It’s rare that you find anything controversial to say about a woman who goes to work for a nonpartisan organization that fights sexual violence against women. But Anita Perry is not most women.

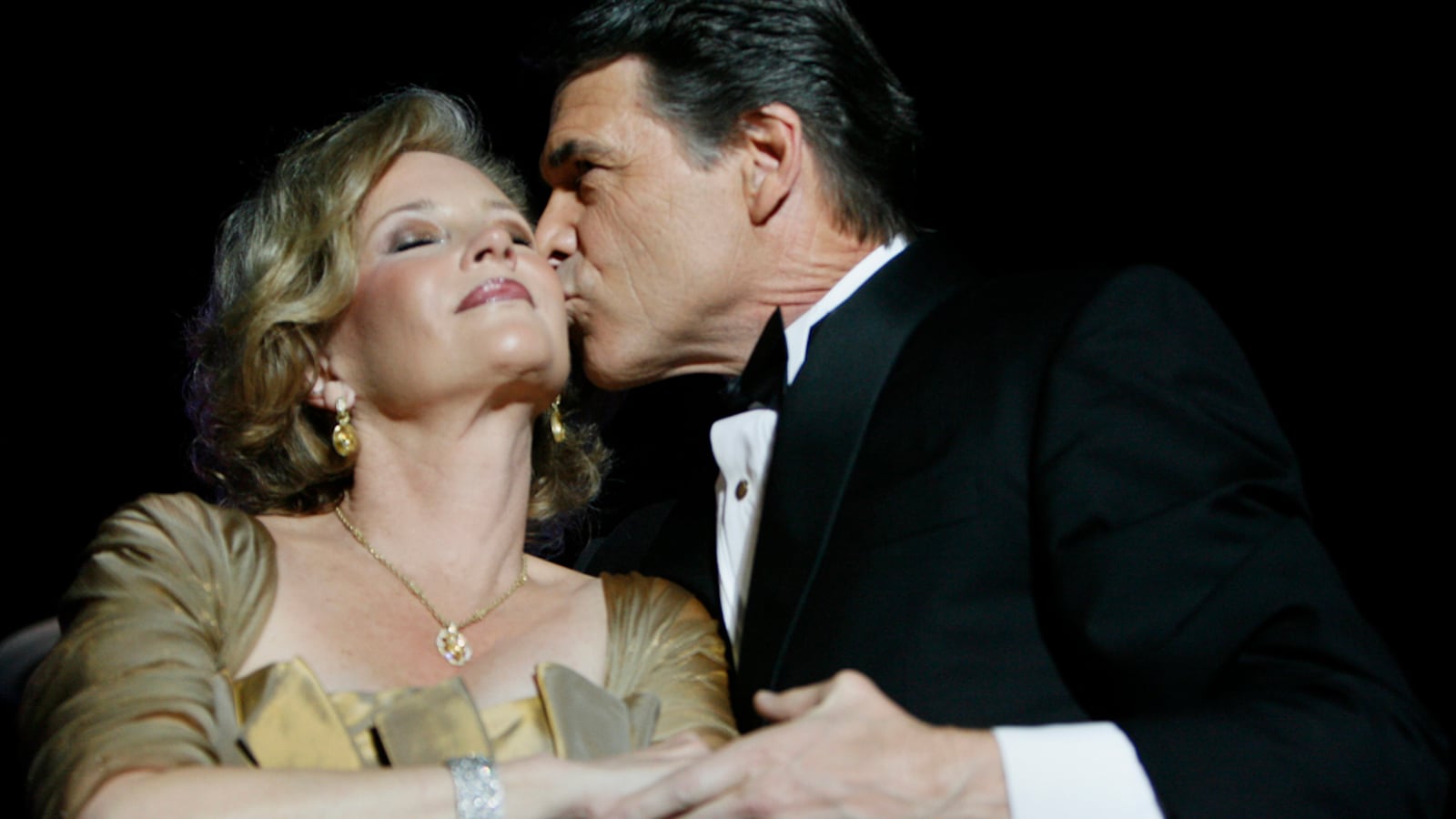

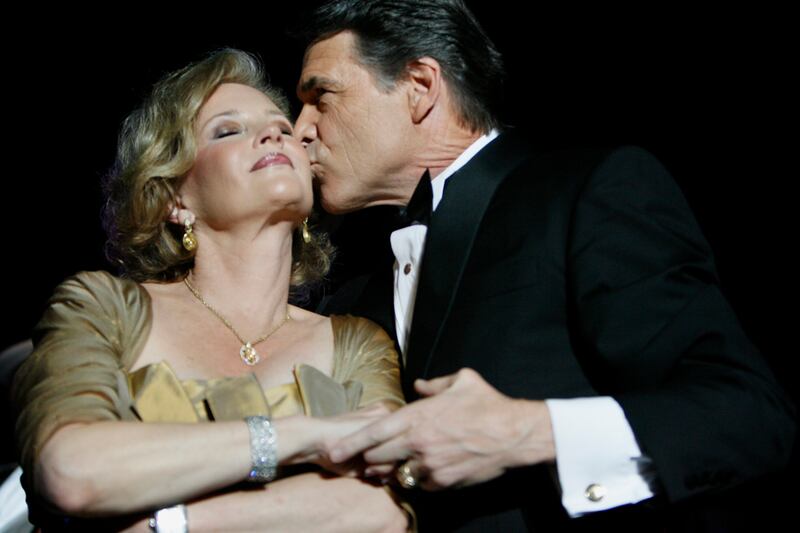

With her husband, Rick, fighting an increasingly nasty and uphill battle for the Republican presidential nomination, Mrs. Perry has become a formidable presence in his campaign: helping open campaign offices, doing town halls with potential voters, and defending her husband after several lackluster performances in the debates. “It’s been a rough month,” the Texas first lady said in a speech at North Greenville University in South Carolina, a Baptist Christian school. “We have been brutalized and beaten up and chewed up in the press. We are being brutalized by our opponents and our own party. So much of that is, I think they look at him, because of his faith.” (The Perrys are evangelical Christians.)

Mrs. Perry is also fending off claims from people who say that her own career amounts to a series of conflicts of interests, in which she and the folks she works with benefit from her association with the governor.

Since 2003, Mrs. Perry has worked for the Texas Association Against Sexual Assault (TAASA), where she’s raised roughly $1.5 million as a $60,000-a-year contract employee during her eight-year association with the organization, Deputy Director Torie Camp tells The Daily Beast.

