“Why do you want to talk about Brian?” Alexis Bloom, the co-director, with Svetlana Zill, of the new documentary Catching Fire: The Story of Anita Pallenberg, asks when I raise the specter of Brian Jones, the ill-fated founder of The Rolling Stones and Pallenberg’s lover during the 60s heyday of the band. “They were young, they were on drugs, he was dazzling, he was a good musician. But he beat her. He beat everyone else. It’s like, she was going to stay around?”

For decades, the “cool kids” amongst Stones fans have fought for what they’ve felt was founder, l’enfant terrible and drug casualty Jones’ rightful place of pride in the history of the band’s rise, while others have wrung their hands over whether it was keyboardist, roadie and founding member Ian Stewart or Brian Epstein protégé and early manager Andrew Loog Oldham who was more deserving of the “6th Stone” moniker.

But maybe they’ve had it wrong all along.

Sure, Jones was a true rebel, suave and committed to the American Blues records the band aped early in their career. And Stewart was likely the soul of the band, who stuck with his friends until his untimely death from a heart attack in 1985, long after the band demoted the founding member who “didn’t fit the band’s image” to road manager at Loog Oldham’s insistence.

Meanwhile, Loog Oldham no doubt catapulted the fledgling Stones into the cultural consciousness with his brilliant Beatles versus Stones marketing gimmicks—pitting his far rougher and less attractive charges against the four guys from Liverpool who had kicked the door open for everyone that followed, feeding headlines to the U.K.’s pre-tabloid press headlines like “would you let your daughter marry a Rolling Stone?”—and helped them shaped their early sound, producing the band’s early records and, according to legend, literally locking Mick Jagger and Keith Richards in the kitchen of the apartment they shared until they wrote some original material.

