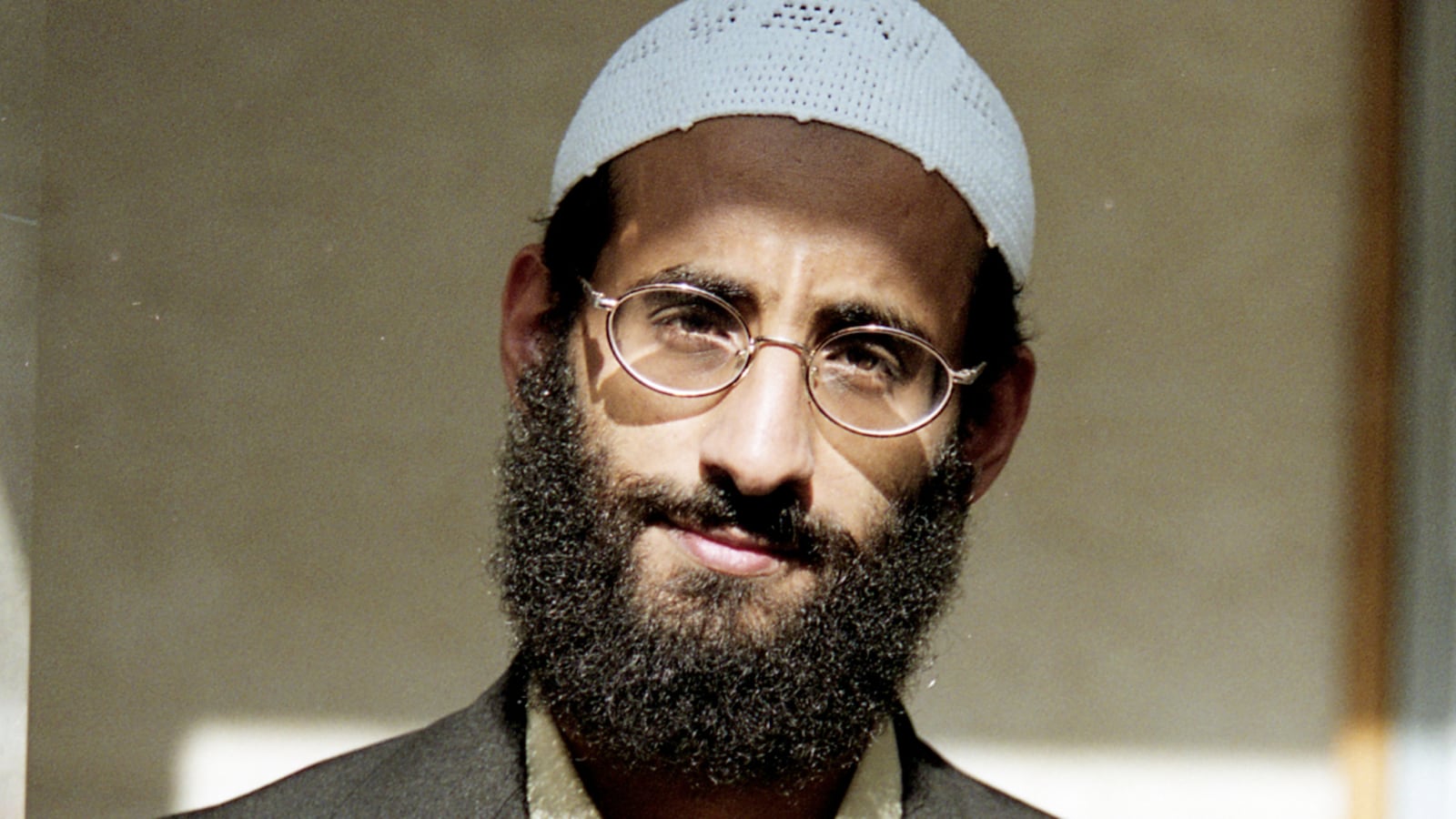

He won't be the last American to declare war on America. Anwar al-Awlaki may be dead, but the United States has produced a generation of jihadi warriors, just as it produced previous generations of 1970s radicals, 1930s red agents, and anarchist bomb throwers with 19th-century roots. Today, with the New Mexico-born Awlaki declared dead in a drone strike, there are still several "Yanks" in the field. Those would include Omar Hammami, a baptized, church-going all-American from Alabama who discovered his Muslim background while visiting Syria. Hammami converted to orthodox Islam, eventually turned into a radical, and has risen within the ranks of Somalia's brutal Shabab militia, currently responsible for the starvation-by-chaos affecting that country.

