him Go, you need only compare it to Strange Fruit, Lillian Smith’s bestselling race novel of one year earlier. A gloomy parable about miscegenation in a small Southern town, Strange Fruit is closer to a manifesto than a flesh-and-blood novel. Straining to win the sympathy of her white readers, Smith stacks the deck: the racist townspeople are cartoonishly ignorant and crude, while the black heroine is unerringly decorous, noble, and so light-skinned that she is mistaken for white. Smith, born to a prosperous white Southern family, was a social critic and activist. Disturbed by the condition of race relations in America, she sought to change public opinion through fiction.

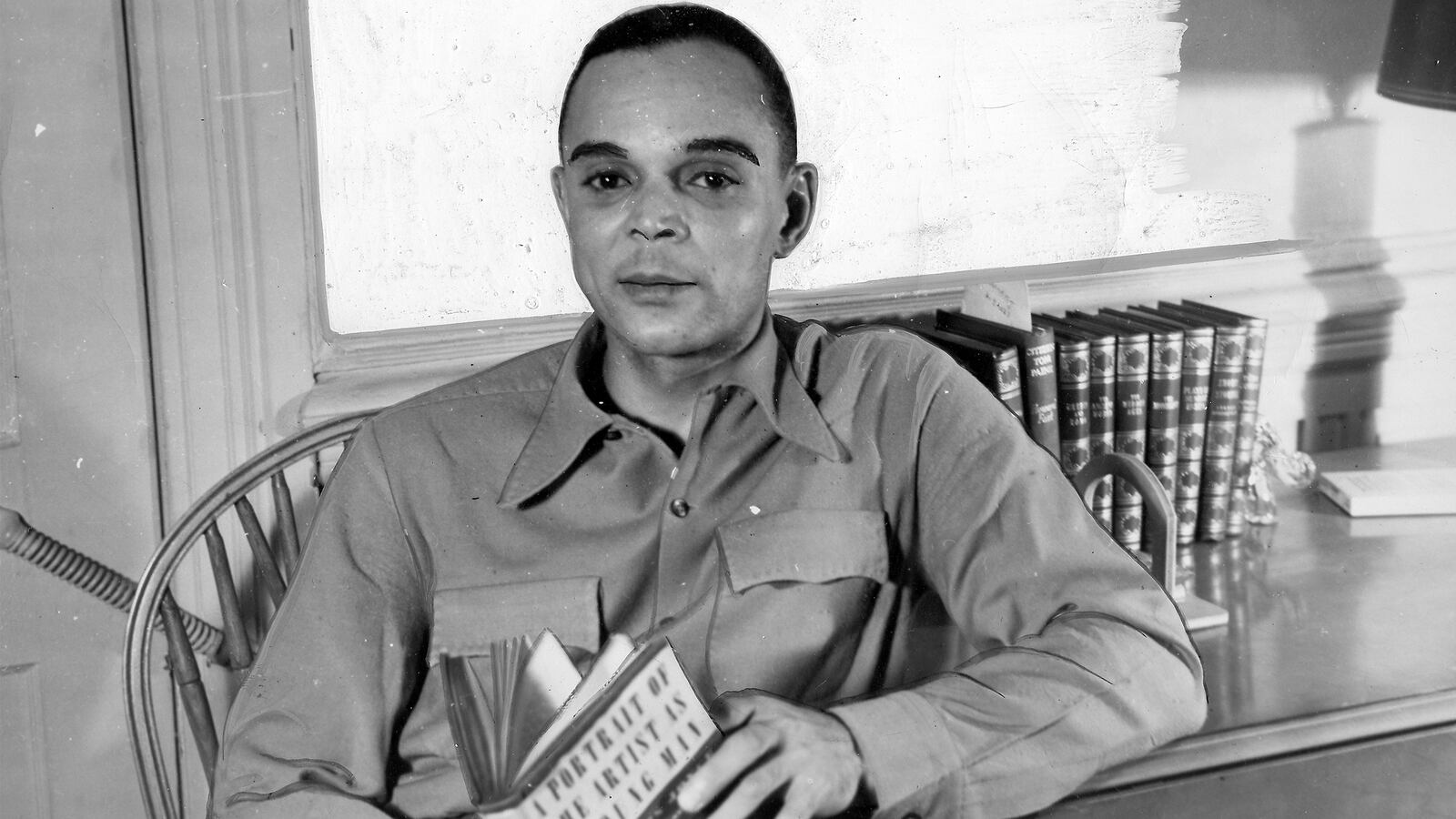

Chester Himes had no such hang-ups. He was a black shipyard worker who even as he built ships for his own country’s military had to endure the outrages of racism, as well as its myriad daily inconveniences, slights, and indignities. He did not have the luxury of melancholy reflection or even activism. He was only furious. His rage disfigured him, and this disfiguration is the subject of his debut novel. If Strange Fruit was a bombshell, If He Hollers Let Him Go was a knife in the ribs.

