I hate to be the stick in the mud, but the Obama administration’s announcement of the killing of the radical imam Anwar al-Awlaki, while welcome news, nevertheless raises ethical questions that demand our attention. Awlaki, a top recruiter and planner for al Qaeda on the Arabian Peninsula and among the most wanted terror leaders, was blown to bits, along with several bodyguards, while traveling in northern Yemen.

Awlaki, an American citizen, was unquestionably a dangerous man. The New York Times summarizes neatly: “Mr. Awlaki’s Internet lectures and sermons have been linked to more than a dozen terrorist investigations in the United States, Britain, and Canada. Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan had exchanged emails with Mr. Awlaki before the deadly shooting rampage on Fort Hood, Texas, in 2009. Faisal Shahzad, who tried to set off a car bomb in Times Square in May, 2010, cited Mr. Awlaki as an inspiration.” Others who were inspired, if that is the word, by his online videos, included “the young men who planned to attack Fort Dix, N.J.; and a 21-year-old British student who told the police she stabbed a member of Parliament after watching 100 hours of Awlaki videos.”

Awlaki was reportedly involved in attacks in Yemen as well as in the United States. The Wall Street Journal quotes an administration source as calling Awlaki “a committed terrorist, intent on attacking the United States.” In short, his killing is precisely in line with Obama’s announced policy of eliminating the nation’s enemies before they can strike on our shores, an approach pioneered by his predecessor and greatly expanded over the past two years.

So if Awlaki was such a terrible man, intent on doing such terrible things, what questions could anyone raise about the propriety of what two administrations now have tried to do—keep America safe by blowing up those who would attack us before they can carry out their plans?

Let’s consider two separate problems. Neither is unsolvable, but neither has yet endured the full public discussion that it might in a more noticeable war.

