In her bestselling 1997 memoir Prozac Nation, Elizabeth Wurtzel was already expressing concern about the long-term effects of her new antidepressant: “I can’t help feeling that anything that works so effectively, so transformative, has got to be hurting me at another end, maybe sometime further down the road. I can just hear the words inoperable brain cancer being whispered to me by some physician 20 years from now.” But 15 years after Wurtzel’s memoir, Prozac is no longer considered to be so transformative—or even so effective. According to the research of Harvard Medical School’s Irving Kirsch, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the broad category of drugs including Prozac, Zoloft, and Lexapro, are more effective than placebos only in cases of severe depression.

But 10 percent of the American population continues to take them because the message from psychiatrists and from the culture more broadly is, “Why not?”

We still don’t have a conclusive answer about whether antidepressants work, or about their long-term effects. Tentative hypotheses suggest that feedback mechanisms could permanently alter serotonin levels in the brain, but unsurprisingly, pharmaceutical companies are not eager to fund this kind of research. There is also another reason for the startling lack of long-term safety studies: the Federal Drug Administration doesn’t require them. A mere two years of proven safety is sufficient.

Wonder drugs or not, it is now considered culturally acceptable to take SSRIs indefinitely. Psychiatrists often prescribe them without an endpoint, and this attitude toward prescription has changed the way depression is conceptualized. Only two weeks of symptoms are required for a diagnosis, but then—somewhere along the line—depression becomes a lifelong disease that requires lifelong drug treatment. When it comes to therapy, insurance companies are moving in the opposite direction, often paying only for short-term treatment. So we are left wondering: does depression last forever, or can it resolve itself in 20 sessions? Can the drugs do the trick?

