Great Soul, a new biography of Mahatma Gandhi by Joseph Lelyveld, has caused a storm in India by raising the possibility that Gandhi had an intimate relationship with a German-Jewish man named Hermann Kallenbach. Great Soul has been banned in Gandhi’s home state of Gujarat, and has led to calls for a draconian new law against “insulting Gandhi.” This is hardly the first controversy stirred by Gandhi’s sexuality. Every few years, another biography, usually by a foreign author, shines the spotlight on some of the Mahatma’s stranger habits: how, for instance, in his old age, he tested his celibacy by occasionally sleeping beside younger women. Such recurring controversies over his sexuality blur the Mahatma’s real legacy to his fellow Indians: his masculinity.

When I was growing up in a small town in south India in the 1980s, centuries of foreign rule, most recently by the British, had resulted in a crisis of Indian masculinity, which continues to this day. The journalist M.J. Akbar once noted that Indian males grow up in the shadow of powerful women—mothers and grandmothers—with fathers hovering about ineffectually. What was true of Indian society was true of our politics: There were no Charles de Gaulles or Fidel Castros to inspire us. Independent India’s most important statesman, Jawaharlal Nehru, suffered from an air of masculine inadequacy, stemming from his failure to forestall the Chinese invasion of India in 1962. Liberal, tolerant Indian politicians almost always looked like pathetic specimens of masculinity; the charismatic men were either those who had advocated military action against the British—or the even more macho Hindu nationalists.

