In his 1971 State of the Union address, President Richard M. Nixon promised Americans that he would begin “an extensive campaign to find a cure for cancer.” He added: “The time has come in America when the same kind of concentrated effort that split the atom and took man to the moon should be turned toward conquering this dread disease.” The idea made perfect sense. We had made so many strides in so many areas of medicine earlier that century, discovering antibiotics to cure infections and vaccines to curb viruses. Surely, ending cancer would be no more difficult.

Our confidence was buoyed by our increased understanding of the links between behavior and disease. Smoking had been established as a cause of lung cancer, raising the possibility that other clear cause-and-effect pathways could be identified. Treatments were improving at the same time. Nearly two in five people who had received a cancer diagnosis were alive five years later, an impressive improvement over the 1930s, when fewer than one in five lasted that long. Promising new therapies for some cancers were on the market, and others were in the pipeline. Optimism was in the air.

More than 40 years after the war on cancer was declared, we have spent billions fighting the good fight. The National Cancer Institute has spent some $90 billion on research and treatment during that time. Some 260 nonprofit organizations in the United States have dedicated themselves to cancer—more than the number established for heart disease, AIDS, Alzheimer’s disease, and stroke combined. Together, these 260 organizations have budgets that top $2.2 billion.

As a result, we know much more about the disease than we once did, but we are not much closer to curing it. From 1975 to 2007, breast cancer rates increased by one third and prostate cancer rates soared by 50 percent. Widespread screening played a significant role in detecting these cases, making direct comparisons difficult. Still we clearly have a problem. Almost 1.6 million people were diagnosed with cancer in 2011. Meanwhile, the rates of certain cancers are rising. An upward trend is especially apparent in kidney, liver, and thyroid cancer and in melanoma and lymphoma. The steady increase in the incidence of childhood leukemia and brain cancer since the mid-1970s is a particularly alarming trend. When have Americans ever waged such a long, drawn-out, and costly war, with no end in sight?

It’s true there have been small declines in some common cancers since the early 1990s, including male lung cancer and colon and rectal cancer in both men and women. And the fall in the cancer death rate—by approximately 1 percent a year since 1990—has been slightly more impressive. Still, that’s hardly cause for celebration. Cancer’s role in one out of every four deaths in this country remains a haunting statistic.

When it comes to treating cancer, we seem to be in a holding pattern. We are still relying on surgery, chemotherapy and other anticancer drugs, and radiation, just as we did 40 years ago. “We are stuck in a paradigm of treatment,” says Ronald Herberman, MD, the former director of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute. And our treatments are not working.

With the “war on cancer,” we may have created a framework that allows us to declare a stalemate, with no expectation of ultimate victory. We may have put generals in charge who think we should start talking about living with cancer as the “new normal.” At least that is what the director of the National Cancer Institute seems to be suggesting when he talks about “making cancer a disease you can live with and go to work with.” Harold Varmus, MD, who has also served as president of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, one of the world’s great cancer hospitals, goes on to say, “We have many, many patients with lethal cancers who are actually feeling pretty good and are working full time and enjoying their families. As long as their symptoms can be kept under control by radiotherapy and drugs that control symptoms and other modalities, we’re doing right by our patients.”

What happened to ending cancer?

Simply put, we have not adequately channeled our scientific know-how, funding, and energy into a full exploration of the one path certain to save lives: prevention. That it should become the ultimate goal of cancer research has been recognized since the war on cancer began. When I look at NCI’s budget request for fiscal year 2012, I’m deeply disappointed, though past experience tells me I shouldn’t be surprised. It is business as usual at the nation’s foremost cancer research establishment. More than $2 billion is requested for basic research into the mechanism and causes of cancer. Another $1.3 billion is requested for treatment. And cancer prevention and control? It gets $232 million altogether. (Remarkably, in the very same budget report, the NCI states, “Much of the progress against cancer in recent decades has stemmed from successes in the areas of prevention and control.”)

The failure to give prevention its due has been a longstanding complaint. Political tensions arose in the 1960s and 1970s between those who wanted more attention placed on preventing cancer by addressing occupational and environmental factors and those who wanted the locus of responsibility to fall more on individual behavior choices. Scholars at UCLA complained in The Journal of the American Medical Association in 1988 that biomedical research, with its clinical and laboratory emphasis, dominated the allocation of federal resources, at the expense of preventive medicine. They called prevention “the most neglected element” of the NCI’s efforts to date.

Decade after decade, similar complaints have been made, and decade after decade, little changes.

It’s true that even with a new commitment in funding and expertise, the prevention of cancer will be a formidable goal. But there are many promising avenues to pursue. It is time to commit our resources to more aggressively studying the ways in which diet, exercise, supplements, environmental exposure, and other factors can influence the development of cancer. It is time to look more diligently for vaccines and prophylactic therapies, and to do a better job distributing the ones we already have.

