Scientists have designed a gel that, when injected into a human or animal cell, can conduct electricity like an implant. But unlike traditional electrical implants, their gel doesn’t require invasive and risky surgery to put into place. Additionally, preliminary results show that the body doesn’t reject the bioelectric gel the way it typically reacts to implants.

A team of Swedish researchers published these findings on Feb. 23 in the journal Science. They hope that one day, this technology can usher in a new era of bioelectronics that can help us better understand and even manipulate the human nervous system.

“Our results open up for completely new ways of thinking about biology and electronics,” Hanne Biesman, an organic electronics researcher at Linköping University in Sweden and an author of the new paper, said in a press release. “We still have a range of problems to solve, but this study is a good starting point for future research.”

Though sci-fi sounding, bioelectrics have been used for decades to regulate organs like the brain and heart, Xenofon Strakosas, an organic electronics researcher at Linköping University and co-author of the study, told The Daily Beast. A pacemaker—a small electronic device implanted to correct irregular heartbeats—is a good example of one, as is a vagus nerve stimulator used to prevent seizures in people with epilepsy.

But the problem with these devices and others is that the body’s immune system recognizes them as “invaders.” This can result in the body rejecting the object through harmful inflammation and scar tissue around the implantation site.

Strakosas and his team have been researching softer, more flexible bioelectronics for years to reduce these issues. They decided that an ideal technology was not a solid at all, but rather a gel. Their bioelectronic relies on enzymes naturally found in living cells to activate it so it can conduct electricity.

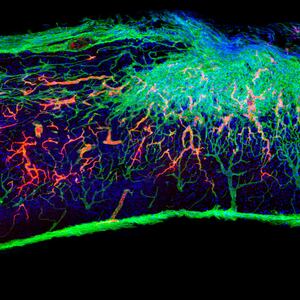

The gel being tested on a fabricated circuit.

Thor Balkhed“By making smart changes to the chemistry, we were able to develop electrodes that were accepted by the brain tissue and immune system,” Roger Olsson, a chemical biology researcher at Lund University who led the research, said in the press release.

The team tested out their injectable gel in the fins, hearts, and brains of living zebrafish to see if their device could be activated in both the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system. The gel was able to conduct electricity and did not harm the living cells where it had been injected. Next, they tried the gel on leeches (used for their large, prominent nerve) and came to the same conclusion: the gel worked, and it didn’t hurt the animal.

In the future, Strakosas said, the team will begin testing the gel on mice. It is not clear yet how often the bioelectric gel might need to be replaced in a living organism, and if it remains harmless as it degrades over time. Injecting a gel into humans would be less invasive than implanting a solid device, and, Strakosas hopes, more effective at addressing humanity’s most difficult diseases.

A less-invasive bioelectric device, for example, could be used for various neurological conditions to monitor a person’s brain waves. Being able to record data over long periods of time could help scientists better understand the inner workings of the brain, and how a disease like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s may alter its function. The same device could also be used to perform therapy—perhaps by strengthening some neural connections or regulating the way that signals are sent.

It’s not just the brain either. The bioelectric gel could be put to use in the spine, heart, or elsewhere in the body to treat conditions involving the peripheral nervous system.

“There are some conditions in the brain that are very difficult to treat with drugs, such as epilepsy, or Parkinson's,” he said. “Bioelectronics are really an alternative solution to try and treat these kinds of conditions.”