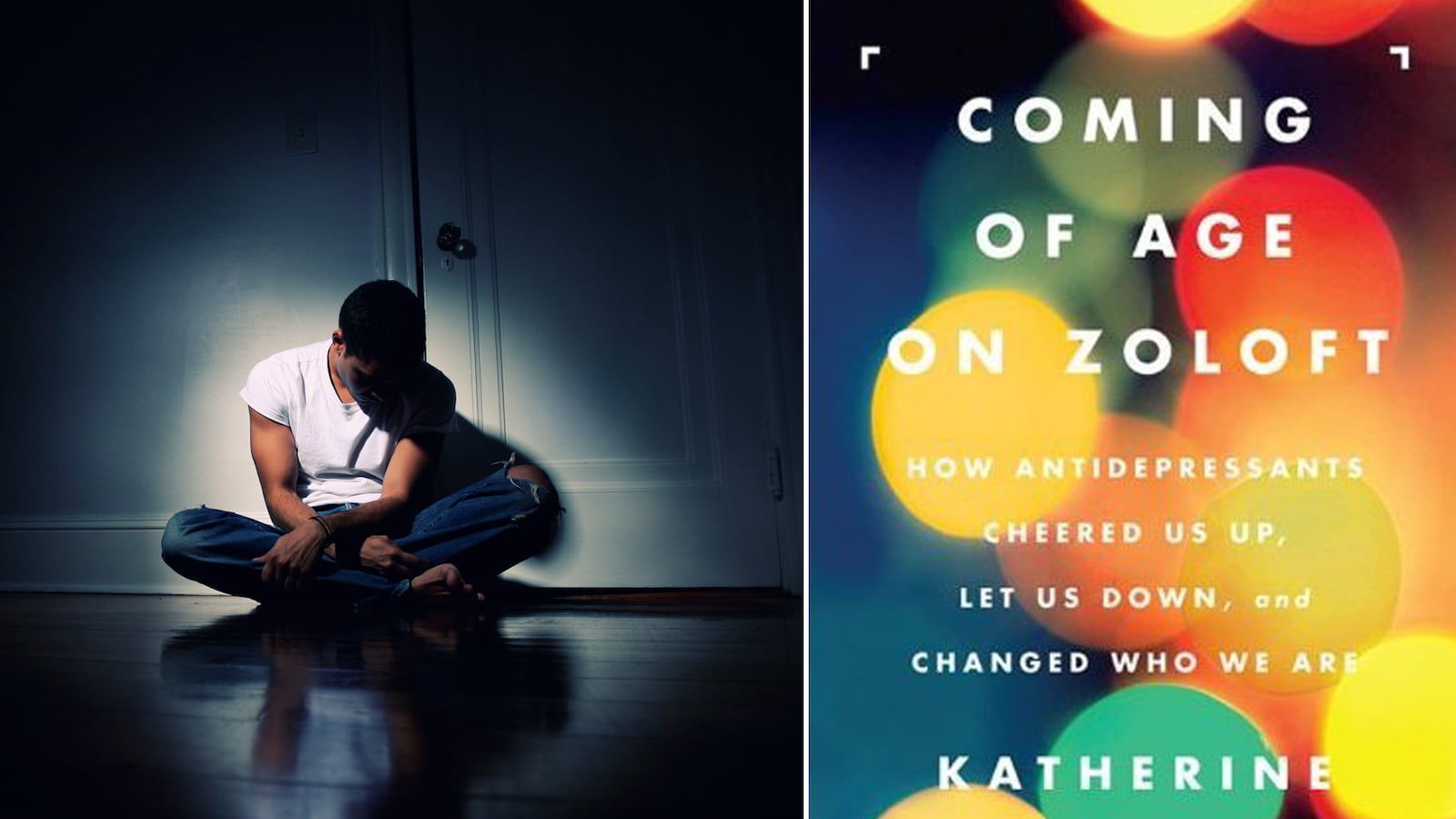

From William Styron’s Darkness Visible to Andrew Solomon’s The Noonday Demon to Wurtzel’s famous memoir, there has been no scarcity of books on depression. But 25 years since the birth of Prozac, we’ve reached that rare moment when it seems possible, and even necessary, to do something new with the genre: to take stock of the experience of a generation that has grown up with antidepressants. In Coming of Age on Zoloft: How Antidepressants Cheered Us Up, Let Us Down, and Changed Who We Are, Katherine Sharpe writes about people like herself: people who have never known a world without SSRIs.

After 20 minutes with a psychiatrist at her college counseling center, Sharpe left with a prescription for an antidepressant, which she continued to take for the next 10 years. Millions of people could say the same, and Sharpe states outright that her own story is neither dramatic nor unique. Rather, its value lies in its similarity to the experiences of so many other young adults born in the 1980s and 1990s.

Instead of a traditional, individual-focused narrative, Coming of Age on Zoloft is a collective memoir, of sorts. Sharpe weaves her own account together with the stories of her peers—a group interpreted quite broadly as anyone from the ages of 18 to 40, but also quite narrowly as white, upper middle class, and highly educated. Most of the book’s subjects are struggling with the same existential questions: Am I a different person on antidepressants? Is life without antidepressants somehow more authentic?

These questions are especially pertinent and confounding when they are asked by people who began taking SSRIs in adolescence. While adults can make an informed decision about whether they want to subscribe to the narrative that SSRIs will restore them to their pre-depression selves, adolescents have not yet fully developed the personalities that could serve as points of comparison. The self on antidepressants becomes the only self they know.

Sharpe intersperses her interviews with a history of antidepressants, placing valuable emphasis on the creation of that narrative of self-restoration and the strategic way pharmaceutical companies have marketed these drugs. “The story of the invention of modern antidepressants and the invention of depression as we know it go hand in hand,” Sharpe explains. There is a widely accepted but never conclusively proven idea that depression is caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain. The rise of this biomedical model of depression was used by “big pharma” to reassure consumers that SSRIs were designed to treat a disease not unlike, say, diabetes. The key date in the story is 1997, when the FDA removed the regulation against direct-to-consumer advertising, making it possible for large numbers of people to go to the doctor specifically to request SSRIs.

The idea of a psychopharmaceutical as a quick fix is nothing new, but the ease with which antidepressants are now prescribed is carrying over into yet another, more troubling class of drugs: atypical antipsychotics, designed to treat diseases like schizophrenia. Sharpe mentions the rise of these drugs as a means of managing childhood behavior problems, but she doesn’t discuss the fact that they are increasingly used in the general population to supplement antidepressants, often with serious side effects.

After 25 years, the chemical treatment of depression may just be getting started. And if SSRIs are changing who we are, we’re still figuring out how.