When Annise Parker won her first Houston mayoral race back in 2009, the Houston Chronicle described her as “the first contender in a generation to defeat the hand-picked candidate of Houston’s business establishment” before noting that she would be “the first openly gay person to lead a major U.S. city.”

The New York Times cut right to the chase, with an article that focused on Houston becoming “the largest city in the United States to elect an openly gay mayor” before even noting that mayor-elect’s name.

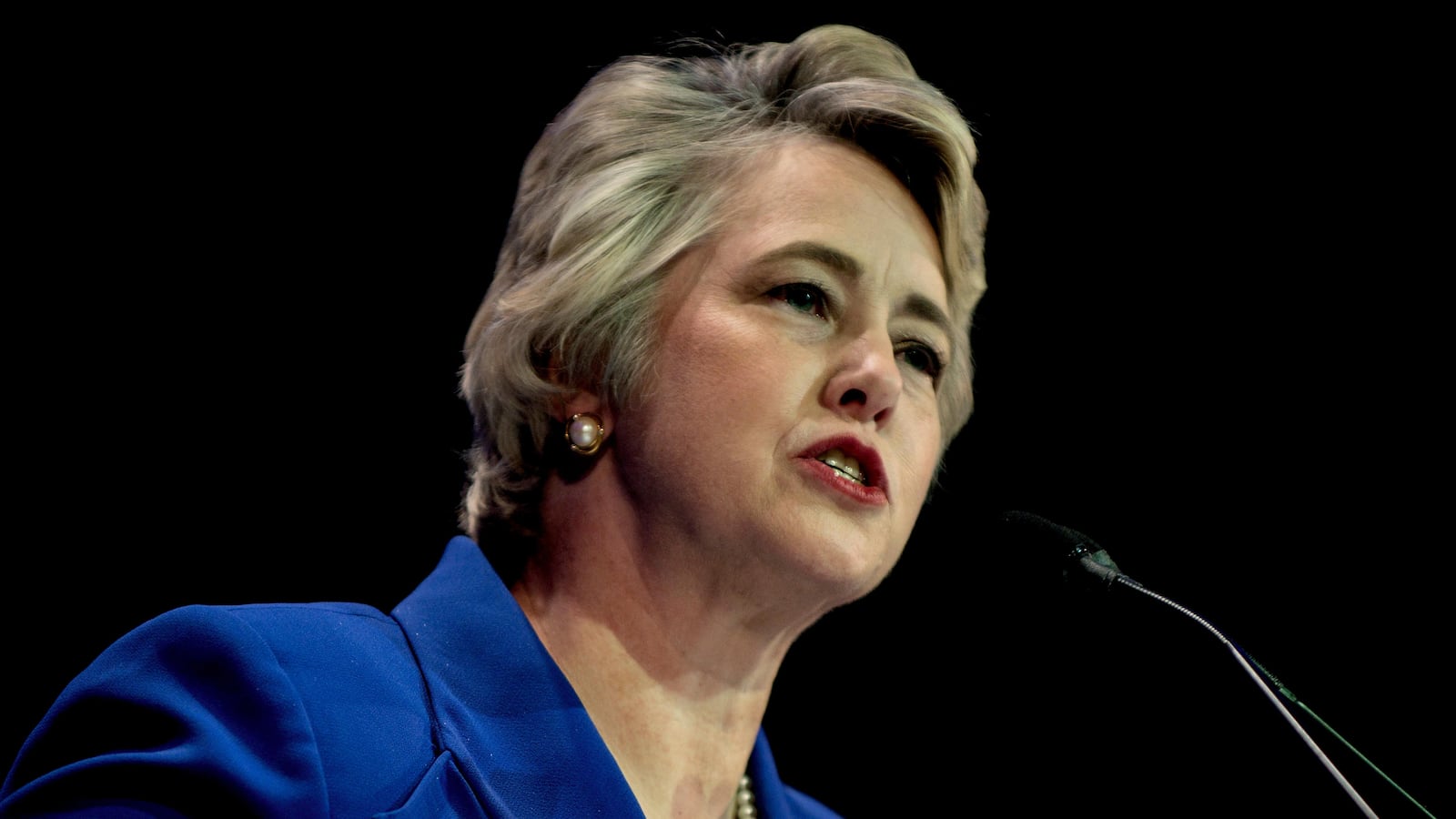

Parker is keenly aware of that difference in coverage as she takes on her new role as the leader of the Victory Fund and the Victory Institute, partner organizations that work to train and elect LGBT candidates for public office.

“The milestones are often what get us coverage—and what get our candidates coverage and attention that they might not otherwise achieve,” Parker, who served as Houston’s mayor from 2010 until 2016, told The Daily Beast in a phone interview about her new position. “What we hope for is fairness in the coverage.”

It’s no secret that the national media is especially drawn to firsts. When Danica Roem, an incoming Democratic delegate in Virginia who is also transgender, displaced the author of an anti-transgender bathroom bill—all while securing a likely spot as the first openly transgender person to be elected and seated in a state legislature—the headlines wrote themselves.

Locally, however, Roem’s campaign primarily focused on the congestion plaguing a local highway.

Much like Roem, Parker is focused on the substance behind the precedent. As the 2018 election cycle fast approaches, Parker—who replaces former Victory Fund president Aisha C. Moodie Mills—will be looking for more candidates like the incoming Virginia delegate, who can simultaneously connect with their communities and boost LGBT political representation on a national scale.

“You’re not a viable candidate if you’re just running to represent the LGBT community or if you’re a single-issue candidate,” Parker said, noting that the Victory Fund seeks “strong candidates who have track records in [their] communities that they can run on.”

Still, as Parker herself remembers, it can be challenging for highly qualified, openly LGBT candidates to shake off the misperception that they are running one-note campaigns.

After spending two decades in the oil and gas industry, Parker ran for Houston city council in 1991 and 1995, losing both times. One recurring frustration for the electoral newcomer was the narrow way in which local papers described her.

“Every time I saw my name in print in both of those two campaigns, it was ‘Annise Parker, gay activist’ or ‘lesbian activist running for city council,’ and that was all anybody could hear,” she recalled. “I’m not at all implying that we don’t need to have candidates who are openly LGBTQ and out there and proud of that—but that’s not what you build a campaign around. And as much as I tried to talk about city issues—bottles and trash pickup, and housing policies and so forth—I couldn’t break through.”

The third time she ran for city council in 1997, Parker told The Daily Beast, she “took a portfolio of the coverage of my previous two races” directly to the Houston media outlets and told them that “gay activist” was not the sum of her identity. The newspaper copy started to shift.

“I don’t know if I was incredibly persuasive or the world had changed—I guess a lit bit of both—but I was no longer ‘Annise Parker, gay’; I was treated like all of the other candidates,” she told The Daily Beast. “Now, they would still figure out a way to say that I was openly gay but it would be after the jump.”

She won that 1997 election, a 2003 city controller race, and then went on to serve three terms as mayor, exiting in 2016 at the end of her term limit.

On a national LGBT scale, Parker is perhaps best remembered for defending the 2014 Houston Equal Rights Ordinacne (HERO), a comprehensive non-discrimination ordinance that was repealed in a 2015 public referendum after a brutally effective anti-transgender campaign—one of the first to popularize the constant drumbeat of “men in women’s bathrooms” that anti-LGBT organizations have been exploiting ever since.

Parker fought to preserve the ordinance at a time when public support for transgender people was not quite as high—nor as loud—as it is today. But there was a perception in the political press that she got “too personal.”

In a long 2015 Washington Post profile of Parker, for instance, Rice University political scientist Robert Stein said that she “made it very personal” and “let her heart, rather than her head, lead us.”

Asked by The Daily Beast if there was still a stigma around openly LGBT elected officials advocating specifically for LGBT rights, Parker said that her only regret with HERO is how much time she spent as mayor before moving forward with HERO—and that she thinks her own identity was not a decisive factor in the outcome of the referendum.

“I would have moved earlier in my administration, but that’s the only difference I would have made,” she said.

Now at the helm of Victory Fund, Parker’s focus is squarely on the future: the 2018 elections. She’s hoping to build on the momentum that’s already in place, with no major plans to shift course. (“More of the same,” she said.) Given that at least 38 Victory-endorsed candidates won their races on Election Night 2017, including several precedent-setting transgender candidates like Roem, more of the same would indeed be a step forward.

But Parker told The Daily Beast that she does have some items on her personal agenda as she takes control of what has become career-making organization for aspiring LGBT politicians: Giving more LGBT people of color the resources they need to run—especially given the fact that 80 percent of the current slate of openly LGBT elected officials are white—and ensuring that the organization maintains a truly nationwide focus.

“I am very committed to making sure that there’s no such thing as ‘flyover country’ for Victory Fund,” she told The Daily Beast. “ I will go anywhere I get invited. We will work to build up our network outside of the major metro areas.”

Recent electoral victories in places like Oklahoma offer proof that traditionally conservative areas of the country are willing to vote for LGBT people. Parker, after all, is a Texan.

“People want to feel that the candidate understands their life and is willing to come to them and engage,” Parker said. “And when we do that, we win everywhere.”