We also must get the word out about the prevention strategies we know are effective. As recently as March 2012, public health experts told us that we could prevent more than half the cancers that occur in the United States today if we applied the knowledge we already have. Imagine the transformation that could take place if we showed more respect for the powerful and often-subtle strategies of public health—the ones that help people change their behavior, improve access to health care, and regulate environmental and occupational hazards.

We should not “slouch toward a malignant end” and accept cancer as “an inevitability,” as one bestselling history of cancer suggests we do, but instead we need to recognize that the more than $90 billion spent in pursuit of a cure has not achieved the most effective “cure” of all—preventing the disease to begin with.

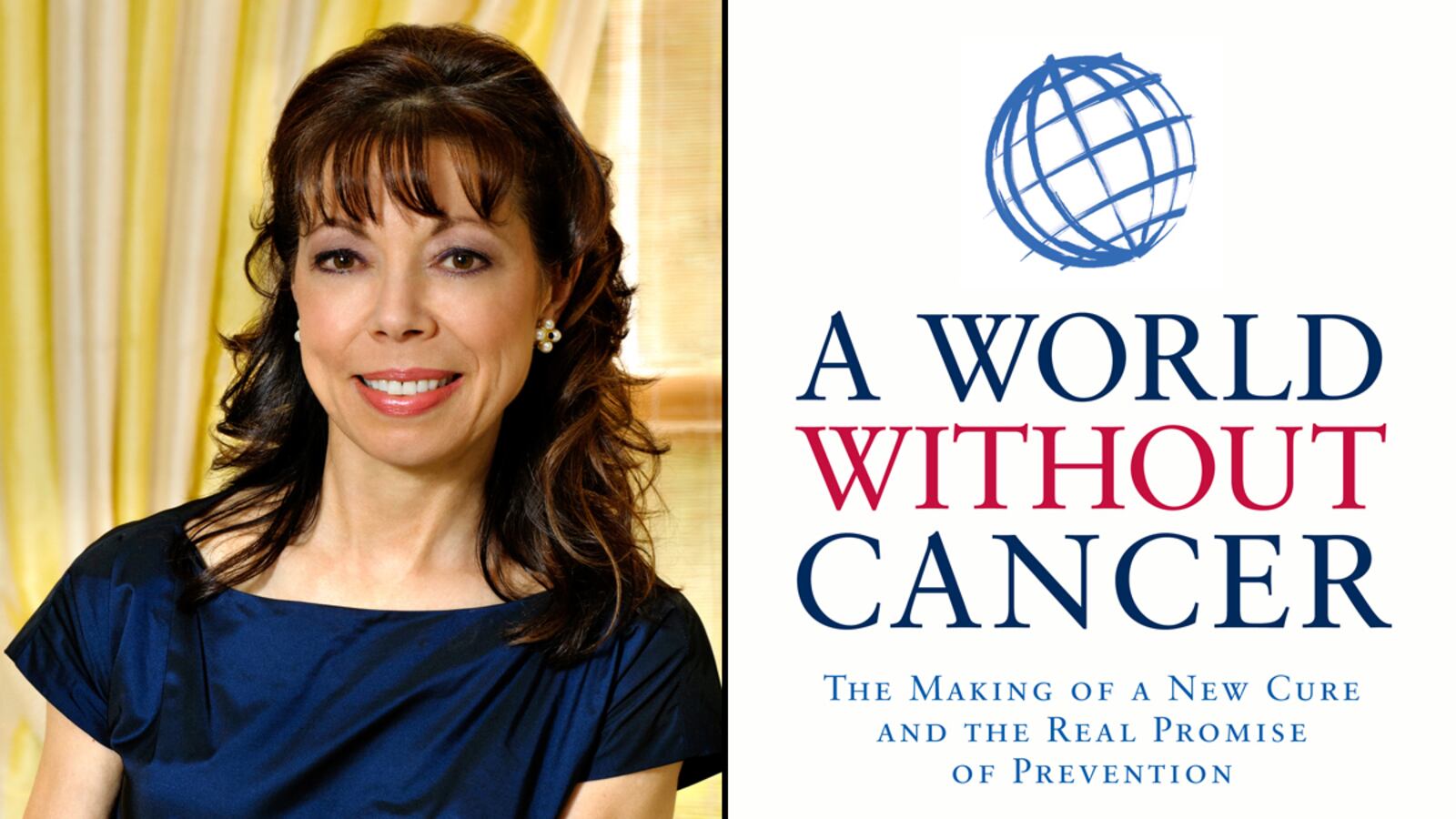

Adapted from A World Without Cancer by Margaret I. Cuomo, MD. Copyright (c) 2012 by Margaret I. Cuomo, MD. By permission of Rodale, Inc. Available wherever books are sold.