Other American jihadis include Adam Gadahn, of California, a convert who is now al Qaeda's principle spokesman in Pakistan. Two attacks within the United States were launched by Americans who sought the jihadi path—Faisal Shahzad, who tried to detonate a bomb in Times Square, and the Virginia-born Major Nidal Hasan, who shot 13 dead at Fort Hood in Texas. And there was Samir Khan, killed in the same drone attack that struck Awlaki. Born in Saudi Arabia but raised in North Carolina, Khan was an Internet-savvy propagandist for al Qaeda, and the publisher of the group's English-language magazine Inspire, which struck a bizarrely knowing and ironic tone about jihad, urging potential contributors that when writing about holy war, "Humor is a plus!" The more pathetic and less dangerous examples—Taliban foot soldier John Walker Lindh of northern California comes to mind—indicate how this phenomenon can bubble up from the least expected places.

"They don't see us as we see ourselves," notes former FBI agent Ali Soufan, who spent years interrogating al Qaeda members and worked in Yemen. With clerical credentials and fluent, idiomatic English, Awlaki was a credible candidate to rise, eventually, to succeed bin Laden; along with Ghanan that would have created an All-American dynamic at the top of the group.

Soufan, now a security consultant, describes those recruited to al Qaeda from within the West as "lone wolves," but many of these wolves have sought to move to friendlier climates. At least a dozen Somali-American men have vanished from Minnesota in recent years, believed to have returned to fight in their homeland. It's easier to run with the pack than fight alone.

What many of these American jihadis share is the distance they have traveled, not just physically, but emotionally. Many, like Awlaki, were brought up far from Muslim traditions. Raised until age 7 in the United States, Awlaki did "discover" his Islamic roots during adolescence in Yemen, but when he arrived for college at Colorado State in Fort Collins, Colo., he was, a professor recalls, dressed like all the other American students, a quiet conformist with a reputation as a Muslim liberal. Awlaki's family was hardly sympathetic to radicals—his father, Nasser al-Awlaki, was a professor of agriculture and a technocrat who served the Yemeni government his son attacked. His father "feels a certain degree of allegiance to the United States," says Jameel Jaffer, an ACLU lawyer who traveled to Yemen to meet with the senior Awlaki. "He has a lot of American friends. He lived here a long time….he disagreed strongly with some of his son's declarations and statements." Hardly, then, a cradle of anti-Western sentiment.

But nothing behooves a believer like condemnation—persecution is the mark of success, abandonment the measure of purity. For Awlaki, just as his American citizenship enhanced his authority as a critic of the United States, the denunciation of his own family solidified the distance he had traveled, the sacrifices he made, to become a leader within the organization. American jihadis like Gadahn and Hammami are touted by al Qaeda for exactly this reason—as important messengers precisely because they come from within the beast. "That's their real value to the organization," a senior Western diplomat told me in Yemen, earlier this year. "Their colloquial English, their ability to influence the West."

The Yemeni security analyst Dr. Saeed Ali O. al-Jemli pointed out to me how effective this phenomenon was during the same visit to Sana'a, the country's ancient capital. Awlaki's preaching was itself nothing special, often focused on marital doctrines of Islam and historic interpretations of Koranic verses. Yet this modest American jihadi had a personal narrative of emerging from within the enemy, which allowed him to recruit several hundred followers. Called the "Sons of Shabwa," after the southern town where Awlaki was then preaching, these recruits took a medieval pledge of allegiance not to Yemen's senior al Qaeda figures or the still-living Osama bin Laden, but to Awlaki himself. Bringing hundreds of new fighters into the ranks of the movement increased Awlaki's stature and power. "He's the radical magnet," Jemli said.

This American life—secular, or materialist, or even Christian, in the case of Hammami—embodies and empowers the paradox: you are what you reject. Many of the recruits within Yemen's local branch of al Qaeda are actually Saudi citizens, who fled their own land, rejecting even the official Wahabi doctrines of the Saudi establishment as inadequate. Westerners like Awlaki had even further to journey, making a deeper commitment. The seeds of that journey are planted at home in America, in the easy appeal of radical escapism. Awlaki, who was charged with soliciting prostitutes in both San Diego and the Washington area, apparently had much to prove when it came to his credibility as a Muslim scholar and moralist of self sacrifice. His journey to purity is over, but others will keep marching down that road.