ISTANBUL— A Turkish court freed American pastor Andrew Brunson on Friday, but only after finding him guilty of charges he supposedly spied and helped groups that Turkey regards as terrorists.

The move is likely to ease Turkey’s bitter confrontation with the Trump administration, which imposed import tariffs and treasury sanctions on two Turkish ministers over the case, helping to send the economy here a tailspin.

The court in Aliaga imposed a three year and six week sentence on the Presbyterian minister, aged 50, but suspended all judicial controls and lifted the travel ban, freeing him to leave Turkey. He was quickly on a plane, heading back to the United States.

“We’re grateful to the president, members of Congress and diplomatic leaders who continued to put pressure on Turkey to secure the freedom of Pastor Brunson,” his lawyer, Jay Sekulow, said in a statement. “The fact that he is now on a plane to the United States can only be viewed as a significant victory for Pastor Brunson and his family.”

The chaotic case against the evangelical minister, who’s from Black Mountain, N.C., was based largely on hearsay and circumstantial evidence. It came apart when three witnesses retracted their testimony linking him to terrorist groups. But the state prosecutor nevertheless asked for 10 years imprisonment.

Brunson, who has lived in Turkey for more than two decades, was applying for permanent residence in Izmir, where he was pastor of the Resurrection Church, when he was arrested a little over two years ago.

His detention occurred in the wake of an attempted coup against President Recip Tayyip Erdogan in July 2016. The charges, when they finally came down, related in part to his relations with followers of alleged mastermind Fethullah Gulen, the Muslim cleric living in Pennsylvania’s Pocono Mountains. Brunson was also charged with aiding the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, a banned separatist movement, and its Syrian affiliate, the the Democratic Union Party or PYD.

Erdogan has been seeking Gulen’s extradition for more than two years, but successive U.S. administrations have been reluctant to press judicial authorities, arguing that the Turkish case won’t stand up in court. Erdogan publicly linked Brunson’s prosecution to the Gulen extradition. It appeared to be a hostage situation.

“You have another pastor in your hands,” he said Sept. 28, 2017, referring to Gulen. “Give us that pastor and we will see what we can do in the judiciary to give you this one.”

Brunson’s unjudicial treatment pointed to the political factors in his detention. He was held nine weeks without access to a lawyer or U.S. Embassy contact, highly unorthodox treatment for any detainee in a democracy, let alone the citizen of Turkey’s most important NATO ally. He was taken to prison in December 2016 and held until March 2018 — 18 months after his arrest — before he was charged.

When they did come down, the charges were vague and the indictment a collection of unsubstantiated testimony, hearsay, emails and text messages. They included a novelty, combining the acronyms of two groups on Turkey’s terrorism list – Gulen and his followers (dubbed by Erdogan FETO – the Fethullah Gulen Terror Organization) and the PKK and its Syrian affiliate, the PYD.

The charge read: “While not being a member of the PKK and FETÖ/PYD armed terror organizations, committing a crime in their behalf, and of obtaining, for purposes of political or military espionage, government information that should be kept secret.”

The trial hearings in April, May and July featured mostly secret witnesses speaking over a remote video connection, their voices distorted and their appearances disguised.

