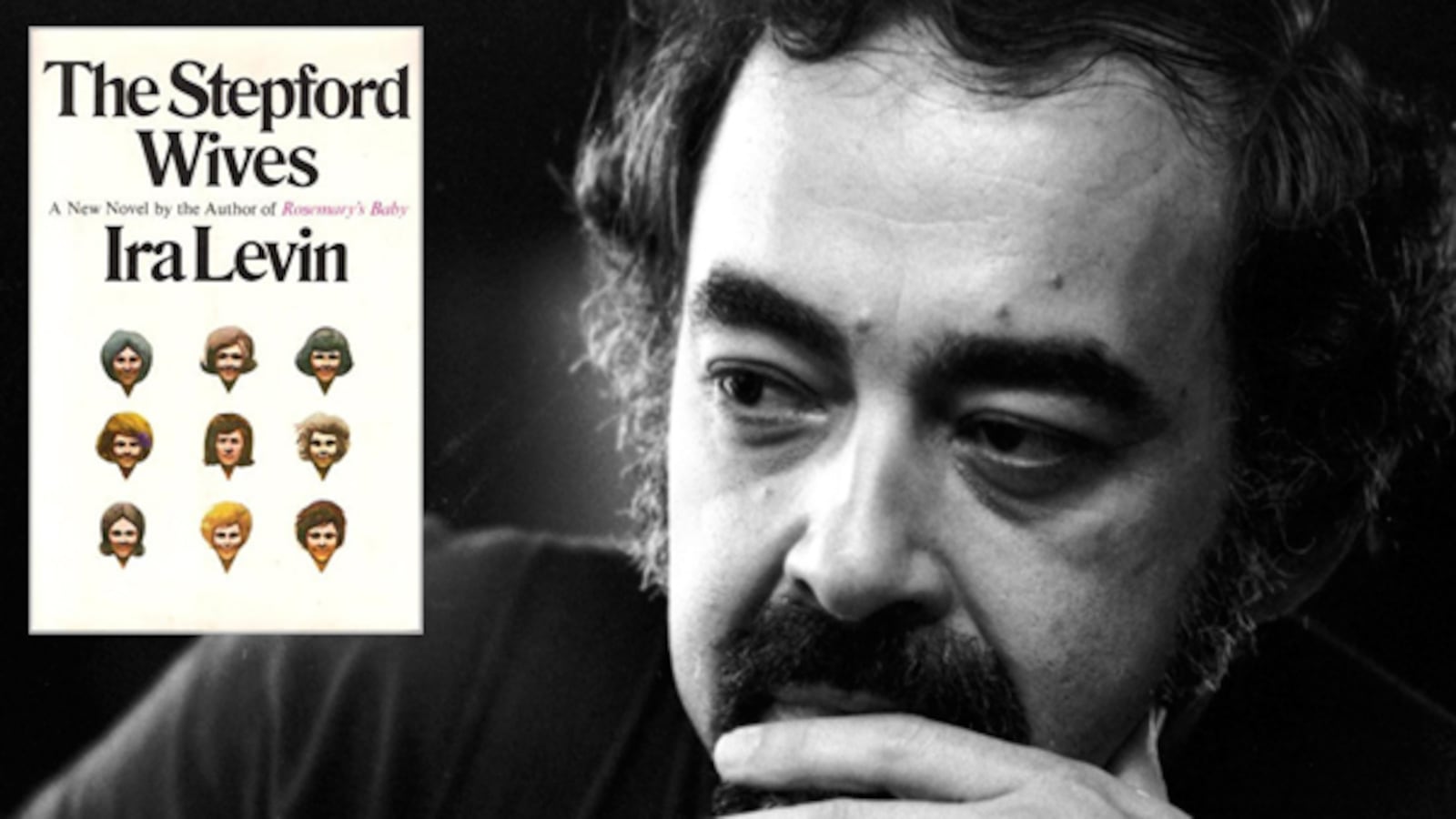

The original hardcover jacket calls The Stepford Wives “one of those rare novels whose very title may well become part of our vocabulary”—which is one of those rare examples of a jacket copy prophecy come true. Forty years after the novel’s publication, the adjective “Stepford” has not only entered the lexicon (“blandly conformist and submissive” according to the Collins English Dictionary), but is trending upward this political season. The word is invoked almost daily by pundits to describe not only Mitt Romney, but his wife Ann and their entire loving brood.

Yet those who call Mitt a “Stepford Husband” do so confusedly. They mean to say that he is bland and conformist, but in the context of Ira Levin’s novel, a Stepford husband is an entirely different creature from a Stepford wife: he is conniving, angry, murderous. And no Stepford husband would ever tolerate a wife with as consuming a personal passion as dressage.

