It became obvious, around the turn of last century, that something was very wrong with America’s farmers. Many of them—much too many—had lost their minds. “An alarming amount of insanity occurs in the new prairie States among farmers and their wives,” observed E.V. Smalley, the editor of Northwest Illustrated Monthly Magazine, in 1893. The cause, Smalley believed, was loneliness. The Northern European immigrants who came to settle Nebraska and the Dakotas were accustomed to living in small farming villages, among people their family had known for generations. Now, marooned on the Great Plains, separated from their neighbors by vast distances, language barriers, and extreme weather, they lived in almost total isolation. “Is it any wonder,” asked Smalley, that so many settlers “lose their mental balance?”

In The Americans, the historian Daniel Boorstin traced the madness of the farmers to the Homestead Act of 1862. The legislation, signed by Abraham Lincoln, decreed that a settler had to live on his acreage for five years in order to perfect his title. That meant towns, or even villages, were almost inconceivable. As the size of a settler’s plot increased, so did the distance he would have to travel to visit his neighbor. Since greed tended to prevail over comity, the Great Plains bred depressives and sociopaths. By 1908 the problem had become so dire that Theodore Roosevelt created a Commission on Country Life to improve social conditions for farmers and eliminate “the disadvantages which are due to the isolation of the family farm.” Roosevelt’s commission ended in failure. It was too late to reconfigure the organization of the land, and the spirit of isolation—or self-reliance, to give it a grander name—had become ingrained in the local character. American farmers were doomed to insanity.