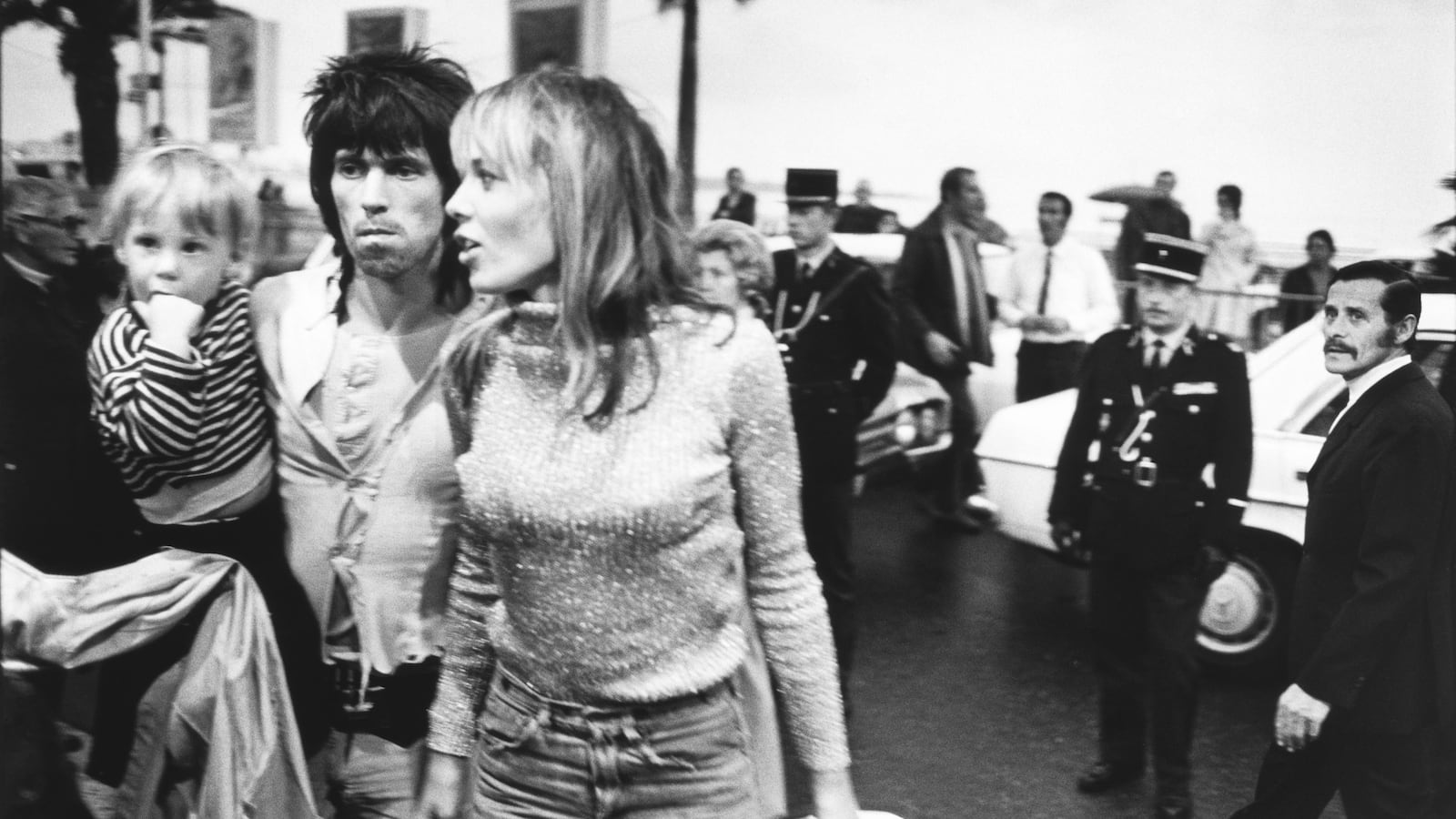

Anita Pallenberg and Brian Jones

Courtesy of Magnolia PicturesSo, all of them are worthy of biographies and memoirs and documentaries—and even tribute concerts and albums—but along the way, the person who helped create the image of The Rolling Stones as we know it today has been overlooked, if not outright forgotten.

Zill and Bloom’s new documentary, out this weekend, aims to rectify that. Catching Fire tells the story of the woman that most fans think of as the London scenestress who hopped from Brian Jones’ bed to a tumultuous, but long-lasting relationship with Keith Richards, introducing bad blood and heroin into what was already a combustible mix. In Zill and Bloom’s telling, culled from the pages of Pallenberg’s unfinished memoir, the first-hand memories of her friends and family—including a remarkably candid Richards—and a wealth of archival film and previously unseen and incredibly intimate home movies and family photos, however, Pallenberg is seen as so much more.

“We set out to make an honest film with the incredible material that gave us insight into Anita’s perspective and this sort of lived experience that is very real,” Zill explains. “So, it’s not a glossy, 2024 version of what we think 1968 was like. It’s what 1968 actually was like. And it was more about leaning into the complicated, three-dimensional person that Anita was. Because she had many great qualities, but she also had a lot of darkness and could be a disruptor, in a good way, but a destroyer, sometimes, in a bad way.”

Along the way, Catching Fire upends the half a century of carefully crafted mythology of what many believe to be the world’s greatest rock ‘n’ roll band, ever.

Continental bon vivant? Style icon? Glamourous cultural touchstone? Elegantly wasted near-casualty? Rock ‘n’ roll pirate with true “I don’t give a fuck” attitude? Yes, that’s Mick and Keith and the rest of the Stones, for sure. But Pallenberg was there first, and if there’s one thing Catching Fire makes plain, it’s that there’s no doubt the band—and most especially Richards—followed her lead at almost every turn.

Anita Pallenberg

Courtesy of Magnolia PicturesAnd so, the beautiful, hedonistic, tortured rebel that Jones became in The Rolling Stones in the mid-sixties, is seen as very much borne of his relationship with Pallenberg. Similarly, Richards’ swashbuckling, rockstar pirate character seems very much a product of Pallenberg’s swaggering personality.