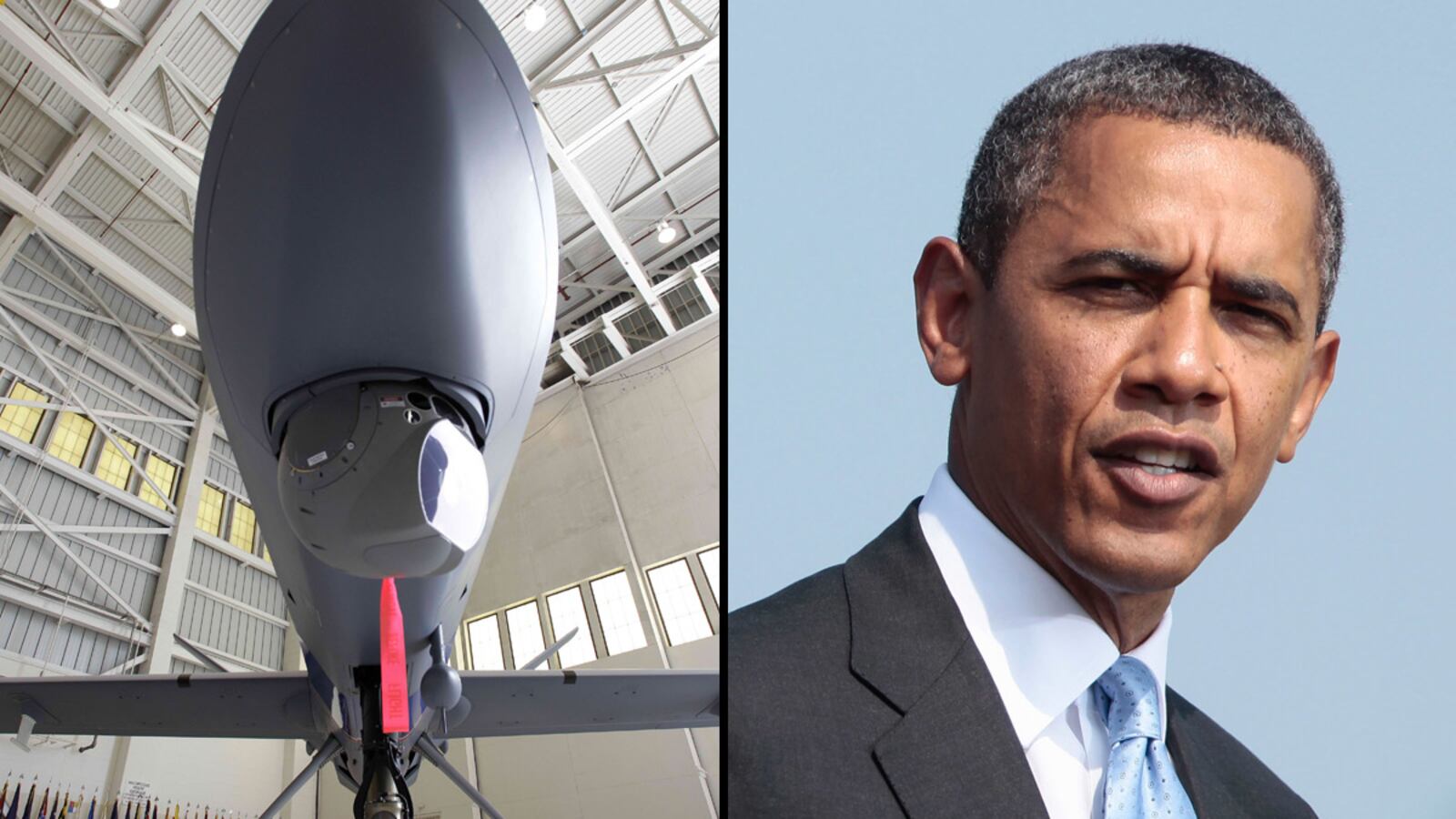

Problem One: What is the source of the president’s authority to order the drone killings? The Obama administration has defended the drone attacks as necessary to the defense of the United States. Many scholars would insist that the commander in chief possesses an inherent constitutional authority to defend the country, but the president’s lawyers have placed their reliance instead on the resolution adopted by the Congress in September 2001 authorizing the president to use force against “nations, organizations, or persons” involved in the 9/11 attacks, “in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States.” What is striking about the resolution is that it mentions no geographic limitations, and the Obama administration seems to acknowledge none.

Why does this matter? Wasn’t Awlaki killed in Yemen? Let’s concede for the sake of argument, although some critics disagree, that a killing in Yemen falls within the terms of the resolution. Is the theater of war to be the entire world? By the logic of the administration’s argument, Awlaki would have been every bit as legitimate a target for killing rather than arrest even had he been found asleep in the grandest hotel in Paris—or Manhattan. In either case, it seems, we would have had the right to blow the building to bits to get him. (I am not saying, and do not believe, that we would have blown either building to bits; only that nothing in the administration’s argument suggests that ordering the hotel’s destruction would have been beyond the president’s authority.) If this is really what the White House is asserting, the American people need to be told, and in clear terms.

Problem Two: What about reciprocity? Under both the law and the ethics governing armed conflicts, sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander. If a tool of warfare is acceptable for one side, then it is acceptable for the other—even if only one of the two sides is fighting in a just cause. And yet I suspect that should a terror group ever use a drone to fire missiles on our shores, we would regard the attack, quite rightly, as a forbidden act of terror, not a legitimate act of war. If I am right in my suspicion, the reason probably is that we instinctively believe that the terrorist is different from other enemies: that unlike an ordinary belligerent, he has no right to fight at all.

Obama seems to have acceded to the view of his predecessor that terrorists are like pirates, whom Cicero famously described as “not included in the number of lawful enemies, but...the common foe of all the world.” One who is “the common foe of all the world”—or hostis humani generis—need not be treated as other prisoners (see Guantanamo detention facility, non-closing of), and, traditionally, could be slain wherever found. The larger point is this: because one who is hostis humani generis cannot lawfully fight, none of his belligerent acts are ever legitimate. That’s why the terror groups would be acting outside the law were they to launch drone attacks of their own, and that’s why we can kill them freely: they have no right to fight at all, even in self-defense. (Indeed, the Obama administration is reportedly preparing to deploy armed drones for use against pirates, too.)

I do not say any of this as criticism of the administration’s growing reliance on remote-controlled drones in the killing of terror leaders. I support the policy. But targeted killing should not rest entirely within the secret discretion of our leaders. The law professor Kenneth Anderson, perhaps the leading academic expert on the legality of drone warfare, has been arguing for some time now that the United States, as the dominant user of drone attacks, should be developing norms to regulate their use. Not rules, says Anderson—he does not envision lawyers standing behind every console operator—but norms, a set of shared ethical understandings to help our leaders decide when the use of targeted killing is necessary and appropriate. I agree.

The right way to develop an ethical sense about the use of drones is through robust public debate. Alas, that task may be difficult, because the drone war tends to slide off the screen. When we have, in the argot, boots on the ground, the public pays keen attention to war, engaging in often spirited argument over rights and wrongs. But the drone war poses little threat to American forces, and the attacks are rarely reported unless some major figure is killed, or a missile goes off course and strikes a wedding.

We should be paying closer attention. The great moral issue in war is the killing, and we are still killing, even when we do it remotely. The drone war may be entirely justified, but that is hardly a reason to stop paying attention. During World War II, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill proposed to his cabinet the targeted killing of the top 150 leaders of the Nazi regime, but agonized over whether the public would accept such an action. By most counts, our drone war has killed hundreds, and probably thousands, and we accept it as a matter of course.

This does not mean that we are callous. Probably we believe in what is being done in our name. Nevertheless, it would be a useful thing for both our country and the world were the president to put aside the reelection battle long enough to address the nation on what he has called the problem of eliminating our enemies. He should tell us, clearly and simply, what the goal of the drone war is; what ethical rules guide him in deciding whom to target; and how we will know when the war is won. Such a presidential speech would treat us as adults—and force us to debate how, and how long, we want to fight.