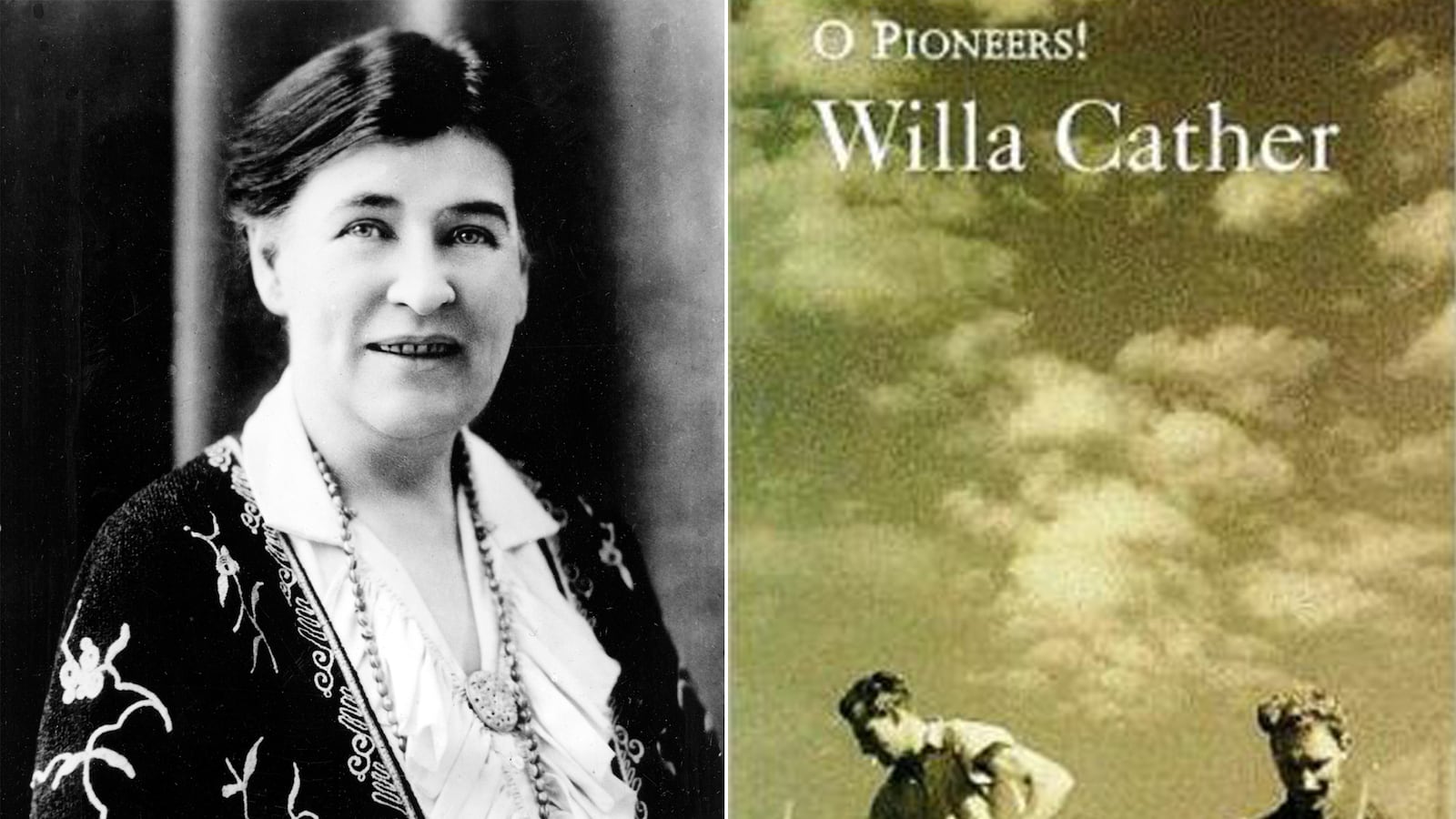

It is in this context that one should read Willa Cather’s O Pioneers!, which follows the lives of several mentally unstable Nebraskan homesteaders between 1883 and 1900. In the novel’s opening section, this “dark country” feels like “the end of the earth”; the expanse is so immense that it seems “to overwhelm the little beginnings of human society that struggled in its somber wastes.” To some extent, Cather is speaking literally: the settlers’ houses are built out of the sod itself, and so tiny, that they are invisible to the eye sweeping across the plain—“you did not see them until you came directly upon them.” But the landscape’s vast dreariness also wreaks psychological damage. The settlers felt themselves “too weak to make any mark here, that the land wanted to be let alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar, savage kind of beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness.” Even wild flowers, a symbol for youthful spirit if ever there was one, are snuffed out by the brutality of the plains. They’ve all disappeared, except “a few of the very toughest and hardiest,” which settle “only in the bottom of the draws and gullies.”

One of Cather’s wildest flowers is Marie Tovesky, a young Bohemian girl who is too pretty for her own good. After her 18th birthday she elopes with a handsome, tall, oafish farmer named Frank Shabata, who promptly makes her miserable with his jealousy. He also drives himself crazy, because there are so few men for him to suspect of seducing his wife; the only other boy with whom Marie comes into contact is the teenage farmhand. Secretly, however, Marie pines for Emil Bergson, a dreamer and intellect who seems ill-suited to life on a farm. The star-crossed lovers are separated by acres upon acres.

In a second story, Emil’s prudent, wise older sister Alexandra falls in love, long past her prime, with another dreamer, named Carl Linstrum. He has left the plains to pursue life as an artist in New York City, only to return a failure. He woos Alexandra, but he is rebuffed by her two older brothers, who distrust any man who has seen the world beyond Nebraska.

Despite their differences, all of Cather’s characters have one thing in common: they are desperately, excruciatingly lonely. “There are only two or three human stories,” says Carl, while walking past a graveyard, “and they go on repeating themselves as fiercely as if they had never happened before.” Carl never makes explicit what these three stories are, but it is safe to say that at least one of them involves the terrors of isolation.

For a century now, critics have tried to align Cather’s fiction with one ideology or another, and all have failed—this failure is even the subject of a book by Joan Acocella, Willa Cather and the Politics of Criticism. In O Pioneers!, as elsewhere, Cather works diligently to resist solutions to her characters’ dilemmas; this is her great talent, and the source of her courage as a writer. Carl is repaid for his worldliness with failure and ignominy. Marie and Emil, the tragically thwarted lovers, are penalized with death. Determined, reasonable Alexandra must endure decades of sorrow. Frank goes insane and slaughters his wife. And as cruel as the homesteading existence can be, city life is worse. When Alexandra speaks ruefully of her anonymous life on the plains, where she had no personality “apart from the soil,” Carl chastens her:

“Here you are an individual, you have a background of your own, you would be missed. But off there in the cities there are thousands of rolling stones like me. We are all alike; we have no ties, we know nobody, we own nothing ... We sit in restaurants and concert halls and look about at the hundreds of our own kind and shudder.”

Loneliness, Cather suggests, knows no geographical bounds. People are isolated wherever they find themselves, whether in the middle of a vast rural expanse or amid an urban crowd. Prairie madness is the common condition, one of the human stories that goes on repeating itself, “like the larks in this country, that have been singing the same five notes over for thousands of years.”

Other novels published in 1913:

Roast Beef, Medium by Edna FerberVirginia by Ellen GlasgowJohn Barleycorn by Jack LondonThe Valley of the Moon by Jack LondonPollyanna by Eleanor H. PorterMy Little Sister by Elizabeth RobinsThe Custom of the Country by Edith Wharton

Bestselling novel of the year:

The Inside of the Cup by Winston Churchill

About this series:

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2013. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers.

Previous Selections:

1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon 1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson1922—Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis 1932—Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell 1942—A Time to Be Born by Dawn Powell 1952—Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison 1962—One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey 1972—The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin1982—The Mosquito Coast by Paul Theroux1992—Clockers by Richard Price2002—Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides2012—Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain1903—The Call of the Wild by Jack London