This summer, a report in the Austin American-Statesman noted that a significant portion of Mrs. Perry’s salary at TAASA comes indirectly from the governor’s “political donors, state contractors, and companies that do business with the state or have issues before the legislature.” Indeed, of 37 major donors to the organization, the paper reported, only three have “no ties to the governor or state business.”

As TAASA sees it, the article in the Statesman was much ado about nothing. “We hired Anita Perry to be a development specialist and fundraiser and she has done exactly that,” Camp tells The Daily Beast. “In my opinion, there would be more of a story if she hadn’t raised $1.5 million and we’d continued to contract her for work. That would be a story.”

Still, if Perry’s campaign picks up steam again, his wife, 59, could find herself vulnerable. As she herself noted while campaigning in Iowa a few weeks back, “We know that every little nook and cranny is going to be examined.”

This last statement extends to questions about Mr. Perry’s sex life, which has been the source of unsubstantiated gossip over the years. In 2004, when some of these rumors reached a fever pitch, Mrs. Perry issued a statement saying, “It's very sad that some people believe that spreading false, vicious and hurtful rumors is acceptable behavior. Rick and I are both outraged that people would drag our family into such ugly, politically motivated nonsense.”

As friends describe her, Mrs. Perry is a good ol’ Southern gal, a stand-by-your-man type, albeit one with a fairly substantial career of her own and a reputation for being a straight shooter.