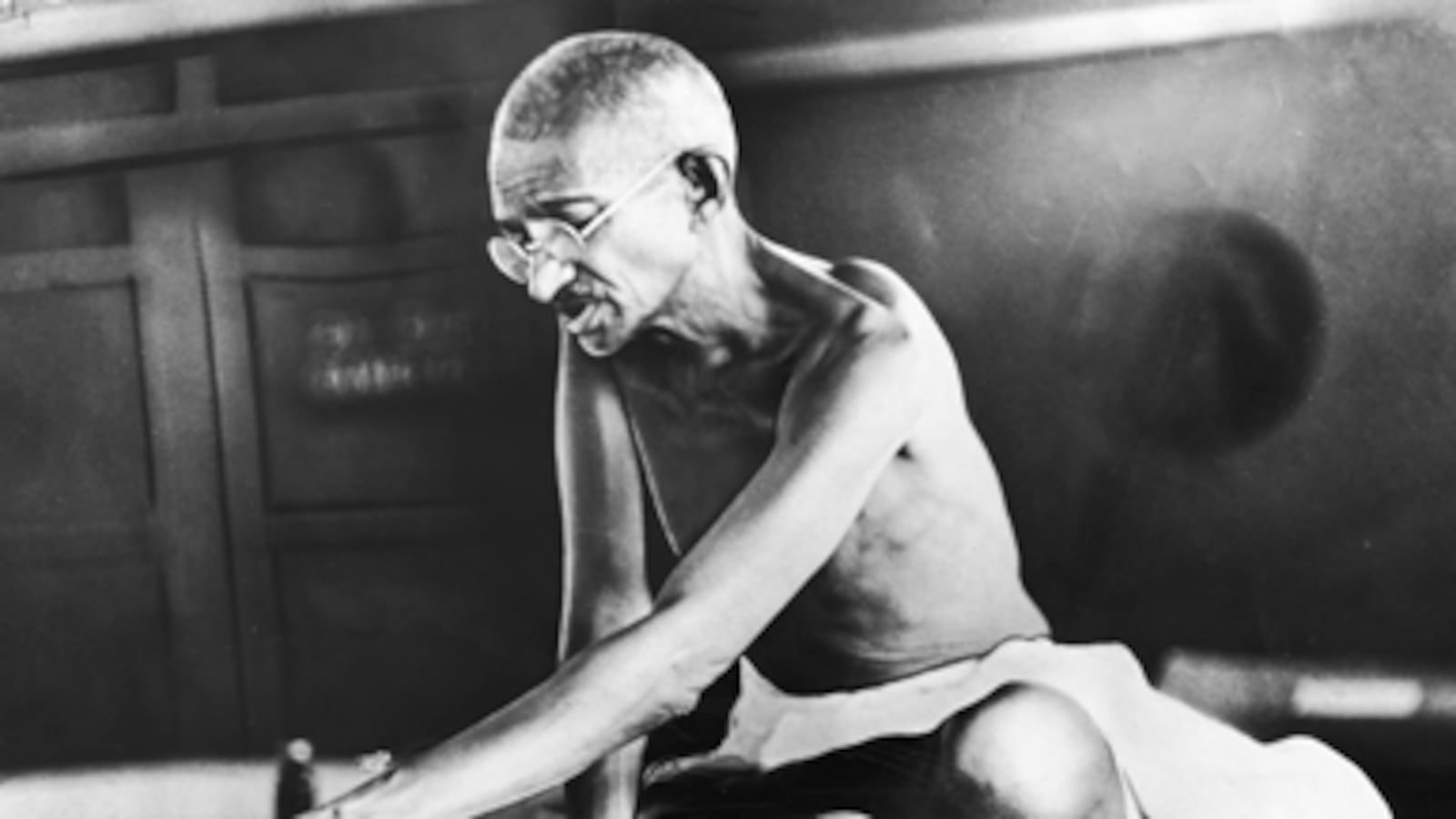

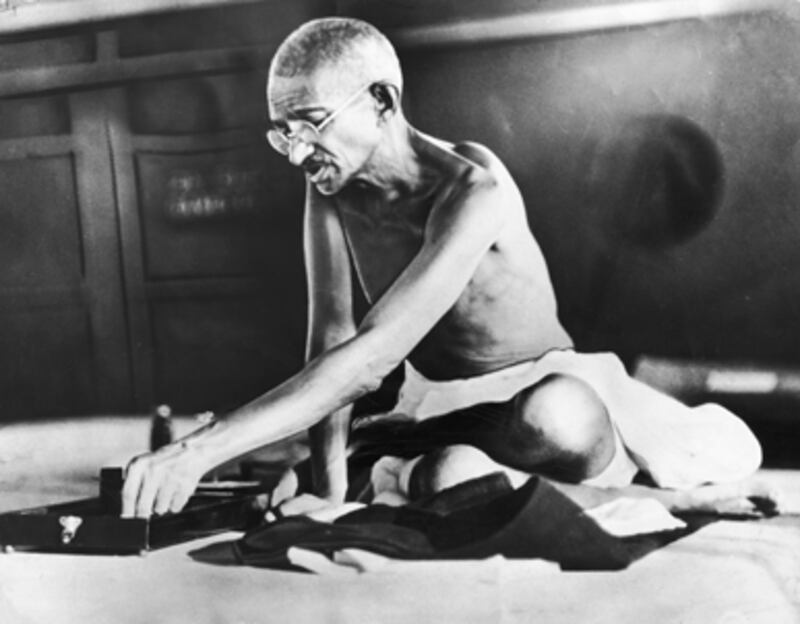

On the other hand, there was Gandhi. He had spoken of peace, nonviolence, and was sympathetic toward Muslims—a sin for which he was assassinated by a Hindu fundamentalist in 1948. Yet he was tough. No one could deny that, not even those who despised him. Look at that lean, fatless body of his, that could apparently go without food for as long as he ordered it to, when fasting for a political cause. This grinning old man with the missing teeth had been sent to jail by the British again and again: but he had never been broken. If this wasn’t manliness, what was?

We in India can never see Gandhi as the sexless, Yoda-like figure that many in the West still do. In his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments With Truth, which is required reading in most Indian schools, Gandhi wrote with candor about his struggles with his sexuality: how, for instance, as a newly-wed man he was so taken by his wife that he shirked his duties to his ailing father to spend more time with her. Honesty of this kind was rare in the ultra-conservative milieu of my adolescence; and Gandhi’s frankness cast a small thin light in between the darkness of small-town sexual taboos on one side, and pornography on the other.

Gandhi is everywhere in India in 2011. Step out of a bus at Majestic, the central bus stop in the city of Bangalore, and you confront a giant poster of a grumpy Mahatma with the message: “Do Not Drink.” This bullying image is the Indian government’s response to the growing problem of alcoholism in the country. Stamped on our currency notes, embossed on government notices, framed on the walls of our police stations, Gandhi’s face is now as an instrument of social control. This is why many young men—and I was one of them—regard Gandhi with something like hatred. On the other hand, in the West, he is just a series of new-age slogans—“Love is peace,” “Truth is everything.” To think of Gandhi as a man—a celibate, virile man—rescues him from those images, alternately bland and repressive, into which he has vanished.

For those of us seeking to understand our masculinity in ethical terms, as a force for good, there is only one model.

For the second half of his life, Mahatma Gandhi was not straight, gay, or bisexual: He was, by choice, celibate. Influenced by the Hindu notion of “brahmacharya” (morally guided celibacy) Gandhi gave up sex in his mid-thirties. In doing so, he was also emulating one of his heroes, Leo Tolstoy, who late in life renounced sex as part of his revolt against the Russian Orthodox Church and the Russian imperial state. Freud’s influence on our thinking is such that we now see all forms of sexual renunciation as repression and neurosis. The world is full of normal, well-adjusted men and women, enjoying normal sex lives: And look what a mess they have made of things. Tolstoy and Gandhi—two very strange men—made it a better place for all of us to live in.

Out of his strangeness came his power. Gandhi the politician—and he saw himself as one—was inventive, cunning, and inspiring. He was also moody, secretive, and egotistical; but what redeems him, what washes away his weakness and weirdness, is his courage. In 1947 and 1948, when his life’s work seemed to have been in vain, and India was being torn apart by sectarian violence, Gandhi did not hide or despair. He walked right into the midst of murderous mobs, chastising them with the simplest of truths: “Thou Shalt Not Kill.”

Young Indian men today can pick from many role models: business tycoons, film stars, cricketing heroes. But for those of us seeking to understand our masculinity in ethical terms, as a force for good, there is only one model. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi is our manhood—our living Indian manhood.

Plus: Check out Book Beast for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Aravind Adiga is the author of The White Tiger, which won the 2008 Man Booker Prize for fiction. His new novel, Last Man in Tower , will be published by Knopf in September.