As a comedy, Tobacco Road is a modest failure; as a tragedy, it’s an abject failure. And yet Erskine Caldwell’s novel, 80 years after its publication, remains a giddy, obscene joy. It as indelible as a freak show or car crash. Nobody knew what to make of Caldwell in 1932, and nobody much talks about him now, but his legacy persists. He is a progenitor of what could be called the degenerate school of American fiction. Descendents include writers like William S. Burroughs, Harry Crews, Katherine Dunn, and Barry Gifford. Tobacco Road is crass and deranged and irreducibly American.

The novel received censorious reviews upon publication, but after it was adapted into a play in 1935 and became the longest-running show in the history of Broadway, it went on to sell 10 million copies. It is not surprising that critics were made uneasy by the story of the Lesters (rhymes with festers, molesters, and incesters), a family of cruel, illiterate savages in west-central Georgia. In the early years of the Great Depression, the intellectual preoccupations of the ’20s were swiftly discarded. No longer did artists and critics gripe that America was a mechanized, standardized, puritanical country, governed by Babbitts, prudes, and dimwitted businessmen. As Frederick Lewis Allen writes in Since Yesterday, his history of America in the ’30s, the conversation had turned, with a thud, to economic reform. It was held that “the masses of the citizenry were the people who really mattered, the most fitting subjects for writer and artist, the people on whose behalf reform must be undertaken.” Writers needed to depict conditions as they were for the most unfortunate members of society—that was the only way to bring about social change. It was an innocent time in America, and writers still believed that fiction could bring about change.

The Lesters, at first glance, seem the ideal heroes of a Depression-era novel. They are poor; “dirt poor” is no exaggeration, for their land has been depleted by cotton farming and untilled for seven years. Seventy-five years earlier, grandfather Lester had owned a great tobacco plantation, but the property has long since been sold off to creditors. The Lesters only remain on their small parcel thanks to the pity of its new owner. Their house, which has never been painted, is sagging and rotted and porous. Sections of ceiling fall away every time it rains.

Jeeter Lester, the patriarch, has 12 surviving children. He doesn’t remember most of their names. All but two have left and never returned. Since Lester cannot afford to rent a mule or basic farming supplies, his main income comes from selling his daughters into marriage. He trades Pearl, 12, to a neighbor for some quilts, not quite a gallon of cylinder oil, and $7.

Jeeter lives with his wife, Ada, who suffers from pellagra and spends her days daydreaming about buying a nice dress in which to be buried; his mother, whom nobody talks to, except to tell her “to get out of the way, or to stop eating the bread and meat”; a big stupid son, Dude, 16; and a daughter, Ellie May, 18. The only reason Ellie May hasn’t been married is because she has a gruesome harelip that makes her gums look like “a bleeding, painful wound.” The family is slowly starving to death.

None of these characters would be caught dead in a novel by John Steinbeck, Carson McCullers, or Eudora Welty. The Lesters are poor, but they have no dignity. They behave like wild animals. They steal from each other, beat each other, try to have sex with each other. They are violent, terminally stupid, and slothful to a pathological degree. Jeeter is so lazy that when he trips, he stays on the ground for an hour before bothering to get back up.

The wanton crudeness of the Lesters frustrated Caldwell’s critics. Was the novel a cry for social justice, or a nasty satire? Yes, conditions were bad in the rural South—but could they really be this bad?