Born in Haskell County in 1952, Anita Thigpen got her degree in nursing in 1974 from West Texas State University and married Perry in 1982 after a 15-year on-again, off-again courtship that began when the two were in high school. In the early years of her career, she worked in an emergency room and did a significant amount of work with victims of domestic violence and sexual abuse, according to Mica Mosbacher, a prominent Texan and friend of Mrs. Perry’s who’s done work with TAASA. “Sexual assault is an unglamorous kind of charity. It takes a lot to be able to comfort victims,” Mosbacher says. “She’s remarkable.”

After that, while her husband was serving as agriculture commissioner, Mrs. Perry worked for a PR firm called MEM Hubble Communications, where she did health-care consulting for pharmaceuticals like Merck and a local hospital that wound up in a debacle surrounding more than $1 million in allegedly mismanaged funds, according to The Austin Chronicle. When Perry became lieutenant governor, local Democrats wondered aloud whether she wasn’t doing lobbying “on the sly,” serving as a go-between for the firm’s clients and her ascendant husband. “Bullshit,” her old boss Bill Miller said at the time.

Still, Mrs. Perry’s work in the field of health care and women’s issues seems to have had at least some influence on her husband’s views. He supported Hillary Clinton’s 1994 health-care plan. He’s also made appearances at the Texas Conference for Women, an annual event his wife has helped spearhead for the last several years. And in 2007 he took a surprising stand in favor of administering the HPV vaccine to teenagers.

Last month, Michele Bachmann attacked Perry’s position on the HPV issue, saying that his support for the vaccine was nothing more than cronyism that occurred after its manufacturer, Merck, donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to him and the Republican Governors Association, an organization in which Rick Perry has been heavily involved. But Merck wasn’t just a donor to Perry—it was also his wife’s former client from her days at MEM Hubble.

As for Mosbacher, she was approached several years back by Mrs. Perry about doing work with TAASA. The two women went out for a meal, where Mosbacher told Mrs. Perry that she was a sexual-abuse survivor herself and that she would be glad to do work for the organization and tell her story publicly to help raise awareness. Subsequently, she and her late husband, Bob (the secretary of commerce during the first Bush administration), became big supporters and fundraisers for Mr. Perry.

When the Statesman pounced on Mrs. Perry this summer, it also took a swipe at Mosbacher, noting that she and her husband donated $113,000 to Governor Perry’s 2006 reelection campaign. Meanwhile, the Houston Chronicle reported that 155 people who’ve collectively given $6.1 million to Perry’s various gubernatorial campaigns have been rewarded with regentships within the state’s various universities. Among them Mica Mosbacher, who is now a regent at the University of Houston.

Speaking with The Daily Beast, Mosbacher bristles at the notion there’s anything improper about her myriad connections to the Perrys. “I got a nonpaying job as a regent and opened myself and exposed what I thought was a very humiliating sexual assault when I was 20,” she says.

How did everything get so confusing, with friends doubling as political appointees, doubling as spokespeople for the charities of the wives of state officials? The answer is that Texas is one of a handful of states with virtually no campaign-finance laws. Says Andrew Wheat, the research director for Texans for Public Justice, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that formed in 1997 to study political corruption: “Texas has long been the Wild, Wild West when it comes to money and politics. It’s a culture of pay-to-play and crony capitalism deals, and that covers both parties. What puts Rick Perry apart is that he’s been governor longer than anyone in history, so his people are everywhere. He’s built an unparalleled patronage machine. Is it possible somebody seeing this money machine might hire his wife for access to those contacts? Sure. That might be a shrewd strategic move.”

An effort to wrangle an interview from Mrs. Perry was met with radio silence from folks at the Perry campaign, though they have frequently shrugged off complaints of cronyism. In August, when The New York Times wrote a piece about Perry’s complicated ties to his donors, spokesman Mark Miner said, “These issues have been brought up in previous elections to no avail.”