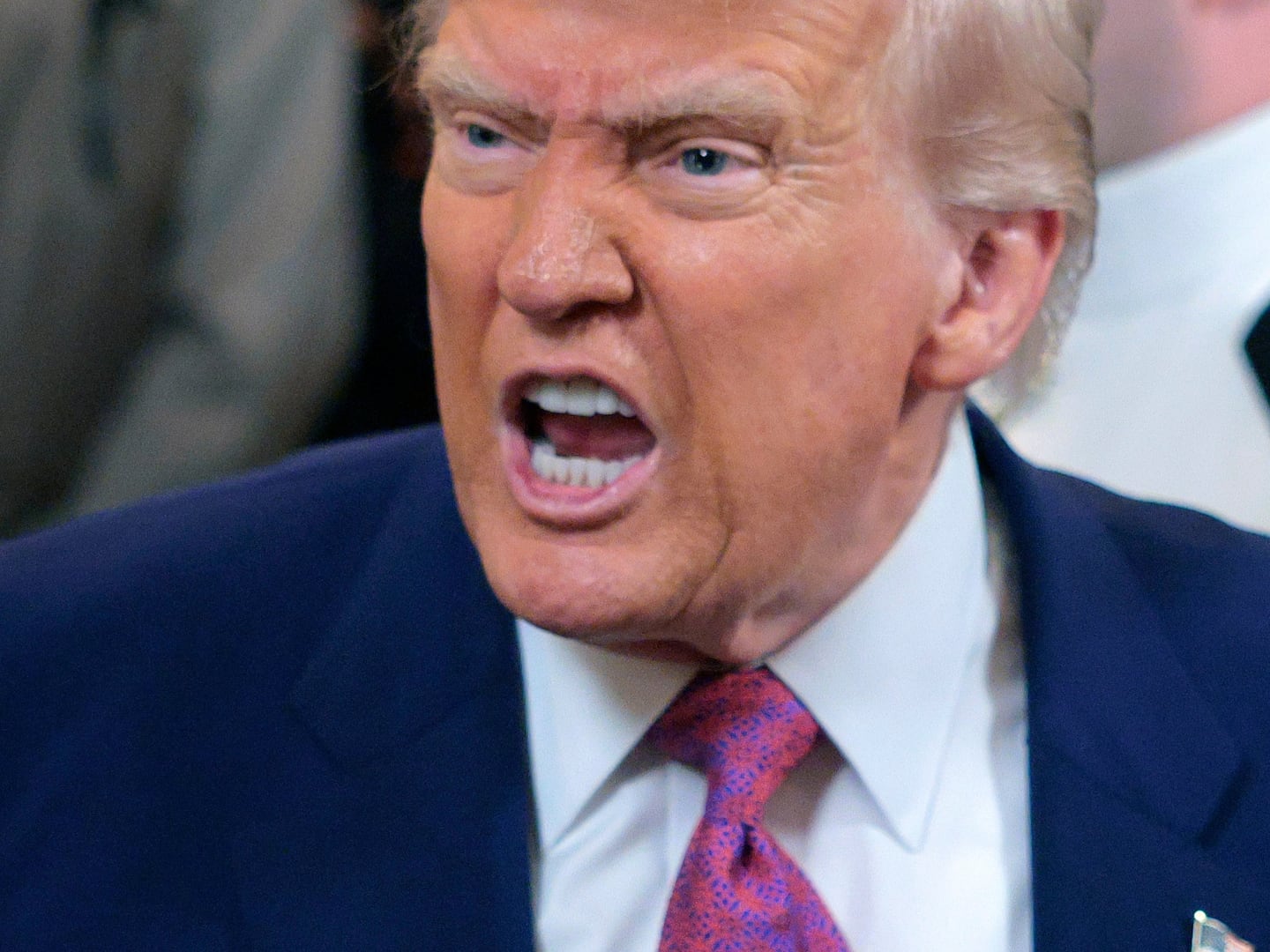

Brunson’s continued detention has been a major thorn in the side of US-Turkish relations, and President Donald Trump, whose base includes evangelical protestant groups, has brought it up repeatedly with Erdogan. Trump thought he’d made a deal with Erdogan at a NATO summit in July, but he conducted his talk with Erdogan with only translators present, and there was an apparent misunderstanding.

Instead of releasing Brunson, the court put him under house arrest. Trump, tweeting that this was a “total disgrace,” later slapped economic sanctions on two ministers and imposed punitive sanctions on Turkish steel and aluminum exports. The Turkish economy suffered a dramatic jolt, the national currency sank on the open markets, and the inflation-plagued economy was in deep trouble.

Turkish officials sent word to the U.S. government that Brunson might be released after today’s hearing, but Erdogan insisted that he would let the judicial process take its course. “I am not in a position to intervene with the judiciary since Turkey is a constitutional state,” he said on Oct. 9. But in the period since the attempted coup, Erdogan has consolidated power over all branches of government and also suppressed free media by arresting journalists.

Brunson’s case is one of many that are under scrutiny for a lack of due process and charges that haven’t been properly adjudicated.

Henri Barkey, a professor at Lehigh University, a leading U.S. critic of Erdogan, offered a scathing appraisal of the Brunson case.

“They manufactured not just evidence but a whole fantastic case with bizarre accusations,” he said in a tweet after the verdict was announced. “They will prove that Turkish justice is nothing but a sham and that almost every other case is just like this one.”

Despite such criticism, the government defended its judiciary as independent and bristled at the notion that the verdict on Brunson was influenced by politics, starting with President Trump’s repeated attempts to pressure Erdogan.

Just 10 minutes after the court handed down its verdict, Trump tweeted: “Working very hard on Pastor Brunson!”

Erdogan was quick to respond, directing his communications director to express “great regret” at “U.S. efforts to mount pressure on Turkey’s independent court system for some time.” Erdogan “has repeatedly stressed that Turkey would not bow down to these threats and noted that there could be no guardianship over the independent and impartial judiciary,” his spokesman, Farettin Altun, said in a statement.

Still, the fact the court in Aliaga didn’t throw the case out after three witnesses recanted their testimony, but imposed a sentence based on a dubious indictment, leaves an image of justice in Turkey that few Turks will boast about.

According to a report in the Hurriyet Daily News, the first witness to recant Friday was Busra Fatma Un, who said she’d never heard that PKK members were treated at a hospital owned by a friend of Brunson and then sent to Syria to fight.

The second witness, who was not identified, said he’d never seen Gulen followers at a prayer house run by Brunson, but had only heard the a rumor to that effect, Hurriyet reported.

And the third witness, also unidentified, withdrew his own claim that a Syrian member of Brunson’s congregation was making bombs for terror attacks, Hurriyet reported.

Updated Friday, Oct. 12th at 1:oo PM ET.