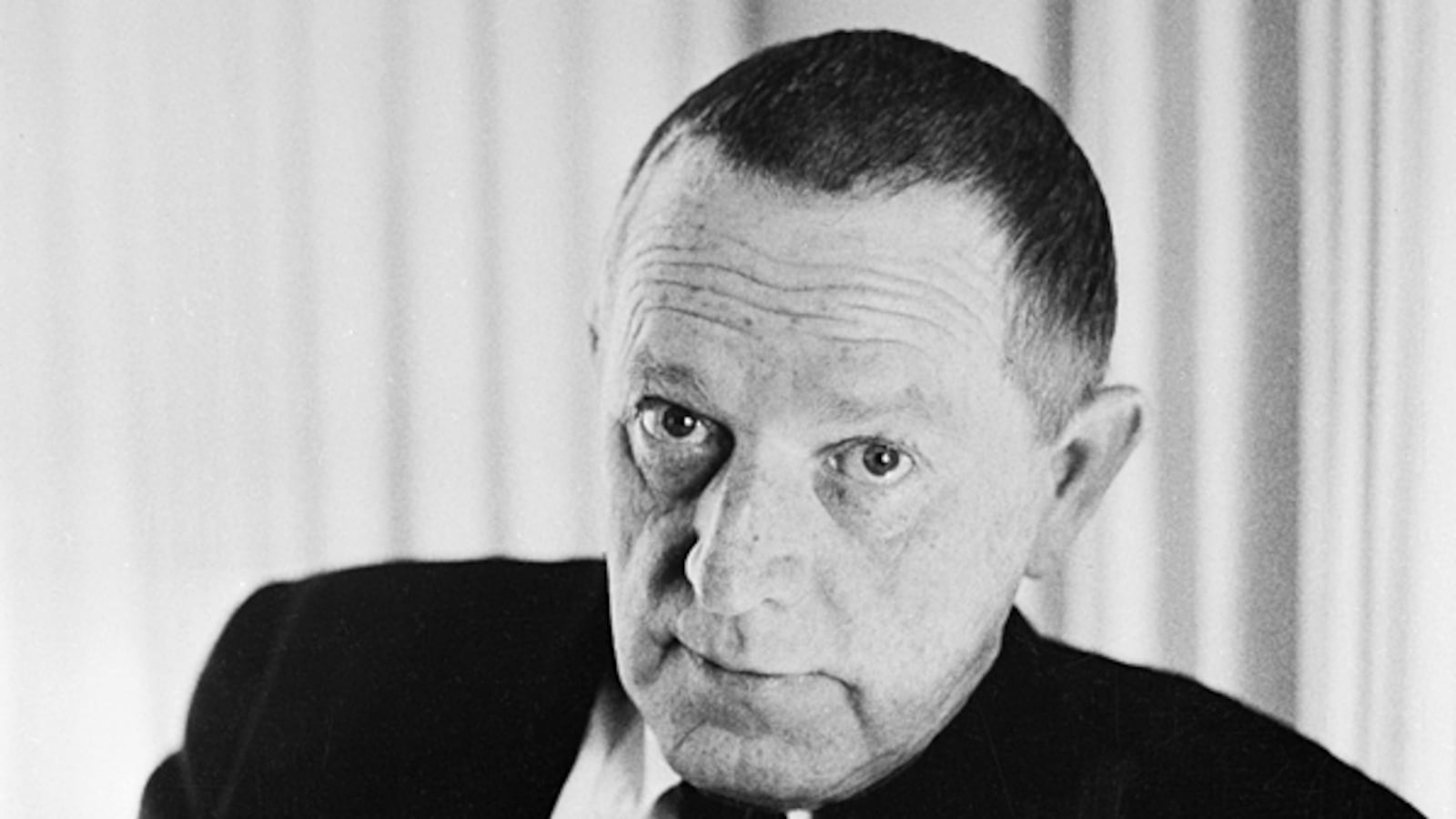

Caldwell, who was severe and defensive in interviews, claimed that he had aimed for both comedy and tragedy:

They’re almost interchangeable, because there is comedy in tragedy and tragedy in comedy. There’s very little distinction between the two; you can’t have one without the other ... You’ve got to be true to your material, and life itself is a series of both. They go right together.

An unimpeachable statement, but disingenuous. Fiction, after all, is not life; the same rules do not apply. Only once in Tobacco Road does Caldwell effectively balance comedy and tragedy, and that is in the opening scene, before the reader is able to grasp the full extent of the novel’s absurdity. The neighbor Lov Bensey, returning from town with a bag of turnips, stops at the Lester property. Lov has a complaint: Pearl, his 12-year-old bride, refuses to sleep with him. He has tried kicking her, pouring water on her, and throwing rocks and sticks at her, but nothing has worked. The only thing left is to tie her to the bed with plow line, but he wants her father to help him do it. But as he is complaining to Jeeter, Lov is distracted by the sight of Ellie May, who is crawling to him half naked across the sandy yard. Soon Lov begins “horsing” with the deformed girl. Seizing the opportunity, Jeeter leaps on the turnips and carries them off into the woods while Ada beats her son-in-law with a stick to prevent him from chasing after.

In this case, at least, the Lesters are motivated by hunger. But greater indignities follow. Dude marries a sexually voracious woman more than twice his age in order to drive her new automobile. When the couple goes into the bedroom to consummate their union, the rest of the Lesters poke their heads through the doorway or drag a ladder up to the window and watch. Jeeter tries to sleep with his daughter-in-law and, it is implied, his daughters. Dude runs a black man off the road, killing him, and only regrets the damage done to the car. Then he runs over his grandmother.

Tobacco Road is grim, but never tragic. Caldwell’s characters lack the dignity of tragic figures—they are too cruel and hateful. The reversals they suffer are not surprising; there is never any doubt that they will end in ruin, in large part because they begin in ruin and show no real desire to escape their fate. For the same reason the novel does not succeed as a comedy. It is funny, but in the way that a tasteless joke is funny: you shouldn’t be laughing, you don’t want to laugh, but you laugh until you’re sick. And when the laughter stops, you wonder whether you’re not so different from a wild animal either.

Other notable novels published in 1932:

Young Lonigan by James T. FarrellLight in August by William Faulkner The Fountain by Charles Morgan Mutiny on the Bounty by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall Mary’s Neck by Booth Tarkington Little House in the Big Woods by Laura Ingalls Wilder

Pulitzer Prize:

The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck (published in 1931)

Bestselling novel of the year:

The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2012. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers.

Previous selections:

1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson1922—Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis