Gathering the threads of a novel is a little like reporting a newspaper story: You start with an idea about the big themes and characters, but what gives it energy are the little bits you stumble upon that make the story tasty and believable.

With my new spy novel, The Increment, I began with the idea of writing about a CIA officer who commits treason by covertly aiding our closest ally, Britain. This subject has interested me for 20 years, ever since I obtained a copy of a secret British study of their covert-action program during 1940 and 1941 to push an isolationist America into World War II. Buy me a drink sometime and I will explain my theory about how the British created the CIA’s predecessor, the OSS, in the image of their own spy service—which is why the CIA has never quite fit the American character.

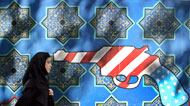

I started with this idea of an American spy who is so worried that we are being pushed into war with Iran that he works with the British to avert that outcome.

ADVERTISEMENT

But I digress: I started with this idea of an American spy who is so worried that we are being pushed into war with Iran that he works with the British to avert that outcome. This CIA officer is anguished by the agency’s failure, and his own, to stop the rush to war in Iraq in 2003, and he is determined not to let it happen again. I know a lot of CIA officers who feel that way, so this character wasn’t hard to sketch.

I gave my character the name Harry Pappas, and if you say, gee, that’s a Greek name—wasn’t George Tenet a Greek?—well, you get an “A” in semiotics. But really, what shaped this character was my own anguish about Iraq: I ended up supporting the war in my columns for The Washington Post, and I wish that I could have some of those columns back. Like Harry, I don’t want to make the same mistake again with Iran.

What focused the novel was Iran itself. I went there for two weeks of reporting in August 2006, and it was the most interesting place I have ever visited. It was a place of light and dark, boisterous in public but intensely secretive, at once joyful and keening: a spy novelist’s dream, in short. I made lots of notes, and brought home street atlases and restaurant menus and all the other cheat sheets that help writers of fiction create a patina of verisimilitude.

And I began thinking about my other main character, a young Iranian nuclear scientist who, for complicated personal reasons, decides that he cannot live anymore as a tool of the Iranian regime—and sends information about his work anonymously to the CIA’s Web site. I’d heard from my sources that these “virtual walk-ins,” as they’re called, are a growing source of intelligence for the agency. And they’re also a huge counterintelligence problem, because it’s hard to know if this anonymous information is real or bogus.

So I thought: What would Harry Pappas do with these over-the-transom nuclear secrets that, to hawks in the White House, provided a “smoking gun” rationale for a military attack on Iran? He would act like a good case officer, surely: He would insist on finding the mysterious Iranian informant and debriefing him—“exfiltrating” him out of the country, if necessary. But he would need help, because the CIA doesn’t have the assets in Iran for such a tricky operation.

And here I found the last piece of my narrative, in the British special-forces capability known as “The Increment.” I’d heard about these operatives a few years ago from American sources who were, frankly, envious that the Brits had such a handy tool for covert missions. The members of The Increment, you see, are drawn from all the nationalities of the former British Empire—Pakistan, India, the Arab world—so they can slip invisibly into countries like Iran, do the dirty work, and get out. They’re described on one Web site as the inheritors of the “007” license to kill. As I imagined them, I formed a raunchy post-imperial, Hanif Kureishi picture: James Bond meets My Beautiful Laundrette.

There were two final strands: A refined London Arab I called Kamal Atwan, who manages a supply chain that feeds the Iranian nuclear program, and a freakish Iranian operative I call Al Majnoun, or “The Crazy One,” whose face has been altered so many times by plastic surgery that it looks like it was put together with a putty knife.

That’s the crew I assembled in The Increment. I may have brought them together, but as is so often the case in writing fiction, they had ideas of their own about what to do. That’s the biggest difference between writing fiction and journalism: When it’s going well, writing fiction is a passive experience, closer to dreaming than deliberate composition.

David Ignatius is a columnist for the Washington Post and the author of seven novels. His book, Body of Lies, was the basis for the movie of the same name directed by Ridley Scott; The Increment has been optioned by Jerry Bruckheimer and Disney.