The novel takes place during four days in the life of Robert Jones, a foreman in the Los Angeles shipyard. Jones is tormented by every white person he encounters, including his boss, various police officers, and a female coworker who falsely accuses him of rape. But even in the novel’s opening pages he is fed up. Jones dates his anger to the beginning of World War II, when he moved west from Cleveland for work. “When I came out to Los Angeles in the fall of ’41, I felt fine about everything. Taller than the average man, six feet two, broad-shouldered, and conceited, I hadn’t a worry … Race was a handicap, sure, I’d reasoned. But hell, I didn’t have to marry it.”

He has been subjected to casual racism and been refused service in both Ohio and California, but that isn’t what set him off. What bothered him—what horrified him—was the internment of the Japanese.

“It was taking a man up by the roots and locking him up without a chance. Without a trial. Without a charge. Without even giving him a chance to say one word.” America is at war and not, he realizes, only against the Axis Powers. There is also an internal war brewing. “I was the same color as the Japanese and I couldn’t tell the difference,” says Jones. If they were going to lock away the Japanese, what would stop them from locking him away, too?

The answer, we soon learn, is absolutely nothing. He cannot drive 10 blocks in Los Angeles without being pulled over by a policeman and questioned. He cannot park on the street without arousing suspicion. When a white woman baselessly accuses him of threatening her, he loses his foreman job; the demotion costs him his war deferment.

“I don’t like to be pushed around all the time,” he says. “A guy wants to feel he can control at least some of his life … I don’t want to always be thinking about my race either. I get awful goddamn tired of it. But the white people make me think about it in every way.”

When a white liberal activist praises Strange Fruit, Jones flatly dismisses the novel as a romantic fantasy, flattering to its white readers and condescending to its black heroine. In the real America of 1945, he concludes, there are only three possibilities open to young black men: jail, the army, or death.

Against his will, Jones finds himself becoming the fulfillment of white America’s nightmare. Driven to the brink of insanity by the abuse he suffers almost constantly, he fantasizes about revenge, beginning with a bigoted coworker who he has sparred with. “I wanted him to feel as scared and powerless and unprotected as I felt every goddamned morning I woke up,” says Jones. He vows to murder the man in cold blood, in front of his family if possible. Then he gets a better idea. He’ll get even with the white woman who has gotten him demoted—by raping her. Even Lillian Smith would have blanched.

If He Hollers Let Him Go occupies a peculiar position in Himes’s bibliography. In 1956, after a series of violent, ruminative novels about race—and after moving to France—he was solicited by Marcel Duhamel, the editor of Série Noire. Duhamel published American crime novels for a French audience that had become obsessed with the form (“Serie Noire” was an inspiration for the term “film noir”) and he offered Himes a large advance to write one. That novel, later published in America as A Rage in Harlem, was the first of a series of detective novels that won Himes acclaim and fortune. But none of them possessed the sheer dark rage of If He Hollers Let Him Go. Even by the conventions of noir literature, it is Himes’s debut novel that was, inadvertently, truest to the form.

Bob Jones is the quintessential noir hero: an innocent man, down on his luck, victimized by a society hostile to those on the bottom. He makes a single mistake—talking back to a white woman who slanders him—and when he tries to rectify it, he only compounds the problem, leading to yet another mistake, and so on, his life spiraling down the gutter. This is the classic noir scenario, familiar today from hundreds of novels and films produced during the late ’40s and ’50s. But the noir form, with its familiar plots and conventions, was in its infancy in 1945, when Himes published If He Hollers Let Him Go. Himes was not trying to hew to a specific formula or tone, as he did in the later Harlem novels. He was only writing what he knew.

Other notable novels published in 1945:

Focus by Arthur Miller

Pulitzer Prize: A Bell for Adano by John Hersey

Bestselling novel of the year: Forever Amber by Kathleen Winsor

About this series:

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2014. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers. — Nathaniel Rich

Previous Selections

1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon 1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson 1922—Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis 1932—Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell 1942—A Time to Be Born by Dawn Powell 1952—Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison 1962—One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey 1972—The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin 1982—The Mosquito Coast by Paul Theroux 1992—Clockers by Richard Price 2002—Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2012—Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain 1903—The Call of the Wild by Jack London 1913—O Pioneers! By Willa Cather 1923—Black Oxen by Gertrude Atherton 1933—Miss Lonelyhearts by Nathanael West 1943—Two Serious Ladies by Jane Bowles 1953—Junky by William S. Burroughs 1963—The Group by Mary McCarthy 1973—The Princess Bride by William Goldman 1983—Meditations in Green by Stephen Wright 1993—The Road to Wellville by T.C. Boyle 2003—The Known World by Edward P. Jones 2013—Equilateral by Ken Kalfus 1904—The Golden Bowl by Henry James 1914—Penrod by Booth Tarkington 1924—So Big by Edna Ferber 1934—Appointment in Samarra by John O’Hara 1944—Strange Fruit by Lillian Smith 1954—The Bad Seed by William March 1964—Herzog by Saul Bellow1974—Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig1984—Neuromancer by William Gibson1994—The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields2004—The Plot Against America by Philip Roth2014—The Book of Unknown Americans by Cristina Henríquez1905—The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton1915—Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman1925—Gentlemen Prefer Blondes by Anita Loos1935—Pylon by William Faulkner