“She was a major influence, no doubt,” says Zill. “Keith is also Keith. But I think Anita had an incredibly strong influence on all of them, and on really everyone around her. She was a very strong personality and a very forceful person, who had this incredible style and incredible taste. But the pirate thing? Yeah, sure.”

“They invented it together,” adds Bloom. “Anita says it in her memoir, with no irony, way before the Johnny Depp days, ‘We were pirates sailing around the world.’ And we were like – you don’t even know the half of it!”

And while the family exerted no control, nor did they meddle as the filmmakers delved deep into Pallenberg’s life, both Zill and Bloom agree that without Keith and Anita’s son Marlon Richards’ support—as well as that of his sister, Angela—the film would not have been possible.

“The first email he wrote to me was like an arrow to the heart,” explains Bloom of Pallenberg and Richards’ first child together. “He’s very articulate and he wrote about Anita in such a deeply profoundly loving way, and also a highly amusing way. Then he said, ‘People always talk about my father, but my mum was the really interesting one.’ That was the hook. So, when I went to meet him in England, he left the pages of the memoir with a note, ‘Here’s the manuscript. Hope it doesn’t give you nightmares like it gave me.’ And it was great, but film is a visual medium, and unless you have footage and photos, you’re left with doing an Anita Pallenberg feature film with actors. But there was just so much archival background to work with, from Marlon and Angela, as well as an inordinate amount of stuff that came from collectors, all over the world.”

Anita Pallenberg

Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures“The Super 8 footage that we got from Marlon was four or five hours of material that was incredible, but also very shaky,” adds Zill. “Keith and Anita were traveling around the world, high on all sorts of substances, and certainly not thinking about holding a shot for very long. So, we mined that footage. And really, there’s gems in that footage, of course. But we leaned into the quality of the atmosphere and the feeling, so it’s like you’re in the moment. This is a film about the experience of living this life. It’s not a film looking back and reflecting on something, so much as trying as much as possible to bring the viewer into the experience of being there.”

As a result, the film isn’t full of talking heads, remembering Pallenberg wistfully. Instead, says Zill, she and Bloom “leaned into the feeling of, ‘I’m in 1969 with them on the road’ or ‘I’m with them in Switzerland in the early seventies.’” And with Pallenberg voiced by Scarlett Johansson, the pair say, it made sense when they interviewed Keith Richards to have it be his voice, but not his face in the present day, so as not to take the viewer out of the experience.

“You want to be with him, in the time period, when he’s in his 20s and 30s, living this experienced life,” Zill says.

Not surprisingly, it’s Richards who steals the show. But it’s a version of Keith Richards that very few of us have ever seen before.

“He was our last interview,” explains Zill. “It took a long time for him to decide to participate in the film, a couple of years. But then, once he decided he was going to do it, he did it, and it was a very unique experience in that it really felt like, ‘Oh, we’re sitting down with somebody who was incredibly important in Anita’s life.’ Yes, it’s Keith Richards, but really, it was her partner. But he doesn’t talk about her. That’s not really something he’s ever done before. He’s done a lot of press, and he’s back out on tour, but his interviews are always about the band and about the music. It’s rarely about his personal life.”

Anita Pallenberg

Courtesy of Michael Cooper / Magnolia PicturesIn the end, Zill and Bloom’s long odyssey in making their love letter to Pallenberg, who died in 2017, led them to truly love their subject, and made her late-life renaissance and sobriety, perhaps, the most inspiring part of her amazing life for the filmmakers.

“Her manuscript was our North Star,” says Zill. “It virtually told us how we were going to build out this story that we were telling, by leaning into what it was she chose to write about and emphasize. And she opened up in the latter part of her life, so that was part of it, too.”

“But definitely, you don’t want to see her just in the context of the Stones,” Bloom adds. “We could have done more with the latter part, in fact. She had this extraordinary revival and very successful personal life. She rode a bike all over London. She went to fashion shows, she went to art shows, she had a gardening allotment, she got back into films, and in fact, we could’ve done a whole film on that period. So, we had to find a way to include it. And that was because she was very much her own person and did have a successful second chapter.”