The Stepford Wives has one of the most enduring premises of 20th-century American fiction. Joanna and Walter Eberhart move with their two children to the suburbs in the hope of a more comfortable life. They abandon New York—“the filthy, crowded, crime-ridden, but so-alive city”—for two-point-two acres in Stepford, a “postcard pretty” town with white frame colonial shopfronts and indistinguishable streets with names like Harvest Lane and Short Ridge Road. If you squint you might confuse Stepford with John Updike’s Eastwick, Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Hill Estates, or John Cheever’s Shady Hill. The main difference is that the homes of Stepford are kept unusually clean by unusually beautiful, and unusually buxom, wives. These women, Joanna observes, resemble “actresses in commercials, pleased with detergents and floor wax, with cleansers, shampoos, and deodorants. Pretty actresses, big in the bosom but small in the talent, playing suburban housewives unconvincingly, too nicey-nice to be real.”

As Joanna discovers too late, the Stepford Wives are not real at all. They are androids—the brainchild of a neighbor who moved to Stepford from Anaheim, where he designed animatronics at Disneyland. (The Stepford Wives is one of the earliest, and canniest satires of the Disneyfication of American culture.) The men of Stepford have conspired to upgrade their spouses, replacing them with more attractive, subservient, and sexually acquiescent replicas.

What’s often forgotten by those who casually invoke the name of Levin’s fictional suburb is that his subject is, quite explicitly, the feminist movement. In the novel’s opening scene, when Joanna is asked by a woman from the Stepford Chronicle to list her hobbies and special interests, she replies, “I’m very interested in the Women’s Liberation movement. Very much so in that. And so is my husband.”

“He is?” says the astonished reporter.

Joanna learns that strange things only began to happen in Stepford after Betty Friedan herself came to speak to the Women’s Club half a dozen years earlier, following the publication of The Feminine Mystique. Joanna finds an article in a yellowed copy of the Stepford Chronicle about the speech: “Over fifty women applauded Mrs. Friedan as she cited the inequities and frustrations besetting the modern-day housewife.”

One of the more subversive aspects of Levin’s premise is that it takes only the mildest acts of rebellion to induce the men of Stepford to slaughter their wives. Friedan’s visit, after all, did not bring about any major rebellion. The women of Stepford don’t burn their bras or write manifestos. They merely neglect to wear lipstick, except at social functions; become indifferent to housework; and pursue private hobbies, such as photography, or writing books for children. But for the men of Stepford, these are crimes punishable by death. Even those most sensitive to discrimination—such as the town’s token Jewish and black patriarchs—are easily persuaded to replace their wives with robots.

Their conspiracy only succeeds because women like Joanna, as soon as they begin to question their domestic roles, feel guilty for doing so. Even as evidence mounts, she distrusts her own suspicions, and finds herself taking her husband’s side in their arguments. She agrees that, yes, perhaps she should be more conscientious with her housework. And maybe it wouldn’t hurt to look in a mirror once in a while. She wonders whether she is delusional—whether she’s the problem, not the other wives. Her sense of guilt is exacerbated by the fact that the children of Stepford, though not clever enough to understand what’s going on, clearly prefer their new mothers, who are constantly baking chocolate-chip cookies, to their old ones.

The Stepford Husbands triumph in the novel, but deep down they know that history will not favor them. In the years following the publication of The Feminine Mystique, Congress passed the Equal Pay Act and granted women the same legal protections given to African Americans in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In 1971 the government revised its affirmative action guidelines to include women, and in 1972, the year The Stepford Wives was published, Congress passed Title IX, an amendment to the Educational Amendments. As President Obama pointed out in a recent speech marking the fortieth anniversary of Title IX, more women now graduate college than men by a factor of 25 percent.

In 2012 the fantasy of a Stepford Wife seems quaintly anachronistic, a type better suited to the Fifties than the Seventies, let alone the second decade of the 21st century. But Levin’s portrait of the Stepford Husbands is still as vivid, and familiar, as ever: white suburban men, seething with rage at perceived slights, rendered impotent by the tidal changes they see transforming American society. Today’s Stepford Husbands hope that Mitt Romney, deep down, is not an android at all. They hope that he is one of them.

Other notable novels published in 1972:

Chimera by John Barth The Terminal Man by Michael Crichton End Zone by Don DeLillo Geronimo Rex by Barry Hannah My Name is Asher Lev by Chaim Potok Mumbo Jumbo by Ishmael Reed Freaky Friday by Mary Rodgers Enemies, A Love Story by Isaac Bashevis Singer Augustus by John Williams

Pulitzer Prize:

Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner

National Book Award:

The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor by Flannery O’Connor

Bestselling novel of the year:

Jonathan Livingston Seagull by Richard Bach

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2012. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers.

Previous Selections:

1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon 1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson 1922—Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis1932—Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell1942—A Time to be Born by Dawn Powell1952—Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison1962—One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey